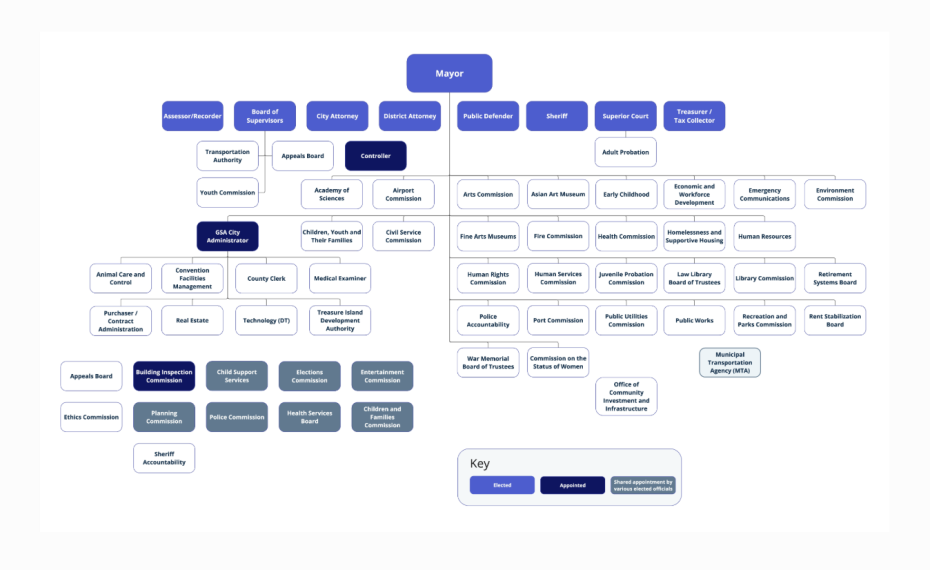

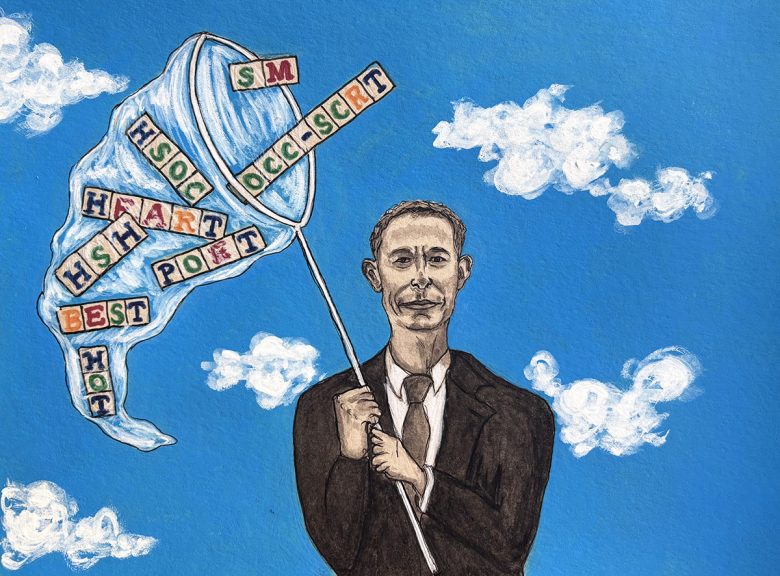

For years, San Francisco has had a near cottage industry in creating new teams and departments for confronting homelessness, addiction and the mental health crisis on the city’s streets.

Workers from HSH, HSOC, HEART, HOT, BEST, POET, SM, OCC-SCRT, and others have been dispatched to help those in need on San Francisco’s streets.

It’s a mess of acronyms nearly as confounding as the alphabet soup of government agencies that DOGE (itself, inevitably, an acronym) has targeted.

It’s no surprise that an incoming mayor with no government experience might be dumbfounded.

What’s more, when Mayor Daniel Lurie walked through the Tenderloin or the Mission, he discovered that tending to someone sprawled on the street often required calling up workers from several of those acronyms — preferably in the right order — so that the person could get a wound tended to, a prescription filled and, possibly, a shelter bed.

