This is the second part of a two-part series on architecture at 16th and Mission streets. Read the first part here.

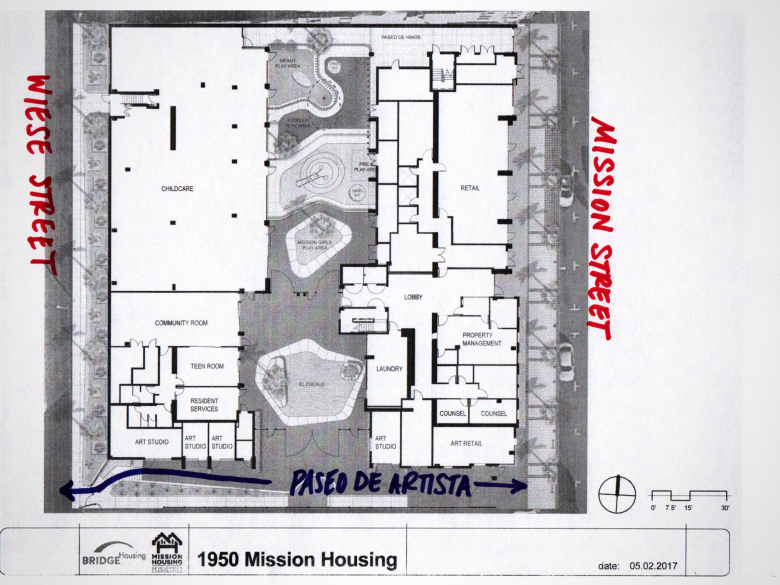

When David Baker Architects and Cervantes Design Associates designed La Fénix at 1950 Mission St. in 2016, they envisioned an open walkway — a paseo de artistas — cutting through the southern edge of the development from Mission and Wiese streets.

Large gates on Mission Street would be open during the day, inviting pedestrians to traverse the interior of the complex and exit onto Wiese Street. They would walk along the pathway, past artists’ studios, murals, and maybe food stands or occasional celebrations with music.

“We propose to create a lively village that reinterprets the diverse texture of the neighborhood, by combining supportive housing and resident amenities with community and public space,” the planning documents state.

That was before the pandemic, before encampments and before the chaotic, unpermitted vending and unchecked drug use on Mission Street that Mayor Daniel Lurie is now trying to tame. But, even then, the idea of an open art paseo was both daring and aspirational, because Wiese Street was already a hangout for homeless residents and drug users.

The idea never met reality. The large gates at both ends have never been open to pedestrian traffic. A plan to make the commercial space lining the paseo into low-cost artist studios was shelved and the space was rented out to three nonprofits instead of the active retail that Anne Cervantes, the founder of Cervantes Design Associates, had proposed after community outreach.

The only remnants of that vision are three colorful murals on the wall along the paseo and a setback on the Mission Street side, now often occupied by unpermitted vending and an open-air drug market.

Nowadays, people defecate against the gates at either end. On at least two occasions, someone jumped the Wiese Street gate and used a crowbar to break into the Youth Art Exchange on the ground floor. The gate’s height has been increased.

As former police captain Al Casciato noted, the setback designed to open Mission Street has instead become a convenient nook for users, dealers and unpermitted vendors.

I’ve visited dozens of times and can count on one hand the times I didn’t observe overt drug use in the setback. And one of those times, a dealer and buyer ducked in to quickly exchange cash for a small packet containing a white substance.

In Part 1 of this series, the architect David Baker and the three nonprofits on the ground floor of Le Fénix were enthusiastic about the possible benefits of making the tinted windows on Mission Street clear.

The change would signal the vibrant activity happening inside: Teen art programs, a bicycle repair shop and immigrant organizing. That, in turn, might make those on the street less likely to use the sidewalk as an open-air drug and unpermitted vending market.

The change would, as the urbanist Jane Jacobs wrote in 1961, put “eyes on the street,” a principle that continues to influence urban architecture. “It took the Jane Jacobs generation to rescue the ground floor from insignificance, and to reassert the value of social, civic and economic encounter at street level, “ wrote Benjamin Grant, director of planning and resilience for SITELAB Urban Studio, in a 2014 post for SPUR.

If the gates can’t be opened to a paseo, the setback they create on Mission Street is a more challenging problem than removing tinted windows.

