On a recent Thursday at Joe’s Pharmacy on Geary Boulevard, Tony Bastian sat down with three patients who were confused about their prescriptions, and explained each drug. At one point, he received a call from a patient’s son, who told him that his dad just passed away. “You did what you could, my friend,” Bastian comforted the distressed son over the phone. “I am your witness.”

That’s not a rare scene at local, independent pharmacies in San Francisco. But pharmacy owners say they can’t hang in there for long, blaming pharmacy benefit managers, a middle entity between pharmacies, health plans and drug manufacturers. The middle entitities, they said, profit from each aspect of the system.

“As pharmacists, we are the weakest link, and everyone is taking advantage of us,” said Bastian, owner of Joe’s Pharmacy.

The pharmacy benefit managers, which are for-profit businesses, control how much pharmacies are reimbursed from insurers, large employers and other payers for a drug. At the same time, they charge fees — pharmacies say they are arbitrary — for each prescription, according to pharmacy owners and advocates. In the end, the amounts pharmacies are reimbursed are lower than, or just about at cost, for the drugs dispensed.

There is no comprehensive data on how many independent pharmacies have closed in San Francisco over the past decade. One pharmacist said about 20, and another said 50 to 100. But one thing is clear: Many are under pressure because of low reimbursement rates.

That may change with State Sen. Scott Wiener’s SB 966, which would require all pharmacy benefit managers to be licensed under the California Department of Insurance, and to disclose information about their business practices. It also prohibits pharmacy benefit managers from steering patients to affiliated pharmacies, or charging an insurer more than it reimburses pharmacies.

“I believe we have a path to get it to the governor,” said Wiener, noting that the bill passed the Senate unanimously three weeks ago, and is now headed to the State Assembly. By October, the public will know whether the bill will become law next year.

In the meantime, pharmacies in San Francisco say the changes are long overdue.

The owner of one pharmacy in the southern part of the city, for instance, paid $5,103 for a prescription of Invega Trinza, a mental-health treatment drug, and only received $4,301 in reimbursement, costing him some $800 on a single prescription. For another prescription of Vivitrol, a drug that prevents alcohol and drug withdrawal relapses, the owner lost $128.

“I’m working much harder than 39 years ago. We’re making much less than what we were making 39 years ago,” said Bastian. “This doesn’t make sense.”

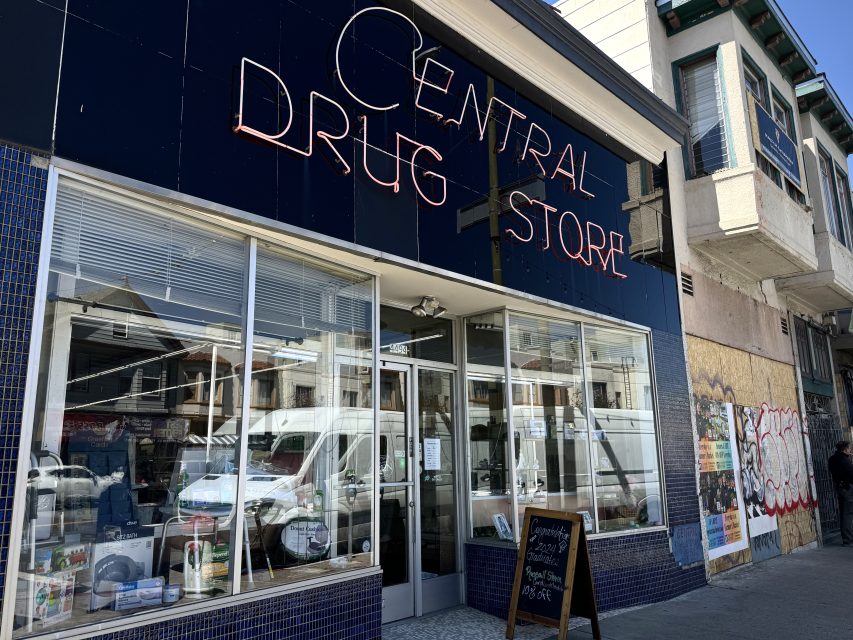

Already, the number of independent pharmacies has been dramatically reduced because of consolidation and competition. In the late ’70s, there were some 300 independent pharmacies in San Francisco, but fewer than 20 are left, said Jerry Tonelli, owner of Central Drug Store in the Excelsior District.

Pharmacy benefit managers came into existence in the 1960s, but here, too, there has been consolidation: The largest three pharmacy benefit managers today — CVS Caremark, Express Scripts and OptumRx — own pharmacies as well as health plans. That allows them to steer patients away from independent pharmacies to their own businesses.

How it’s meant to work: Insurers and employers pay benefits managers for help managing health plans and claims, and the benefits managers determine how much they will pay pharmacies for dispensing drugs to those covered by a health plan.

In practice, the pharmacy benefit managers reimburse pharmacies less on a claim than what the insurer paid the benefits manager for the claim, pocketing the difference, according to the National Community Pharmacists Association.

But pharmacies must use benefits managers because insurers work with them. Deciding to opt out would mean a pharmacy could only take customers without insurance who pay for all of their prescriptions out of pocket.

Benefits managers, however, say they are lowering drug prices for patients and health plans.

“[Pharmacy benefits managers] are the only entity in the drug-supply chain that exert downward pressure on drug prices by negotiating rebates and discounts with manufacturers,” said Bill Head, assistant vice president at the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, the trade association representing benefits managers.

The profit margins for pharmacy benefits managers, Head said, are in the 3 to 5 percent range.

It was only “in the last five or six years that [benefits managers] have grown so exponentially,” Wiener said.