Marshaling all of those workers in a timely manner, though, was no easy task.

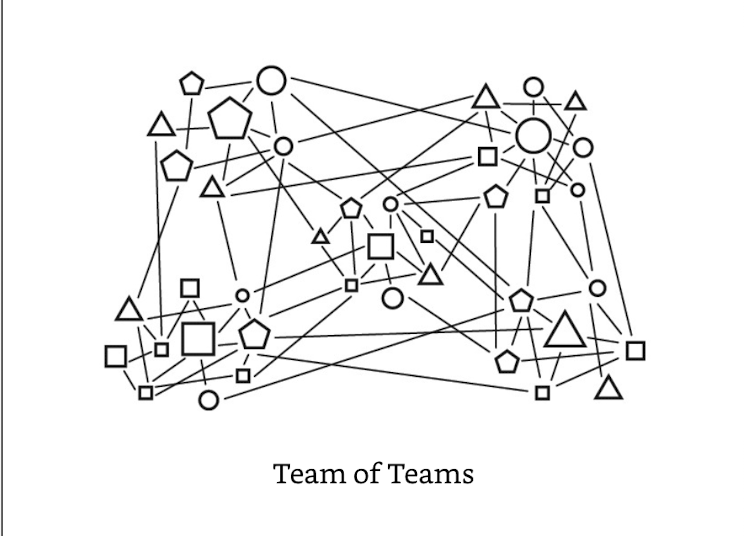

Being effective in today’s world is less a question of optimizing for a known (and relatively stable) set of variables than responsiveness to a constantly shifting environment.

Stanley McChristyal in ‘team of teams’

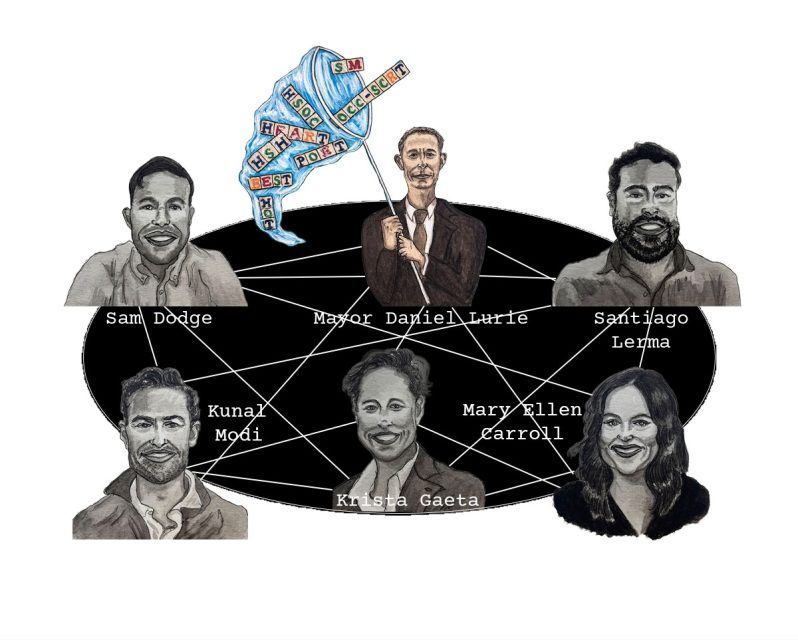

Lurie wanted simplicity. A group of professionals who had been working on the city’s homelessness problem for years noticed this in his campaign literature and, as one of them said, “leaned into it.”

In early January, Sam Dodge sent a memo to Lurie outlining how the many street outreach teams could be consolidated. City workers had long known that coordination between street teams was a problem so, in 2022, Dodge was hired by the Department of Emergency Management as manager of street response coordination.

In his memo, Dodge suggested creating one team for addressing homelessness and keeping the streets clean and another team for addressing medical concerns, including mental health and drug use.

“These proposed changes will enable the city to allocate resources more effectively, improve outcomes, and foster stronger connections between city departments, teams, and the communities they serve,” Dodge wrote.