Raffaella Falchi, the executive director of the Youth Art Exchange, which has an entrance near the nook, would love to see the setback disappear by making the entrance flush with the building. Baker, the architect, points out that doing so would cost “a bunch of money” and wonders if that is not a red herring for other, more systemic, problems of drug use, homelessness and “the breakdown of civility.”

In the short term, however, minor architectural interventions could help. On a recent Saturday, for example, someone had erected a low metal barricade in front of the setback. It only partially covered the nook, but its impact was remarkable.

The drug users and vendors loitered in front of the barricade. They did not bother walking to the other side, where they would have been more comfortably out of the pedestrian path. The simple barrier sent a message of a no-go zone.

What would happen if there were planters instead of a barricade? Or if planters filled the nook? Or, Falchi suggested, the space could be used for exhibiting art or other projects?

Conversations with the urban landscape can work

To get an idea of how architecture might affect life at Mission and 16th, I stopped five blocks east at Casa Adelante. There, at 2060 Folsom St., the architects at Mithun and Y.A. Studios designed a pedestrian walkway similar to the one that has so far failed to work at La Fénix.

In the planning documents, they promised a public promenade “providing a ‘front porch’ and allowing the building to engage the community.”

It runs west from Folsom to Shotwell streets, in an area where encampments appeared during the pandemic and where homeless residents are often seen. But there is no loitering or open drug use on the promenade.

In Jane Jacobs’ parlance, there are eyes on the promenade. The ground floor of the 127-unit affordable housing complex looking onto the promenade has floor-to-ceiling windows, but none are tinted.

Pedestrians can look in and see offices, bookshelves and meeting rooms. Those inside can see anyone on the pedestrian path. The large gates at either end of the walkway are open during the day, and closed at 6 p.m.

Erik Auerbach, executive director of the nonprofit First Exposures, which introduces young people to photography, said that people hang out on the benches during the day, but they’ve never had problems and everyone is respectful.

He might have security for a big event, but it doesn’t seem needed during the day, he said.

What accounts for the difference between Folsom and Mission? It’s unclear whether the ground floor’s engagement with the pathway at Folsom discouraged trouble from ever developing, or if the immediate area simply doesn’t have the overwhelming problems that Mission does.

It’s not immediately outside a major transit hub, after all, and does not have the reputation that 16th and Mission has had for years. On the other hand, Mission Street’s natural foot traffic with transit riders heading to BART or Muni gives it the potential to discourage loitering.

Yakuh Askew, the founding principal at Y.A. Studios, said the Folsom development had an advantage because the windows look out onto a park. “It feels open and inviting and secure and there’s plenty of visibility,” he said.

Making La Félix’s windows open to Mission Street, an idea the three nonprofits expressed enthusiasm for, would increase the conversation with the street, he said.

“It would also help if the nonprofits on the ground floor increased their programming and felt active, he added. Faith in Action already gathers in its space daily, but the other two have less frequent programming, in part because of the daily scene in front of their offices.

Can Wiese Street be activated?

The Mission to Wiese corridor near the BART plaza is tricky, Askew said, because there is no reason to go to Wiese Street. It is an alley with no shops, and the path doesn’t make one’s trip to BART faster. The garages and residences on Wiese mean you can’t block it off and activate it as a park.

But the Mission also has a history of activating difficult alleyways. Take Balmy Alley, off of 24th Street. In the early 1970s, the alleyway leading to 24th Street was littered with discarded liquor bottles.

Artists like Mia Galaviz de Gonzalez, one of the founders of Balmy Alley, sought a better environment for the girls who attended a nonprofit on 24th Street, where the artists worked. To make Balmy safer and more appealing, they cleaned up the alley and asked homeowners’ permission to paint murals on their garage doors. Now, some 50 years later, the alley remains a destination for tourists visiting San Francisco.

“I think it could happen,” on Wiese Street, said the architect Cervantes, and pointed out that the murals on Balmy Alley were connected to the politics of the day, including local Latinx artists being left out of the mainstream art scene and the wars in Central America that many Mission residents had fled. Those on Wiese Street, she suggested, could be connected to this moment, like the threat of ICE and deportation.

And the residents living inside La Fénix would likely have stories to tell.

Security

To change the dynamic at 16th and Mission streets, nearly everyone involved in 1950 Mission St. agreed that any architectural changes to activate the nook, make the windows clear, put out planters or add sidewalk designs would need to be accompanied by increased security.

