Every day, San Franciscans rise to roam the earth. They commute, stroll, and drive, most unaware that beneath their feet lie thousands of graves.

Beth Winegarner, Mission Local’s copy editor and a journalist, essayist, and author, met with this reporter to discuss the upcoming release of her new book: “San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries: A Buried History.” Set to release on August 28, it will be her seventh book.

Winegarner’s latest book, a combination of storytelling and investigative journalism, dives into the many cemeteries that ascribe San Francisco’s history. Winegarner discusses the burial, relocation and oversight of the city’s earliest cemeteries which, until recently, left thousands of the deceased forgotten.

We caught up with Winegarner to learn more about her research process, and what it means to honor San Francisco’s forgotten history.

How did the idea occur to you to write about this topic, which is so niche but full of substance?

I do have a strong relationship to the land — one of the reasons why I decided to start researching the cemeteries was that I’ve been living in San Francisco for close to 20 years, but I still felt slightly disconnected from it. So I started to research its history, and see what would really interest me. I’m very interested in what’s beneath the surface.

Then I wrote on the corpse roads, for Mission Local. It started with that research, and then I started writing. At some point I realized, I have to write a book, because there’s just too much interesting stuff here. And it just snowballed. I could not stop researching. So really, for every little thing, I’d think, “I wonder what else I can learn about this that will add more to the story?”

I noticed a great balance presented in your book, between investigative journalism and human narratives. How did you maintain that balance?

Well, human narratives, that’s sort of the key to journalism, isn’t it? You always want your central characters to inform the readers what the point of it all is. As a journalist, writing this book that was largely based on the journalism of the 19th century was really fun — going into newspaper archives and finding these old articles.

What was the most interesting aspect of looking at those old clips — what surprised you the most?

Even though most of the stories were written by white men, who definitely had their own agenda in doing so, for the most part they were accurate in what they were saying — you know, “We need to do a better job of relocating these cemeteries. Horrible things are happening; why is the city doing nothing about this?”

Are there any lessons that we can use for our future as a city?

It would be great if more places that looked at the possibility of relocating their dead could instead find a way to keep them where they are. I think that the less people are connected to those dead, the less likely they are to think very respectfully about it. I mean, these people were some of the earliest to live in San Francisco. Many of them were indigenous, who were here first.

We shouldn’t leave them behind in that way.

What were the challenges of researching something where there were so many gaps, with so many unmarked graves and unanswered questions? Did anything in particular bother you about that?

Many things have been lost over the years — for example, while I was researching City Cemetery up in Lincoln Park, I discovered that all the maps had been lost, as well as the records of people who were buried there. There was a brief period where I came across an inventory, which was done by the Daughters of the American Revolution, of thousands buried at Yerba Buena Cemetery.

I was excited to maybe do a project with all those names, until I realized that they had left many burials out of the record — those belonging to Chinese people, and probably other non-white ethnic groups as well. So I go forward with that, because it wouldn’t have been fair to leave others out.

In your book, you focus on the history and details of San Francisco’s cemeteries, but also the human experience of grieving and visiting loved ones. How did that occur to you, to include that personal aspect?

It’s something that I probably think about a lot, just because I love going to cemeteries. They’re a great place for reflection. I also like reading the names of people. Everybody has an interesting name. Sometimes I’ll see details on the gravestone about their lives, and it’s just a little snapshot of a person.

Throughout the book, I noticed a common trend. People were unhappy to be living near cemeteries, so no one took care of them. Thus, they worsened in condition, causing more strife among the unhappy residents. How do you think that pattern has shaped our cemeteries and history?

One of the things that’s funny is that San Francisco is all sand. So they [settlers] would dig these graves, and then the wind would blow the sand off the grave, maybe six months later, and it just kept happening.

I’ve never been in a cemetery where the graves were being exposed. So that would definitely make me want to improve them or talk to the city, to the caretakers of the cemetery.

You mention several times in your book that humans are “wonderfully contradictory” creatures, valuing their dead loved ones so intensely, but also at times, forgetting or disrespecting the dead. How do you think that nature affects our perspectives and past arguments surrounding San Francisco’s cemeteries?

Humans, in general, are great at finding whatever rationalization makes the most sense to them, and then sticking to it. You had people saying, “We don’t want to live next to cemeteries, let’s move them somewhere else.” You still had people with loved ones in those cemeteries saying, “We don’t want you to move our loved ones, we’re gonna sue the city.” So we need to find a way around this long standing taboo that we’ve had about digging up the dead.

What would you want someone’s biggest takeaway to be from reading your book?

Hmm. There’s so many. I would love for people to be more curious about their environments, wherever they happen to be living. San Francisco is a place where there are not a lot of inhabitants that are native to the land. People come and go. I would love for people who live here, for even just a year or two, to become more curious. It’s a grim topic, but it’s very interesting.

Where can those curious readers find your book?

The print book is available for pre-order now. There will be an e-book version that should be available on the publication date. It should be in bookstores in the Mission, like Dog-Eared Books.

Readers can check out Winegarner’s site for more information on San Francisco’s buried history, as well as other books, essays, and works by Winegarner.