But, how to actually undertake this consolidation was far from simple. Seven city departments had workers providing a wide variety of services, including addiction treatment, cleaning the streets, shelter access, medical treatment, psychiatric help, and more.

Each of those departments then had its own long list of funding sources, as well as contractual obligations, philosophies and internal culture.

The city’s structure looked not unlike the top-down command structure in the military, or one in a large corporate enterprise, or City Hall.

Enter Kunal Modi. Lurie’s new policy chief of health and human services. He was appointed on Jan. 7, and possesses a background that includes government efficiency consulting for McKinsey & Company and serving on the boards of homelessness organization Larkin Street Youth Services and social service nonprofit St. Anthony’s Foundation.

Over the next few months, the overriding principle shifted to the approach popularized by former U.S. Army General Stanley McChrystal in “Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World,” according to Modi.

Drawing on his experience leading the Joint Special Operations Task Force during the Iraq War, McChrystal argues that most bureaucracies, including city governments, have siloed people with different skills in separate departments, making it difficult to solve complex problems.

Instead, organizations should create teams of people with different specialities and task them with a common goal.

Dealing with complex problems, McChrystal argues, requires a team of teams, where “teams that had traditionally resided in separate silos would now have to become fused to one another via trust and purpose.”

Over the next few months, the transition team helped create a new system for addressing street conditions in collaboration with city workers with years of experience working on homelessness.

Those included Mary Ellen Carroll, the executive director of the Department of Emergency Management; Krista Gaeta, director of strategic initiatives with the Department of Public Health’s behavioral health division; and Dodge, the Department of Emergency Management’s manager of street response coordination.

Brainstorming sessions followed. The mayor attended many of these. Participants say one of the most valuable aspects of Lurie’s presence was that they had — and continue to have — his attention.

“The consistency and focus from the mayor’s office on this issue is critical,” said Carroll, who has led the emergency department for the past seven years.

Lurie’s experience at his nonprofit Tipping Point gave him a good understanding of the complexity of individual cases. Those in the working group said the mayor also conveyed a sense of compassion.

He wanted, said one, “to see people thrive, and a system that could work for a wide diversity of situations.”

The introduction of Modi added an outsider who “has a big capacity” for planning and, was not, as one person put it, “stuck in the way that we do things.”

The so-called team of teams was essentially the solution that the mayor’s office and department heads landed on. The silos of different city departments would be set aside.

Instead, there would be six street teams, each containing workers from seven different departments: Emergency management, public health, homelessness and supportive housing, police, fire, sheriff and public works.