The question, said Sam Moss of Mission Housing, which co-developed La Fénix with Bridge Housing, is who will pay for it. No one has a bigger interest in the immediate area than Mission Housing. It counts four buildings in its portfolio in the 16th and Mission Street area.

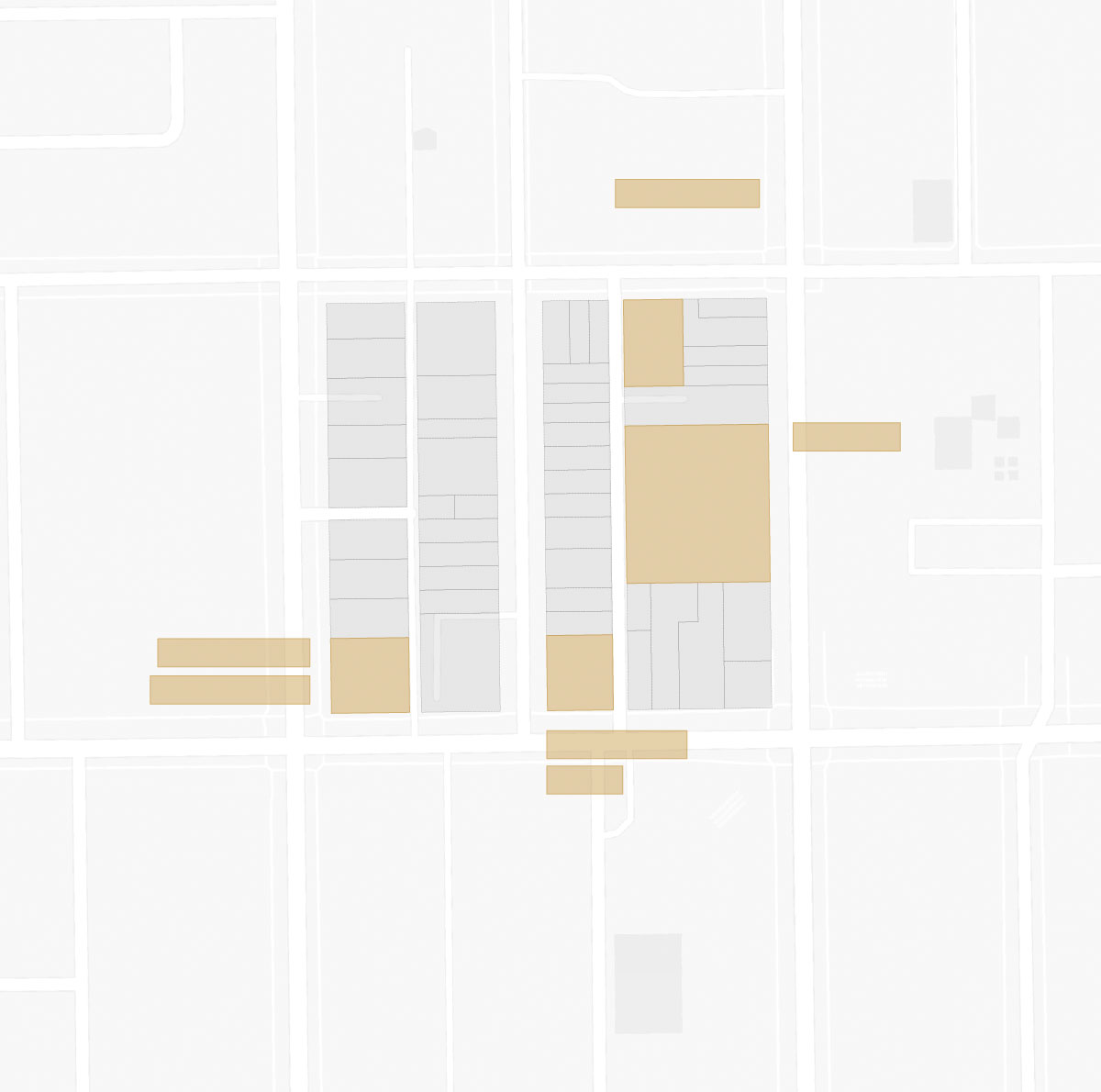

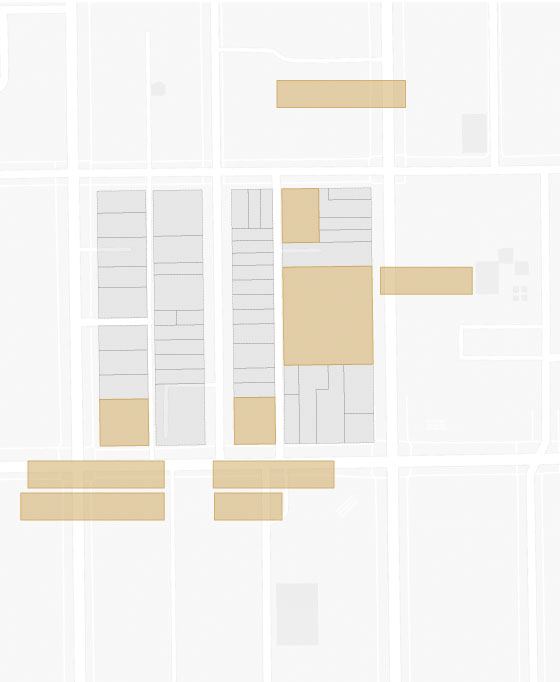

Valencia Street

Small sites

16 units

1637 15th St.

15th Street

La Felix

157 units

3 commercial spaces

1950 Mission St.

Maria Alicia

Apartments

20 units

2 commercial spaces

3090 16th St.

16th Street

Altamount

Hotel

88 units

2 commercial spaces

3048 16th St.

Mission Street

Valencia Street

Small sites

16 units

1637 15th St.

15th Street

La Felix

157 units

3 commercial

spaces

1950 Mission St.

16th Street

Maria Alicia

Apartments

20 units

2 commercial

spaces

3090 16th St.

Altamount

Hotel

88 units

2 commercial

spaces

3048 16th St.

Mission Street

Source: Mission Housing. Map by Junyao Yang.

Already, Mission Housing pays for a guard at its building on Caledonia Street, but Moss says that, despite the “amount of tragic awfulness,” there is no money for a guard on Mission Street.

“We don’t control the state of the street,” said Moss. “We have no jurisdiction on public ground.” Police, he offers, could park a car in front of La Fénix 24 hours a day.

Sounding like any property owner, Moss worries about crossing a Rubicon if he pays for full-time security. “We will never be able to stop it, and we set a precedent for the police not doing their job,” he said.

The way affordable housing is funded, he said, security is not included. However, with a new mayor who is intent on expediting solutions, perhaps there is some room for negotiation.

Mission Housing’s co-developer, Bridge Housing, is the property manager. After Bridge declined an interview request, Randy James, a spokesperson who works with Bridge on communications, sent an email Monday evening, detailing all that had been done: Increased security at the front desk, new security cameras, meetings with all the concerned parties and increasing the height of the back fence were among the items in the email.

