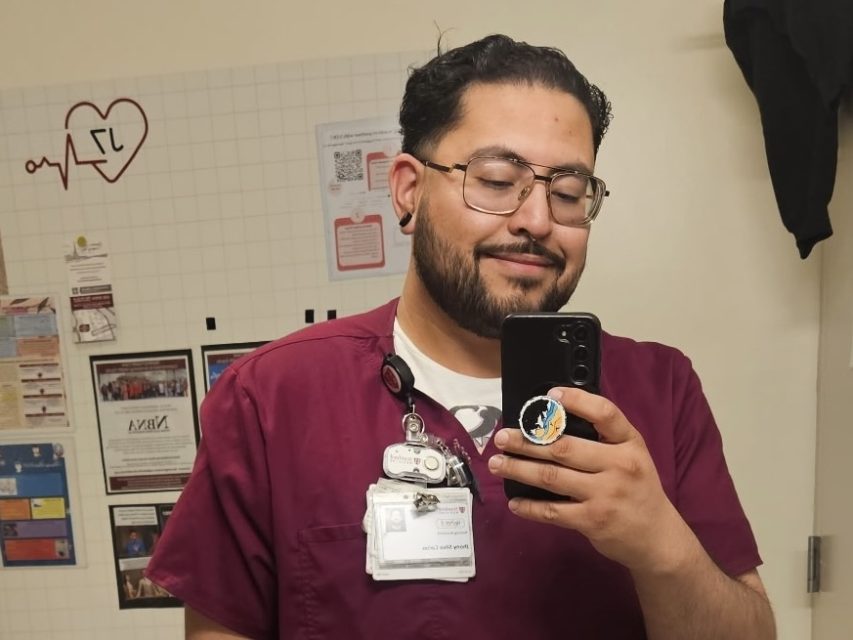

A few weeks ago, Jhony Silva, 29, had a conversation with his child that he never wanted to have.

The 8-year-old listened as Silva explained Temporary Protected Status, and how the Trump administration’s decision to end the program affects Nicaraguans, Nepalis and Hondurans like him.

Silva’s kid still can’t pronounce the president’s name properly, and refers to him as “Donald Truck,” said Silva, who works as a nurse’s assistant at Stanford Hospital’s cardiac unit and arrived in the United States from Honduras more than 25 years ago.

“It’s not very pleasant having to say that I might get deported,” Silva continued. “I don’t even know how to properly explain what being deported is to an 8-year-old, so it’s kind of tough.”

The administration announced the termination of TPS for Hondurans and Nicaraguans on July 7, and set Sept. 8 as the day for the protections to expire. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the decision on Aug. 20. The end of the program affects more than 52,000 Hondurans, 7,000 Nepalis and nearly 3,000 Nicaraguans.

The case remains open with U.S. District Court Judge Trina Thompson in San Francisco, where the next hearing is set for Nov. 18. Depending on the ruling, TPS may or may not be reestablished. If the court sides with the Trump administration, it is possible for the National TPS Alliance to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Silva, who was just 3 when his family came to the United States, is one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit challenging the administration. He has no memory of the Central American nation he could end up being deported to.

While Nepalis lost their status as of Aug. 20, Hondurans and Nicaraguans with TPS lost protections today, Sept. 8, putting them at risk of deportation if they encounter ICE.

Silva arrived in the United States with his mom to meet his dad in the Bay Area after Hurricane Mitch devastated Central America in 1998. Luckily, he said, both his parents were able to get permanent resident status a couple of months ago through his sister, who is an American citizen.

That leaves Silva as the only member of the family at risk of deportation.

“I think my family’s been feeling very guilty,” said Silva. “They feel saddened by the idea of me being the one that’s not going to be able to be here.”

Under TPS, eligible migrants legally live and work in the United States when unsafe conditions prevent those nationals from returning to their home countries. That included the devastation from Hurricane Mitch, which killed 11,000 people, mostly in Honduras and Nicaragua.

In 2015, Nepalis received the protections following an earthquake that killed 9,000 people and destroyed and damaged 600,000 structures.

The designations are usually renewed for periods of six, 12 or 18 months at the discretion of the administration in power.

At present, Silva is also attending Chabot College in Hayward, where he lives. He’s taking prerequisite classes to pursue his dream job to become a registered nurse.

“I love my job. I’ve been chasing after the dream of being an RN for a really long time,” Silva said. “I love interacting with the patients … I’m very grateful to be able to practice my skills, and give patients a good stay at the hospital.”

