The San Francisco Poster Syndicate was busy this year.

A collective of some 20 active screen-printing artists, the syndicate was everywhere: at Civic Center to protest President Donald Trump’s inauguration, at Dolores Park for the “No Kings” protest, at Balboa High School for San Francisco teachers’ near-unanimous strike vote, and at dozens of other actions across the city.

They gather in the back of the crowd and roll up their sleeves for “live” printing. They lift and lower a metal screen, and push ink through a stenciled design made by syndicate members, and repeat.

In 2025, the syndicate distributed at least 10,000 free posters, an estimate based on the amount of paper used.

“People are always surprised. ‘Oh, it’s free? Do I need to pay for it or something?’” said Logan, an artist with the syndicate. “But we are doing this in community, for the community. It feels like we’re putting out there the world we want to see. Not everything has to be about money.”

The goal, Logan said, is that “if we make something beautiful, you may want to hang it on your fridge.”

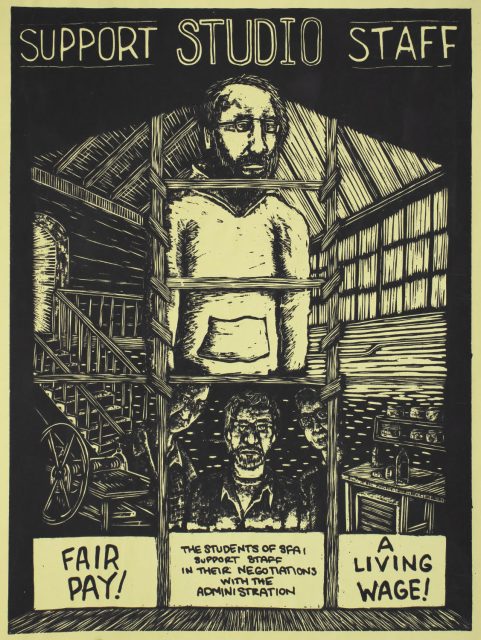

The San Francisco Poster Syndicate started in 2014, when adjunct instructors at San Francisco Art Institute were forming a union. Art Hazelwood, one of the syndicate’s founding members, taught screen-printing there and was part of the bargaining team.

He and his students started printing posters using salvaged “slop ink” — everything leftover from a day of art classes, mixed together in a bucket — and put them all over campus. The posters of that era were all gray, Hazelwood, now 64, recalls.

Hazelwood and other artists kept on making posters for student and faculty issues, and collaborating with unions across the Bay Area.

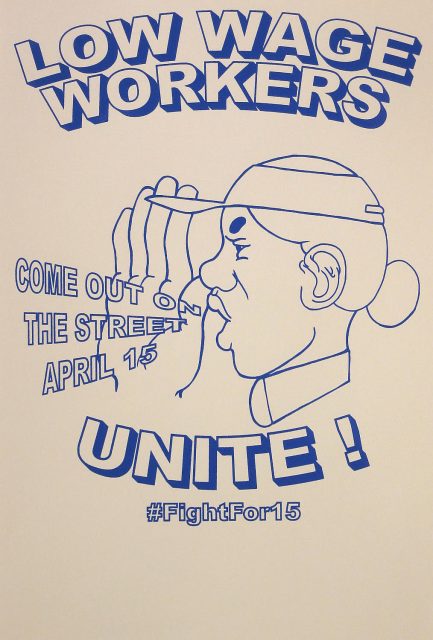

In 2016, the syndicate became involved with the “Fight for $15” campaign to raise the minimum wage in San Francisco. Hazelwood brought in fast-food workers to talk with students, who came up with designs based on their working conditions and demands.

The process became the syndicate’s model for working with other movements.

“We were not trying to impose our views,” Hazelwood said, “but work with different groups to put a graphic face on what they’re fighting for.” That movement set another precedent: The group began printing posters on the streets for the first time.