James said the increased security will be working with an ambassador’s program and police to keep the sidewalk in front of the building clear. A new manager was hired and started June 24th, he added in a subsequent email.

In recent days, the mayor’s office has added an eight-member team from Ahsing, a community safety and engagement organization. In addition to the existing assistance from the Department of Public Works and the San Francisco Police Department, Ahsing began Saturday to patrol Mission and the surrounding streets.

The impact was notable. The crew, all of whom are transitioning from jail or in recovery, kept the west side of Mission Street clear of illegal activity and free of debris for two consecutive weekend days, a first in months.

Sustaining that change will take months, but Baker, the architect who lives on Shotwell Street, said a police and city operation on Shotwell to control cruising by sex workers and their clients succeeded after about six months.

Falchi from Youth Exchange understands the need for security. When she opened her space for the art exhibit, “I literally had to follow people around, because they were clearly, like, trying to scope things out,” she said.

She won’t have another open event without a guard, but does not seem inclined to get in a standoff over who will pay for it. Already, she’s making estimates and plans.

Falchi has received multiple complaints about the scene outside her door from parents whose teens participate in her art programs, to the extent that Mission Housing suggested she could terminate her lease, but Falchi is committed.

“That’s not a solution,” she said. Like others who lease there, she’s determined to make her space at La Fénix work. She applied for, and recently received, a grant to improve the outside signage.

