Shamann Walton didn’t do the armed robbery. He didn’t leap out of the car while brandishing a weapon and relieve a random passer-by of a watch and some cash. In fact, that would be Walton’s lifelong friend Chuck Smith. He cops to it. “We were trying to get money to get alcohol and chill with girls,” Smith explains.

Well, fair enough. But when the police showed up, Smith was arrested merely for not putting his hands up promptly enough. Walton, however, was pinned with the robbery and carted off to juvenile hall.

It wasn’t the first time. It wouldn’t be the last.

Walton’s first experience with incarceration came after he was jumped at age 15; he responded by retrieving one of the guns he and his friends usually kept secured in a secret place and bringing it to Vallejo Junior High School. (He was also expelled for this — making him the rare individual to have this on his resume along with subsequently serving as president of the San Francisco Board of Education.)

After that, there was the stolen car attempt in Pinole. Then came the armed robbery case, which was eventually dismissed. And, finally, there was a probation violation — his own mother caught him with drugs and money — that led to Walton being locked up one final time at the juvenile hall in Fairfield. Somewhere in there he was also nabbed with crack cocaine and charged with possession with intent to sell, but let off with a citation: Juvenile hall was full.

That was nearly 30 years ago. And, now, juvenile hall is virtually empty. If Walton has his way, it will be closed.

Walton, 44, was handily elected supervisor for San Francisco’s District 10 in November. His district is composed of Bayview, Hunters Point, and much of the city’s traditionally underserved African American southeast. And both he — and his background — are in the news of late because of legislation to shutter juvenile hall that he’s quarterbacking, along with Supervisors Hillary Ronen and Matt Haney.

In line with a statewide trend, San Francisco’s juvenile detention population is dwindling: There are days in this city of 885,000 that fewer than two dozen children are kept under lock and key. But Walton and his colleagues claim that applying the cuff-’em-and-stuff-’em approach to children isn’t just costly and passé — it’s a vindictive and reactionary practice that does more harm than good.

This is an argument that experts have been making for years. As has Walton. “The only thing you learn in juvenile hall is how to be institutionalized,” he says. “You know how to survive county jail because of your juvenile hall experience. You know how to survive the pen because of your county jail experience.”

Kids compare notes on how they were caught. Budding criminals are professionalized.

Shamann Walton’s past wasn’t a secret. Anyone in his pajamas could Google a number of articles, blog posts and bios, including this 2015 Vallejo Times-Herald profile, in which Walton notes, “I spent several stints in juvenile hall. I was expelled from the Vallejo City Unified School District on more than one occasion and I was a teenage father (a daughter named Monique and a son named Malcolm).”

But, while Walton wasn’t hiding his past, he wasn’t shouting about his politically potent redemptive tale at every opportunity, either. Ronen tells me that, prior to collaborating on this legislation, she had no idea about Walton’s upbringing. Your humble narrator moderated two 2018 District 10 debates, during which a number of the candidates were rather candid about their evocative life stories. More than one experienced homelessness; one spoke of addiction and living in an honest-to-God cardboard box. Another talked about his father slipping into homelessness and dying on the street.

Walton, however, did not bring up his own evocative background. A compelling story can take you a long way in politics in this and every city — way further than compelling policy proposals. But Walton apparently feels that his compelling story is not the crux of his political persona or ethos.

If you’re already familiar with Walton’s tale, you might well have been an at-risk or incarcerated young person he worked with. He has chosen to talk about it in recent mainstream news articles in pursuit of a specific, germane policy goal: shuttering juvenile hall.

Walton says that political consultants have told him to “use your story.” But he has resisted the advice. “For me,” he says, “it has to be relevant in helping somebody.”

When Hillary Ronen’s legislative aide, Carolyn Goossen, saw the statistics unearthed by the Chronicle’s Jill Tucker and Joaquin Palomino, she screamed out loud, right in the office. Goossen has been working to close this city’s juvenile hall for roughly a decade and, thanks to Tucker and Palomino’s fantastic, thorough, and thoroughly damning investigation of juvenile halls as costly and questionably efficacious, she saw an in. Walton and Haney were soon brought into the mix.

It’s not as if Walton read the paper and decided to do something about this. Eight months ago — prior to his election — he told Maria Su of the Department of Children, Youth, and Their Families that he intended to close juvenile hall. Five months ago, back in December, he told the same to Allen Nance, the city’s chief juvenile probation officer.

“It was always the right thing to do, but timing is everything. And that article gave us all the data and information about not only San Francisco but across the state,” Walton says. “We’ve had data and information but that reporting got it out to everybody. Now we have the will and the political leadership.”