Pharmacy owners, too, said this has been a problem for the past decade, but that it has grown worse in the last two years. David Valencia, a pharmacy manager at Reliable Rexall Sunset Pharmacy in the Inner Sunset, said it has been “the most difficult two years in pharmacy that I’ve seen in 47 years.”

“The lack of accountability and regulation has led to a real imbalance,” said Susan Bonilla, chief executive officer at the California Pharmacists Association. “If we let this go unchecked, more pharmacies will go out of business, and that is going to hurt patients more than anything.”

Wiener’s legislation would add some direct oversight over benefits managers, and prevent pharmacies from being underpaid. It would also prevent pharmacy benefits managers from steering patients to their affiliated pharmacies.

The bill, however, faces strong opposition from the benefits managers themselves, the health plans they own, and possibly the California Chamber of Commerce, Bonilla said.

At present, California is lagging behind other states in regulations on pharmacy benefit managers. Across the county, 25 other states have required benefits managers to be licensed, including New York, Georgia and Michigan. That would happen if Wiener’s bill succeeds, but at present, they are not licensed.

Because the regulations in other states are relatively new, the immediate outcome is still unclear, but Wiener believes “it appears to” be effective in lowering drug prices.

A National Community Pharmacists Association’s internal analysis supports the belief: Premiums in states with “comprehensive [pharmacy benefits manager] reforms” were increasing at a slower rate than the national average.

All six independent pharmacy owners interviewed said they are especially taking losses on high-value branded drugs such as anti-diabetic medications like Ozempic and Zepbound.

On generic drugs, pharmacies make somewhere between 30 cents and $10 — often not enough to cover the costs of utilities, labor and supplies like drug bottles and labels, which are about $13 per prescription, according to pharmacists interviewed in the story. But on branded drugs, “they are flat-out negative,” said Kevin Komoto, a board member of the California Pharmacist Association and a pharmacy owner in Delano, near Bakersfield.

At the Central Drug Store on Mission Street, about 30 to 35 percent of the prescriptions filled are under-reimbursed, the owner Tonelli said. Recently, at Joe’s Pharmacy, the owner said he lost money on 50 percent of their prescriptions.

On top of the low reimbursements are the direct and indirect remuneration fees, known as DIR fees, for patients’ compliance and small errors that remain unclear to the pharmacies. These can be simple errors, such as not fully spelling out a prescription on a bottle. Often the pharmacies are unclear why they were charged the fee, and said the fees are arbitrary and unpredictable.

“There’s no rules on what metrics you have to hit,” Komoto said of the fees.

Mission Wellness, a specialty pharmacy at Mission and 20th streets, won a case in 2022 over such fees charged by CVS Caremark. It alleged that Caremark’s fees siphoned off a sum equivalent to 150 percent of Mission Wellness’ net profit in 2020. The arbitrator ruled in favor of Mission Wellness, and ordered CVS Caremark to pay $3.6 million plus interest.

Until recently, these fees were assessed weeks or even months after prescriptions were filled, causing pharmacies to only realize retroactively that they did not recoup their costs — a serious cash-flow issue for independent businesses.

Starting this year, after a ruling from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, these fees must be applied at the time of purchase, instead of retroactively.

Today, independent pharmacies sometimes have to make the difficult decision to direct patients to the big pharmacies, like Walgreens or CVS, because they can’t afford to fill a prescription themselves.

“I really don’t want to send them there,” said Valencia of Rexall. “When you go to Walgreens, you have to wait two hours to get a script. You can’t get anybody there. You never get the pharmacist to come out and talk to you.”

Bonilla, the California Pharmacists Association executive, fears that when independent pharmacies close down, patients will end up losing the relationship with their pharmacists altogether. “Right now, the pharmacy is the one medical place where you can go in without any appointment and get help.”

Central Drug Store, for example, has been a neighborhood institution since 1908, and Tonelli, now 70, has been working here since he was a junior in high school. His father started working at the pharmacy in 1949, where he met Tonelli’s mother. But Tonelli worries that he might be the last in his family in this profession.

When pharmacy students call and ask him questions, Tonelli tells them: “Don’t go into retail. Use your knowledge. Do research, or work for a hospital.”

The hardest part, for him, is knowing how much his patients depend on this pharmacy. Central Drug Store is the only pharmacy left on the two-mile stretch of Mission Street between the Walgreens on 30th and Safeway on France Avenue.

A lot of independent pharmacies that are still surviving have diversified their services — offering clinical services on diabetes management, vaccines and immunizations, or just watching inventory more closely and selling merchandise in the front.

“Honestly though, to this day, the bread and butter for most pharmacies is to serve the public,” Komoto said. “But if something’s not done quickly, we’ll be out soon.”

Horrible law aimed at guaranteeing higher prices to the pharmacies. Don’t be fooled, this is NOT about saving small pharmacies, it’s about guaranteeing higher profits for all who donate to our politicians. These “middle men” as they call them, are the only consumer advocates keeping us from paying upwards of 1000% markeups – I am your source as I use Good RX (a “middle man”) to force pharmacies to charge fair rates.. Yes, they profit still, but I pay pennies on the dollar. Still higher than Canadian customers, but best we are going to get in the current corrupt system in the US.

I do not agree at all.

EVERY TIME you add a “middle man” or third party administrator you pay more to assure that middle man gets their share. You never save money. GoodRX is not a middle man.

I LOVE my locally owned pharmacy and its owner. I want him to be able to earn a profit and stay in business.

Thank you for writing this. Such an important conversation. Independent pharmacies offer an important service to the community – timely personalized care and advice. I’ll now be patronizing the pharmacies you mentioned in the article and hopefully avoiding the products the make a loss for them.

I use the Reliable Sunset Pharmacy on the corner of Irving Street and 9th Avenue. I wish that they had greater access to medications because I would like to use them exclusively.