And she’s looking into changes in the architecture. She plans to hold a design competition on Oct. 25 that will ask students to “reimagine Wiese Alley and the segment of Mission Street between 15th and 16th streets through a youth-centered lens.”

Proposed interventions “may include physical improvements — such as lighting, seating, street furniture designs, greenery, and traffic calming — as well as programmatic strategies that support creativity, safety, and social connection.”

Jane Jacobs couldn’t have said it better.

One of the main obstacles to making the front entrance to a building “flush” with the rest of the building, as Ms. Falchi and the retired police captain who you interviewed for this piece, is a city imposed bureaucratic obstacle. If you’re building a new building and you want the front door to swing past the property line onto the public sidewalk, you’ll need a to get an encroachment permit from the Department of Public Works. The process for getting an encroachment permit from DPW is agonizingly Kafkaesque, to the effect that it’s practically impossible to get one. So the typical response by most architects and developers is to set the entrance back so there’s enough room for a door to swing outward without crossing over the property line onto the public sidewalk. I’ll admit, on a general level this is good policy. It wouldn’t be good for flow of pedestrian traffic, especially for folks with mobility/ visual impairments, if the doorways for every building swung out onto sidewalks. But in parts of town that are known hotspots for drug use and crime, DPW should be willing to entertain exceptions to this policy. The result would be fewer nooks and crannies like the ones at 1950 Mission that provide easy cover for people to engage in unsavory activities.

And for those of you wondering “why not make the doorways swing inward so you can have an entrance that doesn’t require a setback or an encroachment permit from DPW? ” – the Fire Department won’t let you do that. For any major entryway or other portal that might be used as part of an evacuation route in an emergency, the door needs to swing outwards with push bar “panic hardware” so that large amounts of people can get out of the building as quickly as possible. Again, this is sound public policy, I’m not saying we should do away with this safety requirement. But part of the problem is that when you start to layer arbitrarily enforced requirements from other city agencies on top of it, you tend to get watered down design outcomes that nobody likes.

There is lots of wisdom in Jane Jacob’s “Death and Life of Great American Cities”. But it should be noted, a lot of her observations of what worked were in places like Greenwich Village, with a lot of older buildings that predate WW2 or even the 20th century (e.g. when most cities hardly had any building code requirements). A big part of the disconnect between her ideas, and what tends to get built nowadays is that it’s difficult for them to survive through the meat grinder of 21st Century building codes – especially in places with complex and dysfunctional regulatory environments, like San Francisco.

Thanks for a good laugh this morning, the idea that the architects thought that paseo was going to work out is hilarious in a dark and horrible way. Did they ever even walk down Wiese? It’s not a street, it’s an alley and no one lives on it, it’s not like Balmy – no one is invested. There were loiterers and tents and problems long before the pandemic, long before 2016. The gambling den is gone, but honestly I think they kept the street a bit cleaner, if you didn’t count the fights, the boom cars cruising by, the murders, etc.

There is also a setback on Wiese that is constantly used for drugs and defecation that needs to be dealt with. They put up a fence around the garden area on that side in the past couple weeks which makes the space where people can’t be seen from 15th/16th smaller, that helps a bit. That you didn’t mention the new fence makes me wonder how often you walk the street.

The real problem is that this neighborhood has been designated as a containment zone. You can’t architecture your way out of that decision (no matter how much the powers that be deny the decision). And the reason people moved to Mission Street is because the neighbors and merchants demanded they be pushed off of their streets. The real question is where are the drug users going to go next once they are pushed off of Mission, because they aren’t going “away”. Which lucky neighborhood gets to be the next containment zone?

Maybe we could help people who need help instead of displacing them, and then we wouldn’t need containment zones.

But I guess Lurie is unlikely to smile on such a “far-left” idea, as opposed to the pragmatic, centrist strategy of endlessly repeating what doesn’t work.

What do we do with the people who refuse treatment and insist on taking drugs in the open every day in front of a school? Just wait for them to change their mind?

Arrest, cite, fine, and throw people in the drunk/druggie tank for a couple days every time they get high there and the problem will stop very quickly.

The problem is not architecture.

No amount of architecture or urban design will remedy the situation in the Mission District because it not the proper tool to effectively address the underlying chronic problem.

Note: It is quite ironic that a number of the proposed “solutions” in this article have been disparaged in the recent past as “hostile architecture” by the same individuals/institutions that are now advocating for them.