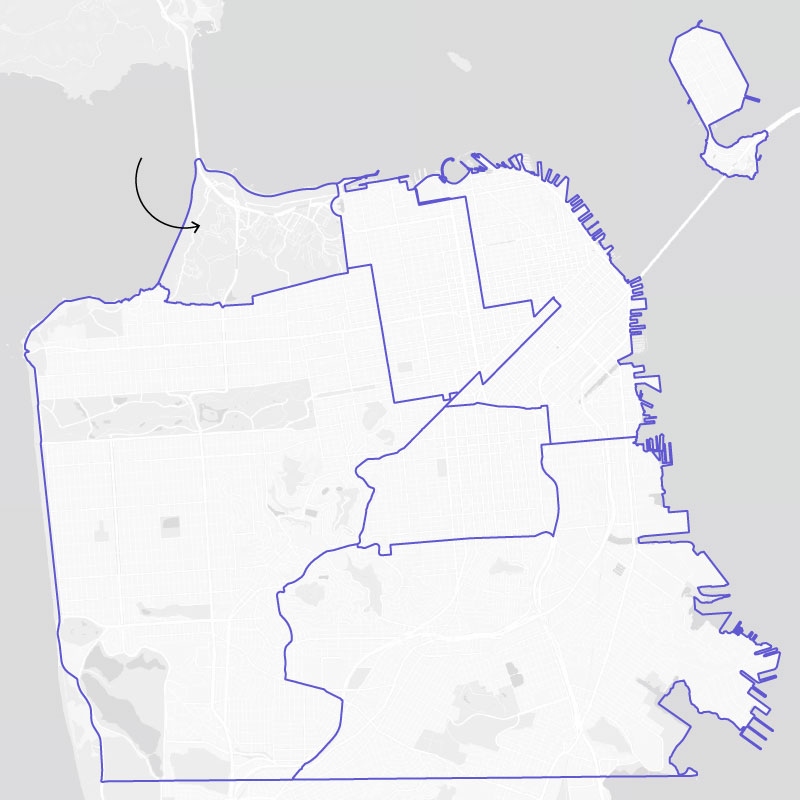

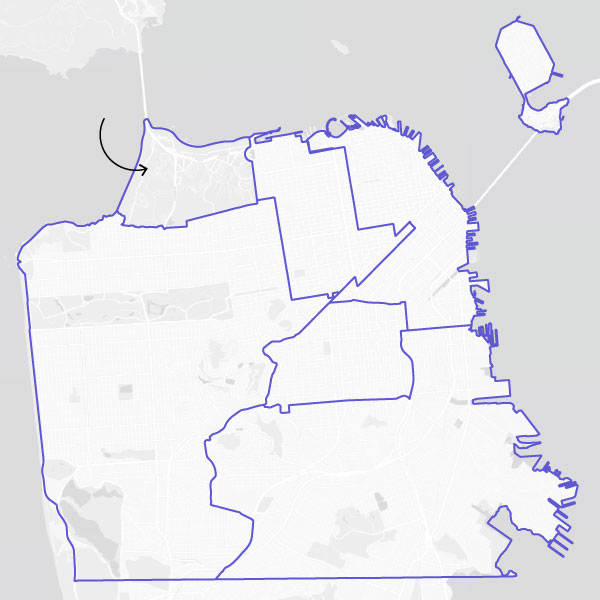

Five of the teams were neighborhood-based, taking their boundaries from police precincts: Mission, Tenderloin/Northern, Bayview/Ingleside, Park/Taraval/Richmond, and Central/Southern.

The sixth team was citywide, going wherever it was most needed or taking on more complicated issues that involve overlapping jurisdictions with the California Highway Patrol or Caltrans, for instance.

Map of San Francisco’s street teams

Presidio is overseen by teams

from neighboring areas

Central /

Southern

Tenderloin /

Northern

Richmond /

Taraval /

Park

Mission

Bayview /

Ingleside

Presidio is overseen by teams

from neighboring areas

Central /

Southern

Tenderloin /

Northern

Richmond /

Taraval /

Park

Mission

Bayview /

Ingleside

Basemap from Mapbox. Map by Kelly Waldron.

Before this system, Carroll said, “Everybody had different missions. They had a different direction that they were getting from a different person.” Now, she said, “The buck stops with us. There’s just a lot more clarity and span of control.”

The fact that it took a new mayor and fresh leadership to make this change has not gone unnoticed by workers on the ground. It’s funny how long it took the city to figure this new system out, one police officer at 16th Street said on a Sunday in March; he and a Public Works employee had just been laughing about it.

When we told one of Lurie’s team about that conversation, he laughed, too. “It kind of smarts a little bit, but there’s also some truth to it.”

‘Swiss Army knife’ teams scour the city

A look at a day in the life of Santiago Lerma helps illustrate the real-world impact of these changes.

For all of 2024, Lerma was a street-crisis-response coordinator, a lone figure walking through the Mission trying to keep the streets clean and clear of homelessness, drug use and illegal vending.

He focused particularly on the area around the Mission Cabins, a series of tiny homes near Mission and 16th for homeless adults.

All he had for solving problems was himself and an extensive knowledge of how the city worked, gained from 10 years as a San Francisco employee. “There was no team,” he said.

Now he has one. Every day at 8:30 a.m., he and the other members of the Mission’s street team hop onto a check-in call with representatives from city departments.

Typically, some people have already scouted the streets, finding tents and “problem individuals” in the neighborhood. The departments share how many people and what resources they have available that day, and the street teams make a plan.