Ex-cabbie here. Once was flagged by a newly-enrolled student at USF on her way to the Lone Mountain campus. Making conversation, asked her if she knew that the campus was the the former location of Lone Mountain… cemetery! She laughed and said that not only was she aware of it but that– during orientation, no less!– if she happened to be in the building after dark, to not be surprised to hear things “that go bump in the

night” which I thought was very cool– and very “San Francisco.” (Seems there was a time in San Francisco when what wasn’t brothels was cemeteries and everything west of Laurel Heights, and what is now Masonic Avenue, was cemeteries then sand dunes. I still refer to the area between California and Fulton Streets as “Cemetery Ridge.” Back-story of the movie POLTERGEIST resonated with me.)

I look forward to adding your collection of stories to my bookshelf.

Thanks, Walter!

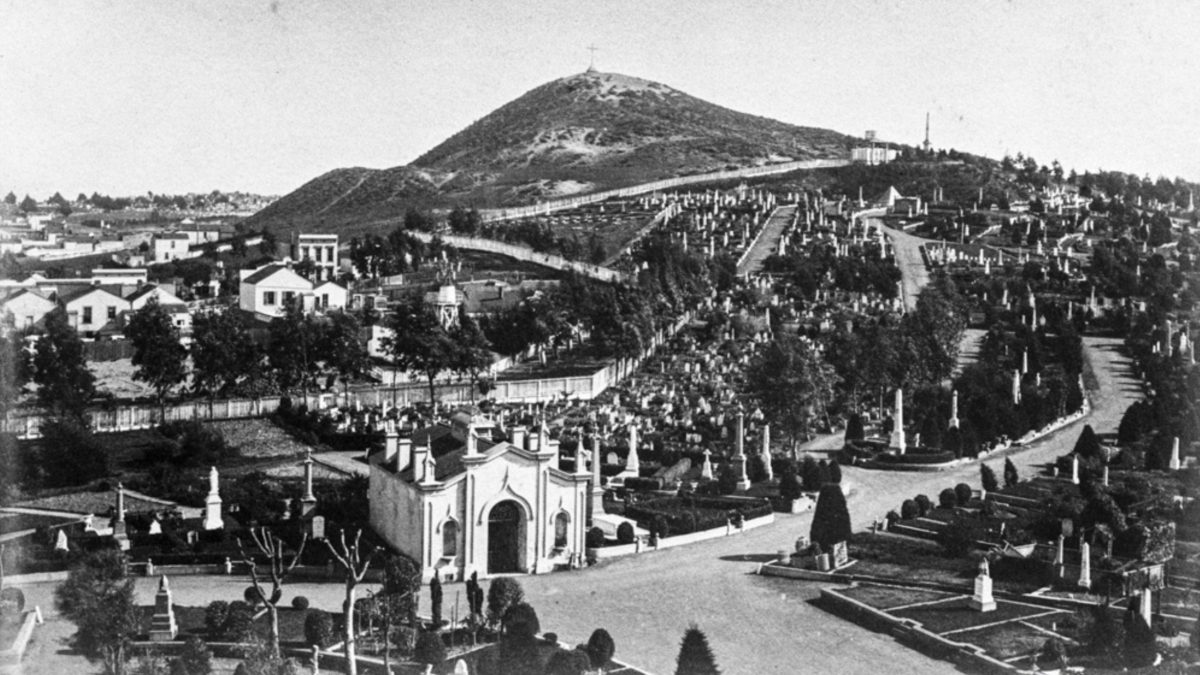

The Lone Mountain pic at top (Odd Fellows Cemetery) dates to just after the burial of the little girl who was discovered in the Richmond some years back. She’s in that pic somewhere, holding a single rose.

Indeed. She’s in the book!

Awesome. Cemeteries tell so many tales and invoke so many emotions, I can see why you became enthralled. Nicely done!

Oh this is two years old! I’ll look for this book, love this topic. I’m a big fan of the Columbarium.

To the author’s point, “ San Francisco is a place where there are not a lot of inhabitants that are native to the land. People come and go. I would love for people who live here, for even just a year or two, to become more curious.”, I say we all consider the effect of WWI; WWII. For example, my great-great grandparents traveled to SF to work on the GG Bridge after finishing the Sydney Harbor Bridge in Australia (my family were Scottish/Irish/Dutch in heritage skilled in iron and bronze works). My grandfather was born in SF and grew up not far from The Mission on Treat St. at 1563 Treat St. close to the dead end up past Precita Park before he was enlisted into the Navy. His father lived across the street at 1578 Treat St. Once great-great grandpa died my family moved into Cole Valley.

So, to say “…so many inhabitants come and go…”, Ha’s the author considered each San Franciscan per her understanding just doesn’t know their heritage? I know many families who have been property owners in SF since BEFORE the First World War and even predating 1900. They are still here. Raising their children. Living in their multi-family homes rebuilt after the first quake. Living out their lives happily. Just as I am doing since my family migrated from AU to work on the Golden Gate Bridge. Yes, lots of temporary transient members of SF come and go. But many more are surviving inhabitants to the land than you would think although hardly any of us are Ohlone.

Fascinating topic for a book, especially for those interested in local California Bay Area family history. QUESTION: I am unclear on the news story about the book…Does the author say they deliberately left certain (hard to find) cemetery names and information out of the book “to be fair” because it did not include Chinese and other ethnic people from back in time? Or is it included, but she mentions there still needs to be much more investigation into many others whose names have not been found/included?

Debra, there was never a plan to include the names of all of the Yerba Buena dead (or any from other cemeteries) in the book. But if you’d like to see the DAR records for Yerba Buena and other cemeteries between 1848 and 1863, they are available online in several places. Here’s one: https://archive.org/details/sanfranciscoceme00daug