The problem is a pervasive (so-called) “progressive” ideology in SF — the bewildering refusal to acknowledge and insist that along with rights come responsibilities.

This ideological blind spot effectively countenances all manner of anti-social behaviors and allows them to fester.

To quote the renowned architect and urbanist, Leon Krier:

” (Traditional) architecture and urbanism is not an ideology, religion, or transcendental system. It cannot save lost souls or give meaning to empty lives. It is a body of knowledge and know-how allowing us to build practically, aesthetically, socially and economically satisfying cities and structures. Such structures do not ensure happiness but they certainly facilitate the pursuit of happiness for a large majority of people.”

That’s it, that’s all that architecture — on its best day; when implemented by knowledgable practitioners — is capable of.

I can’t claim deep familiarity with the full body of work introduced by Jane Jacobs, who is lifted up as a beacon of visionary urban design. For me and a generation of social justice and anti-displacement organizers & practitioners, we learned something fundamental: the people lead. Our understanding of what makes a neighborhood thrive comes not just from theory or design principles, but from the lived experiences, organizing, and collective imagination of those struggling to stay rooted in gentrifying and historically disinvested communities. Let me ground my comments with a broader community context/history, because design alone will not save the hood.

Both Casa Adelante and Fénix are powerful symbols of what it looks like when the people lead. Hundreds of local community members advocated and won significant public investments to get these buildings financed, approved, designed and built, after a 20-year stretch when no new affordable housing had been built.

Casa Adelante was preceded by a major open space and environmental justice victory, the creation of In Chan Kaajal Park, led by PODER, a Mission District–born organization. They took lead after an extensive popular-based grassroots planning process called the Peoples Plan (Mission Anti-Displacement Coalition), built around the slogan “they plan for profits, we plan for people”. City-owned lands were identified and prioritized as future affordable housing sites and green spaces. These two public sites were part of that 20 year vision.

At 1950 Mission, Anne Cervantes led a team of architects and CBO’s to carry out another piece of that vision which included affordable housing and community-serving businesses & organizations at a former school district site. Community members were engaged in creating this vision of a paseo artistico that would spill out onto Wiese Alley. It weaved a beautiful vision of providing free and reduced rate studios and gallery space for the neighborhood’s cultural creators, while providing art-based education and public activation for the neighborhood. The other two storefronts facing Mission St. were always envisioned as community-serving uses, like they are now.

And even with all the pressures the neighborhood faces, that paseo artistico vision remains alive. Youth Art Exchange has done an extraordinary job activating those art studios by offering City kids space and tools to explore music production, screen printing, fashion design, and more. It’s a living example of how community vision + organizing, not just design, keeps the soul of a place intact. And ultimately, that’s what it’s going to take to transform the conditions on our streets and begin to heal the trauma our communities are experiencing.

Very interesting, thank you for the nuanced perspective. As an FYI, some affordable housing sites (mostly PSH buildings) have 24-7 security at the front desk. Also, I hope these conversations inform the designers/developers of the 16th & Mission BART site (1979 Mission) across the street. I believe they are breaking ground in the Fall.

Walking through the Mission or Downtown area today, it’s impossible not to see the growing crisis of homelessness, drug addiction, and open use of substances like weed in public spaces. For many, this is more than just a city issue—it’s a daily reality that deeply affects the lives of everyday families and children trying to grow up in safe, healthy environments.

As a mother and a member of this community, it’s heartbreaking to witness young kids walking past people who are openly using drugs or passed out on sidewalks. Children absorb everything they see—they start to believe this is “normal” or even unavoidable. They might feel fear, confusion, or simply lose the sense of safety every child deserves in their own neighborhood.

For working parents and students who are doing their best to raise their children right, it becomes even harder when parks, public transport, or sidewalks become unpredictable or unsafe. Many parents are forced to make hard choices—like taking longer routes to school, avoiding public areas, or dealing with emotional trauma their kids experience after witnessing difficult scenes.

This post is not to blame, but to bring attention. Every life matters. And while those struggling with addiction need support and healing, we also need to talk about how it’s affecting the children who have no choice but to live, walk, and grow up around it.

Our city deserves healing—for the unhoused, for those fighting addiction, and for the families just trying to make it through another day. Let’s raise our voices for more mental health services, recovery programs, and safer spaces for our kids. Because they are watching—and they deserve better.