On any given day, eight to 20 outreach workers join Lerma in the Mission. Homeless Outreach Team workers connect people to shelter and help manage cases for people who already have a bed.

Other outreach workers provide medical care. Paramedics from the fire department are on call, and the Department of Public Health sends out doctors and nurses with a variety of specialities including wound care and psychiatric care.

Meanwhile, police officers and DPW workers try to clear the streets, telling drug users, illegal vendors, and homeless people to leave the area and picking up any trash left behind.

Lerma says this new system has created more accountability. Before, street outreach workers would often encounter situations they felt unequipped to address by themselves.

A homeless outreach worker, trained to connect homeless people to shelters, for instance, could not treat someone’s leg wound and would call in a street medicine doctor who wouldn’t arrive until hours later.

Or, a Public Works employee assigned to pick trash off the street wouldn’t do it because an aggressive person was sitting on it. Instead, they’d call homeless outreach workers and the police.

“There was all this, ‘I can’t do anything about that,’ which was infuriating to the public, because it’s obvious there’s a mess here, it needs to be dealt with,” Lerma said.

The public doesn’t care whose job it is, technically, to address a problem, he added; they just want it done. “It’s like, ‘You’re the city. You need to figure out how to fix this issue.’”

Modi describes the current teams as working “more like a Swiss Army knife when we show up and have all those different tools available to us.”

The street outreach workers zero in on what they call “shared priority clients” — the 20 “most acute cases” in each neighborhood. These people typically have needs that stretch across multiple departments: They are both homeless and drug addicted, for instance.

Street outreach workers prioritize making contact with them every day, ensuring that they take their meds, checking on how they’re doing in a shelter they may be in, and whatever else they may need.

The hope is that, with more frequent contact, some of these people, who typically have been through the emergency room and jail many times, will be able to head down the path to recovery.

Lasting outcomes

Admittedly, it’s unclear whether the street teams are producing lasting outcomes: Are people actually addressing their drug addiction and finding permanent housing, or are they just rotating through the shelters?

When the police tell them they need to leave one place, are they finding shelter, or just moving to a different street corner that isn’t yet a priority?

In May, District 9 Supervisor Jackie Fielder posed these questions at a Board of Supervisors hearing, calling for the street teams to collect data and determine a metric of success.

After all, she pointed out, the situation at 16th and Mission streets is so dire in the first place because crackdowns on drug use downtown displaced people to the Mission.

Now, three months removed from the hearing, the city still hasn’t figured out a metric of success. In May, the Mayor’s Office of Innovation put out a request for private companies, nonprofits and others to send in suggestions for how to improve data collection so they can track outcomes.

They finished collecting answers in early June but are still in the process of evaluating submissions. The next step will be integrating them into the work of the teams.

Meanwhile, the police have defended displacement as a strategy, arguing that displacing people disperses large crowds and makes it easier to clamp down on drug dealing.

Five months since Lurie launched the new model, conditions near 16th and Mission — where the approach was piloted — have improved. There’s less loitering and open-air drug use on the west side of Mission Street and the alleys behind it.

Still, the east side of Mission Street remains a problem after 5 p.m., and Capp and 15th streets can be problematic throughout the day. Drug use and illegal vending on the east side of Mission Street still happens in full view of police.

Moreover, it’s unclear if the rampant unpermitted vending has simply moved to the 24th Street BART plaza, though on some days the 16th Street Plaza and the 24th Street Plaza are both clear.

It’s not perfect, Lerma admitted. Soon after starting, he realized that the Mission could use more people keeping the street clear, rather than having to rely mostly on Public Works and police, who sometimes get called away for emergencies.

So, the city hired Ahsing Solutions to work as ambassadors every afternoon and evening. Staff are instructed to keep the streets clear, and are a large part of why street conditions on the west side of Mission have improved so much recently.

Other ambassadors have been hired for mid-Market, the Tenderloin, and Lower Polk.

“I think now you’re seeing the full effort that we’ve been putting into this area,” Lerma said, though he also added that having even more people and shelter spots would help.

Multiple city workers have also noted that the teams often don’t have enough police staffing. Incorporating McChrystal’s team of teams model can only go so far.