In fact, the legislation to shutter juvenile hall by December 2021 now has the support of eight supervisors — the critical threshold to overcome a mayoral veto. You can read it here: This is not a clandestine maneuver to funnel children into the adult lockup nor to coddle dangerous young people and release them back into their communities with a mere admonishment.

In fact, Meredith Desautels, the staff attorney for the Youth Law Center, notes that among cases that were sentenced in San Francisco last year, 96 percent of juveniles were released back into their communities (178 of 186). So arguments for preserving the status quo lest a wave of miscreants be unleashed on San Francisco’s vulnerable neighborhoods do come off as fearmongering.

Nobody is suggesting young Hannibal Lecter get off scot-free. Rather, Walton et al. are hoping to remove the other 96 percent of incarcerated youth from an institutional setting and instead allow many of the organizations that already visit juvenile hall to have even greater access to them in residential facilities.

This, Walton says, will be more conducive to young people’s needs and mental health. It will cost less. We only have two or three dozen young people detained, so why not shift to a more individualized model? Why not try what experts tell us would work better instead of what we’re doing, which isn’t working and costs more?

PG Anniversary:

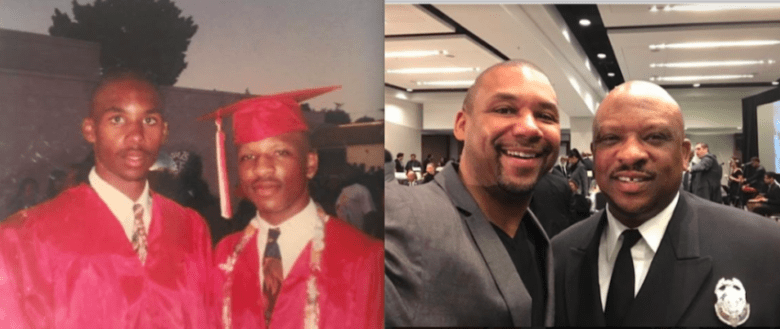

This man took me to this conference, which led me to this college and helped shape the man I am. Today on the anniversary of Philmore Graham’s death. I want to honor him and give thanks to God for giving him the vision of connecting youth to higher education. pic.twitter.com/JrsXyEw1l5

— Shamann Walton (@shamannwalton) June 12, 2018

High in Shamann Walton’s office, nearly nine feet off the ground, hangs a picture of a pensive, bespectacled African American man. You could say that Philmore Graham is still watching over Walton.

The founder of the Omega Boys Club in Vallejo died in 2014 at age 75. But not before providing opportunities and structure and guidance for countless children, Walton among them. “Who’s to say where we’d be if Mr. Graham didn’t intervene in our lives?” asks Mario Riley, a friend of Walton’s since childhood and now a San Francisco firefighter. “Mr. Graham’s involvement in our lives did not happen overnight. It took years.” He got to know young men. Got to know their teachers. Got to know their friends. Challenged them. Quelled the potentially lethal rivalries stemming out of schoolyard fistfights among day-drinking teenagers.

Walton’s best friends are still the half-dozen or so guys he used to play football with in Vallejo as a pre-teen. Many of them, like him, got in trouble with the law. Some went to jail. But, eventually, most all of them went to college, too. Got good jobs. Raised families. Made something of themselves. Philmore Graham is in the center of all of their Venn Diagrams.

He made the difference that being locked up in an institution could not. He put them on an alternative path.

“People have our legislation. They can look at what we’re talking about,” says Walton. “This is an alternative. That word is key.” Potential opponents are “focused on the ‘shutdown.’ But we are focused on the alternative.”

“We need to put our young people into an environment that doesn’t say ‘we are throwing you away.’”

Why is the media so hellbent on making Shamann into a Saint? He might be better than some politicians, but he turned a blind eye to some dirty dealings while he was on the school board.

Excellent. As Joe said, timing and political will. Doing the best for children—thanks for history and why we need to close Juvenile Hall and provide public support for children who need residential care.

Campers,

About 20 years ago the ‘Class of 2000’ fielded an offer from the State

to build a Juvenile Hall but it was way too big for our needs.

I argued with Tony Hall that they should take the money and just use

the extra space to store toilet paper or something.

As someone with decades of working with delinquent youth I assumed

it would get filled.

Sadly, it did.

Now, I’d convert it to transitioning youth.

Whatever, don’t allow Breed to tear it down.

That’s housing sitting empty in front of the ‘Family’.

Already zoned for housing most shunned of community.

At least make it a huge Navigation Center.

Go Giants!

h.

Nice job, Joe.

Thank you, Amie!

Joe, juvenile crime has actually increased in SF. The Chronicle series measured a decline in Juvenile arrests as equally a decrease in juvenile crime . “Crime” and “arrest” have different meanings. Why didn’t the Chronicle seek juvenile crime stats via a public records request?