Silva said that, despite the uncertainty of what might happen to him and the other thousands of TPS beneficiaries, he remains hopeful. He said he planned to return to work, but it was unclear if he would have a job.

“I’m not in this fight by myself. I’m trying my best to stay positive and just try to keep my head down and hopefully everything will work out,” Silva said.

Three of the TPS holders we interviewed for this story, all except Jose Ramos, asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution. We have given each an alias.

Jose Ramos, 28 years in the U.S.

Jose Ramos has already booked his flight back to his home country of Honduras, which he left in 1997.

He had worked as a judge in his hometown of Camasca when changes in the government left him unemployed.

“I had two kids and no way of helping them succeed,” he said in Spanish. He left to pursue more stable economic conditions, leaving behind his wife and children, ages two and seven.

The decision was not an easy one. “When I was here, I regretted it so much. I would cry in silence for having abandoned my kids,” he said.

Ramos worked first as a janitor and later as a carpenter. When he earned his TPS status in 1998, he got a stable job driving trucks for an airport food company. He bought a house, contributed to his Social Security and sent money to his family in Honduras.

“It’s time for me to play my last card, which is to talk to a lawyer and see if I can apply for asylum.” If asylum status looks promising, Ramos will cancel his flight to Honduras.

In spite of his situation, Ramos sees a silver lining in returning to his family after 28 years. “We’ll finally be together, but at the same time, the economic situation [in Honduras] is very complicated.”

‘Juana Perez,‘ 27 years in the U.S.

“Juana Perez,” 49, a Honduran national, came to the United States 27 years ago, just a few months before Hurricane Mitch ravaged Central America.

On hearing the news that TPS would be cancelled, Perez, who worked until last Friday as a nurse’s assistant at Kaiser Permanente in Walnut Creek, said, “I felt like I was gonna pass out. I started feeling so nervous and like my life was being taken away from me. I don’t know how my life is going to be when I don’t have a work permit. It’s really devastating.”

A representative of the Central American Resource Center of Northern California, a Latinx-centered resource group, urged those affected to “look for an organization, a nonprofit or a lawyer that can give you some advice.”

She also recommended talking with trusted loved ones to create an emergency plan in the case of sudden deportation.

After 26 years working in the health industry and the last 23 with Kaiser, Perez’s childhood dream of helping people came to an abrupt end after the Ninth Circuit upheld the federal government’s decision on TPS.

Her benefits officially came to an end today, Sept. 8.

“I haven’t slept. I haven’t eaten, because my appetite went away,” Perez said during a phone interview on Aug. 27. “I feel like that part of my body is not with me anymore, like I lost part of my life.”

Perez bought a house in Concord four years ago, and is the caregiver for her 85-year-old mother. Now, with no work permit and her future in limbo, she worries about her mortgage payments and the health of her mother.

Perez’s mother became a U.S. resident through her son, Perez’s brother, who became a citizen after marrying a U.S. citizen.

Perez also has a daughter who lives in San Francisco, who became a U.S. resident after marrying a U.S. citizen following years of living in the country with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals benefits.

As a permanent resident, Perez’s daughter is unable to sponsor Perez. For that, Perez’s daughter must become a U.S. citizen. She won’t be able to apply for citizenship for two to three more years. Once she is a citizen, the process of sponsoring Perez could take between 13 and 15 months.

In the meantime, Perez prays that a November hearing can bring her life back.

‘Elena Lopez,’ 32 years in the U.S.

“Elena Lopez,” 62, left Honduras after her husband abused her. She fled him and, one by one, brought her seven children to the United States.

Like Ramos, Lopez hopes to receive asylum to continue working in the U.S., but regardless of the outcome, returning to Honduras is not an option.

“I wouldn’t leave with my entire family still here. I already have two grandchildren. I’m, as one might say, ‘rooted’ here,” she said in Spanish.

TPS allowed Lopez to earn a living as a union janitor for 12 years. In 2024, her status allowed her to legally travel to Honduras and visit her sick mother in the hospital before she died.

Upon arriving, she saw the dire economic situation firsthand. “To simply get an injection at the hospital, you have to buy the syringe yourself.”

In 2022, Lopez suffered an accident at work where she fractured her finger and injured her back, leaving her disabled and unable to work. She receives workers’ compensation and financial support from her children.

In Honduras, given her age, Lopez would have trouble finding work at all. “For one hour of work over there, you get paid 12 lempiras, not dollars.” Twelve Honduran lempiras are worth less than 50 cents.

‘Diego Cruz,’ 29 years in the U.S.