The city is also working on “sequencing” the order in which different workers arrive in one area. Modi explained that when people are selling illegal goods on the street to fund their drug habit, the teams will start by sending in outreach workers to connect the people to shelter beds, addiction treatment and other medical help.

If they don’t clear out after this warning, though, the police will come in an hour later to move them away. Then, once the vendors are gone, Public Works and ambassadors clean the streets and keep the sidewalks clear of people.

“We have resource constraints, but we want to make sure we are being as efficient as we can with the resources that we have,” said Adrienne Bechelli, DEM Deputy Director for Coordinated Street Response, who came on July 1 and now leads the division.

For now, the city feels that the street teams have helped put conditions on the right track, and the mayor is still paying close attention. There’s a meeting every Wednesday with all the department heads responsible for street conditions, and the mayor usually attends.

While Lurie seems satisfied with the approach to date, staffers say he and department heads will set priorities for the street teams. It might be something as simple, Lerma said, as the mayor saying that if a city worker passes by someone lying on the street, they should check in on them and never just walk past.

“It’s a culture shift,” said Lerma. “It’s getting everybody on the same page that, ‘Hey, we’re not going to do this anymore’ or ‘We’re going to do this now.’”

The ends of “lasting outcomes” are in conflict with the means of “keeping the funding flowing.”

How about the City “prune the tree” by identifying street drug users who are not homeless, do not live in San Francisco, and thus do not need housing or services, and have no inclination whatsoever to get clean and to do what it takes to displace them from the Mission’s sidewalks by making it difficult for them to continue to use?

Then, once the city has constrained the problem to a more manageable size and is not setting scarce money on fire caring for an endless stream of the region’s willful addicts, more resources could be directed to addressing the difficult needs of those street users who are San Franciscans, are homeless, are amenable to housing or eligible for conservancy and would want to get clean given support.

Got a chuckle out of this. Go draw the Venn diagram of “street users who are San Franciscans, are homeless, are amenable to housing or eligible for conservancy and would want to get clean given support.” . Genius, you’ll save tons of money.

Some of those sets get inclusive “OR'”ed together.

The public policy questions are whether San Franciscans are going to waste valuable resources curing the region’s ills and if not, how those determinations get made, and what are we going to do with San Franciscan or SF homeless users who do not want to clean up?

It went from failed progressive run programs, “harm reduction,” and passing out free drugs and alcohol to accountability.

Progressives were “buying votes, and securing state and federal funding by using and abusing mentally ill drug addicts.

Let’s not forget the MAP program that provided free alcohol, typically vodka and beer, to homeless individuals along with temporary housing. Who wouldn’t take free booze, drugs and housing at the expense of the taxpayer dollars?

The fact that progressives advocated for unlimited “freedom to use” drugs and a lack of criminal consequences has led to addiction continuing and worsening the crisis in cities like San Francisco.

“It’s no surprise that an incoming mayor with no government experience might be dumbfounded.”

Don’t think so, we all know why this alphabet soup of organizations exists: Rent seeking. Remember, each org comes with a complement of administrators, directors, CEO or department head.

Quite the stretch, attempting to rope in an ex-generals military org philosophy into SF governance, and leaves the reader wondering what the goal was. Did Modi specifically call out McChrystal’s approach? Again, teams are one thing, flagging in McChrystal in this story is another.

Drawing on his experience leading the Joint Special Operations Task Force during the Iraq War, McChrystal argues that most bureaucracies, including city governments, have siloed people with different skills in separate departments, making it difficult to solve complex problems. Instead, organizations should create teams of people with different specialities and task them with a common goal. Dealing with complex problems, McChrystal argues, requires a team of teams, where “teams that had traditionally resided in separate silos would now have to become fused to one another via trust and purpose.”

I mean, they quoted his dogma and it seems pretty apt. What is your issue with the fact that he was quoted instead of say Rumsfeld or MacArthur or Sun Tzu? Myself I find agreeing with the advice because military bureaucratic problems are really not at all that different from other human bureaucratic problems, it’s all the same sand in the hourglass. If you can effectively run a warehouse you can effectively run a warehouse, and a lot of projects have the same underlying pieces of machinery. Making the comparison to a special ops General isn’t inflammatory when they quote him to make the minor point and it’s… spot on, really.

