Brenda Storey, the executive director of the Mission Neighborhood Health Center turns over a piece of paper, draws a square and breaks it up with oddly shaped lines.

“This is how we cover care for our patients,” she says. “It’s a puzzle with 22 pieces or funding sources.”

Talk to Storey for more than 15 minutes and solving the puzzle to treat 12,000 patients a year—67 percent of whom are uninsured—begins to feel more like a sci-fi video game in which puzzle parts shrink, grow with the federal stimulus only to shrink again. The governor’s state budget proposal would zap two pieces altogether—one that treats children and another that treats low-income adults.

“I don’t think we have ever here before,” said Storey who has worked at the center for 25 years, 15 of those as its executive director. “I don’t remember a time when things were this bad. Now it’s like everything is being cut.”

For one brief moment this spring, the future looked manageable. Sure the city rolled back a primary care grant by $52,500 in January, but in March, the Federal stimulus package—billed as the largest social spending program in history— delivered $328,00 over two years to Storey’s door. Relief. And, extended hours.

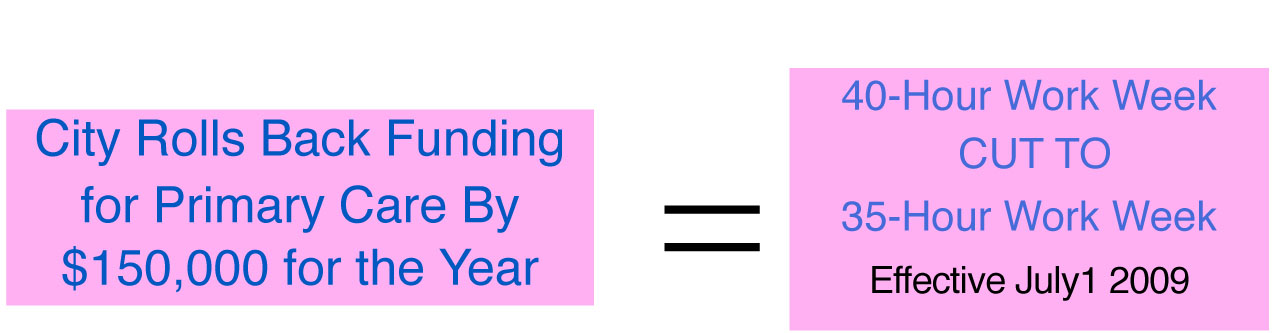

Then, it became clear that the city’s roll back would become $150,000 for the full year and that meant cutting staff hours by an hour a day and staggering shifts so that the center could continue its normal hours and the expanded hours the stimulus grant funded.

This summer as the San Francisco faces a $438 million deficit and the state’s budget deficit has reached $24 billion for the year, Storey and other community clinic directors got news that they could face even more dramatic changes in service. “I’m not hearing much encouragement from representatives,” she said. “Everyone is looking at this grimly. People are in shock about the enormity of it.” .

Dick Hodgson, the vice president of policy and planning for the San Francisco Community Clinic Consortium, a group of 10 city clinics that serve more than 70,000 patients said, “Some of these places are not going to be able to survive.”

Hodgson declined to names the most vulnerable clinics, but added that Storey’s clinic was not one of them.

However, in addition to reducing the hours for the full time staff, Storey’s outreach program to test Latino men for HIV/AIDS will lose one part-time worker and the full-time worker will go to 75 percent time.

Latino men, Storey said, are late testers, a condition the clinic was trying to change because testing late means a more advanced disease and that means more expensive care.

But, those cuts will seem minor if the state assembly approves Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s proposals to end Healthy Families or cut funds for Early Access to Primary Care.

For every dollar the state spends on Healthy Families, California’s version of the Child Health Care Program, the federal government puts in $2. If the governor ends state funding, the federal funds disappear as well.

Some 12,000 San Francisco children are covered by Healthy Families, 900 of them in the Mission District and 500 of those at the Mission Neighborhood Health Clinic. Ending Healthy Families, said Storey, means another $150,000 cut. But, she pointed out, all over the city, clinics and the children they serve would be severely hit.

The California Budget Project released an analysis last week that concluded children would be “disproportionately” affected. Education, Calworks, Child Welfare are among the programs that could be affected. “I think about all of the other cuts,” said Storey. “The ability of teens to get money for college…”

She looks down at her puzzle.

The governor has also proposed cutting Early Access to Primary Care. His $34 million statewide, means $274,524 at the Mission clinic. In terms of patients, the money treats 1,466 adult patients for 4,400 visits.

Another piece of the puzzle has vanished.

To read more about how individual cuts will impact San Francisco and other counties, go to the California Budget Project.

Click on the image below for a full view.