“Diego Cruz,” 53, has been here since 1996. He first landed a job as a hotel janitor when, in 1999, he was granted TPS, and later transferred to a different hotel where he’s worked ever since.

Cruz established himself in Richmond where he saved up to buy a house. He met his wife here, who is from El Salvador, and they share two U.S.-born children.

When he learned that his TPS status would be revoked, he felt defeated. “I had low self-esteem. I couldn’t sleep,” Cruz said in Spanish. “I’m still thinking about it: ‘What am I going to do?’”

His employment through TPS allows him to send money to his mother in Honduras, who suffers from Alzheimer’s. It also offers him health insurance, which allows him to access medication for a brain tumor that had to be surgically removed in 2002.

Deportation to Honduras would be a death sentence. “I can’t survive without medication. The doctors already told me.”

Cruz also mentions that TPS has allowed him enough financial relief to support his children, 15 and 16, in their pursuits. “They like soccer. I take them [to games and practices] and I got my driver’s license [to do so].”

For now, his plan is to stay here and try to work. “My hope is to be able to see my kids grow up, and maybe I’ll get another chance later.”

I’m just Speechless reading about these people who may have to up root the life they have build here in the pass 24 to 32 yrs. This deportation could have been done in a more humanity way . People are being up rooted from school, colleges and decent jobs. This madness has to end. It’s very important to vote right! When a person shows you who they are. BELIEVE THEM!

the point for people who believe others are less than human is to treat them as less than human because they need to convince themselves and everyone else that it’s ok to do so. the more they normalize the inhumane treatment, the easier it becomes to believe that they are superior and that others who are somehow different from them are less deserving of being treated as equals. this was the way colonizers treated indigenous people they conquered, the way slavers treated those they enslaved, and the way abusers control and dominated their victims of domestic violence along with so many other situations where violence or the threat of violence is used to make people with less power follow the orders of those who believe it is their right to take away other’s rights. The scary part is how most people want to just stay on the sidelines saying “it’s not my problem” up until the point it affects them directly at which point it’s usually too late. then they look around for help and see others doing the same thing of turning a blind eye to the injustice. until a huge majority of us begin to take on injustice to one as an injustice to all and stop these attacks on the people of this country, we will continue to see things get worse because that is how all atrocities develop. It hardly ever starts out the worst from the beginning, it’s only getting started. will you speak out before its too late?

Republicans and urbanist yuppies don’t actually care about brown peoples’ problems.

This shit is evil no matter what they say, drastic non violent actions are warranted. Strike, or…?

You mean to tell me Temporary Protected Status isn’t permanent??? Who could have known it’s only temporary?

I don’t know why I wanna comment on this!!! all the 70 the focus on immigration. I guess a new way to get money start a nonprofit because I ain’t haven’t heard not one. Take these people that you’re fighting for. Take them to your house. Take them home. You’re not gonna do that not at all, but no one has talked about the Homeless situation the American people that living in this country that needs help. Disregard that disregard what’s going on in America!!!

Good. Deport every single one of these leeches on society. They drive up our rents they drive down our wages and they fill up our emergency rooms and they make Medi-Cal care impossible to get by American citizens. Deport every single line cutter.

They literally pay into that system with their income tax. These are healthcare workers and people caring for our society. If anything American citizens are the leeches, sucking these people dry while they have no protections from our greed.

Seeing how many racists we have in this city makes me sad. Just disgusting.

It’s nice to see how they all have money to buy houses and send back home to their countries. Must be nice! They probably should have spent some of it on an attorney to be here legally. Once they are gone back home with all the money they’ve made in this country, their houses should be donated to homeless American veterans. Now the jobs, education, and healthcare they have stolen will be open to needy citizens and/or legal residents. That seems fair.

It’s very sad that the richest 1% of our society has convinced you that it is the poorest and most vulnerable people who are stealing from you, not the greedy billionaires with their 15 vacation homes and private jets.

The ” no kings” rally was principally sponsored by Walmart heiress Christie Walton. You’re the one who’s working for the billionaires.

https://www.wsj.com/politics/a-walmart-heiress-breaks-ranks-and-joins-the-anti-trump-movement-b4395841

In the US for all those years…on Temporary Status…and never applied for a green card to work at getting citizenship.

These are very very sad stories but what were those people doing for 20 and 30 years – while family members around them were go through the process?

Not everyone qualifies. It can be get difficult and require lots of funds to be able to navigate that process.

So if you don’t qualify for legal status and citizenship……we should let you stay????

Maybe because these immigrants are working hard caring for our kids and our elderly and building our homes and we are not racists who have no empathy or intelligence?