Point to the big stretch here because I’m not seeing you flesh it out. Modi doesn’t have to name McChrystal as the author of a similar plan, the author did that. If Modi was aware of it or not might be also interesting, but that’s not some lynchpin of the underlying theory.

Blending the silos and then sequencing the responses. Brilliant! Thank you Io and Lydia for this reporting. (Love the before and after sliding pics!)

I wonder if it would make sense for residents to be able to contact these neighborhood teams directly, instead of reaching out to the city-wide number where the response is often slow and with no follow-up.

lol

The city tracks it all centrally to manage funding allocations and efficacy counters. (Allegedly, as you point out.) The no follow-up problem is baked in but to have a city agency respond with umbrella-funding social workers within a few hours is actually not slow for a big-little city and county. We all want instant results and a certificate of accomplishment but that’s not the reality of 20 years of Gavin, Lee, Breed, and the rest of the talking heads establishment we’ve normalized by repeated self-immolation.

This is an excellent article But how can anyone formulate a plan when SF doesn’t even know what its population i.e disabled, vets those with no insurance etc, mentally ill These populations have differing needs

Second, SF is always behind the eight ball because its proximity to other cities A lot of homeless from Oakland come here and lie on the street when they are residents of Alameda or other counties yet SF has to take the financial hit Not right!!!!

Finally, a fair amount of these folks have a serious sense of entitlement When I was young I lived in Vallejo There was a homeless man who lived in field behind house My folks brought him food and my dad got him an army tent and a cot He never caused problems and actually foiled several burglaries He would tell my folks when we acted up Let’s just face the brutal truth-some of these folks don’t want to play societal rules Getting them to do so is the intractable problem in solving homelessness

[Jackie Fielder] “pointed out [that] the situation at 16th and Mission streets is so dire in the first place because crackdowns on drug use downtown displaced people to the Mission.”

She’s only partially correct. The situation at 16th and Mission is dire because her mentor Hillary Ronen and Emily Cohen welcomed more homeless and drug addicted into the neighborhood over residents’ objections. They then walked away from the containment sone that they’d made, leaving the neighborhood to deal with the fallout.

Spot on, Barbara !!

Marcos has been describing this scene in progression for the past two decades both as a homeowner and as top intellectual in the Think Tank that calls itself the Green Party.

I’m just the local Trash Picker with the dog who hounds the Armory hood.

go Niners !!

h.

Not included in McChrystal’s book is utter and complete failure in Iraq and Afghanistan of the US after spending under Bush, Obama, Biden and Trump an estimated $21 trillion. McChrystal’s JSOC operations prefigure today’s tactics used by ICE and the occupation of DC — sudden masked raids into people’s homes and snatching people off streets, killing, torturing or throwing them in prison). Echoing the cynical propaganda in Vietnam, McChrystal sold his program as “winning hearts and minds”. is it a surprise the people McChrystal tried to win over through management science didnt respond with flowers and hugs for their occupiers? Maybe they didnt get the memo or didnt have the organizational chart in their homes. According to the City Attorney SF has been mired in an “opioid epidemic” since 2000 thanks primarily to drug dealers Purdue Pharma and Walgreens. The new organizational chart will do nothing to change that. Its not about tactics and management, its about policy and strategy. Whack-a-mole has been the policy under successive SF administrations and it is the same now under Lurie. Maybe this will be a more efficient system for the same failed policy. Maybe not. Where did those hanging out on the west side of Mission go? Do the team of teams know? Permanent supportive housing, addiction recovery, jobs? Jail, busses out of town, residential blocks? Hunters Point? Or maybe Trump brings in his “team”and hires MCChrystal “consultants”, to round up all undesirables, and ship them off to a concentration camp (“humanitarian city” is phrase now in vogue in Gaza) or simply kill them on the street and have the team of teams pick up the bodies.