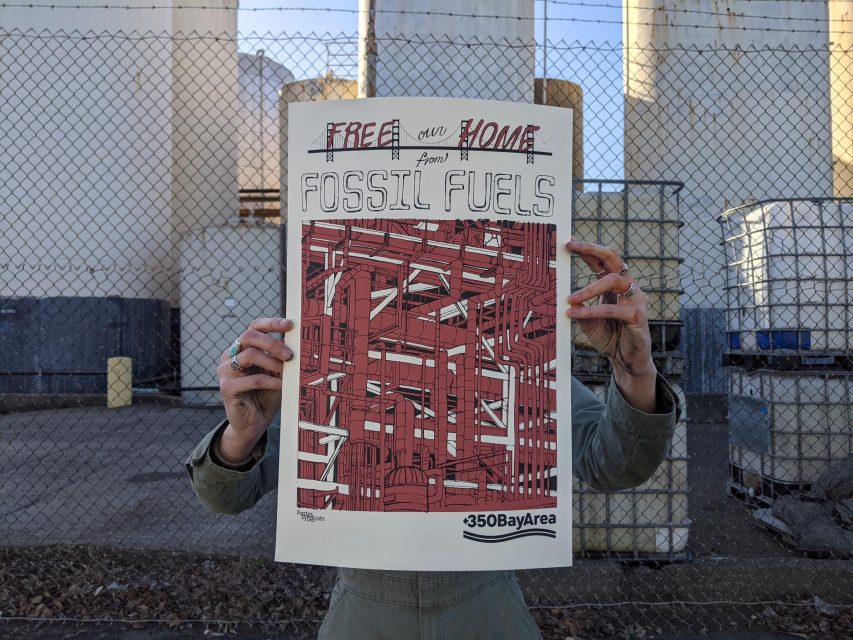

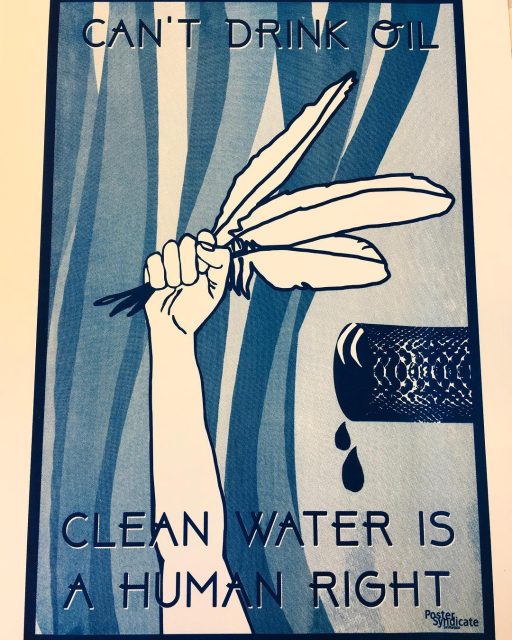

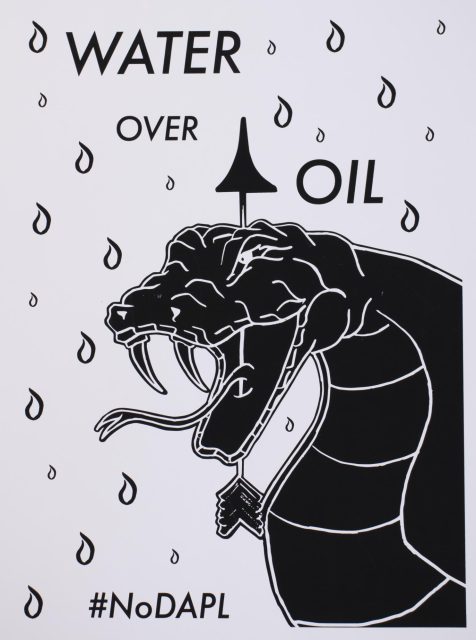

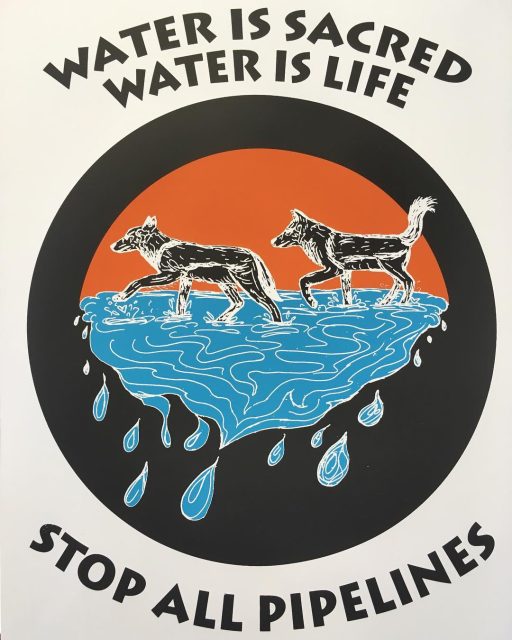

After that, it was out of the print studio and into the streets. That November, the syndicate printed posters that read, “Water is sacred. Water is life” and “Can’t drink oil. Clean water is a human right,” rallying against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Civic Center Plaza.

They printed posters protesting Trump’s first inauguration, and then the second. In a change of medium, they created protest murals on Clarion Alley.

Logan, 35, first encountered the syndicate at a “Protect the Vote” protest in November 2020.

As a graphic designer, Logan was fascinated, but there was no time for chit-chat. Only three people were printing that day, with a long line of people waiting for posters.

“Get an apron,” Hazelwood said, seeing Logan’s interest. “Help us do it.”

That kind of invitation is not unusual. Last year, when the group was printing in front of City Hall as the Supreme Court heard the Grants Pass case, which would decide whether cities can punish people for sleeping outside, a bridesmaid volunteered to help. She threw an apron over her dress and got to work.

“We’re kind of a street theater,” said Hazelwood, “because the posters have more value when people see them being made.”

It invites conversation. Logan compared making posters to being at a party: “Sometimes you’re the type of person holding a drink. Or you can be the one helping clean or set up,” she said. “I’ve actually had more conversations making posters with people at a protest than being at a protest.”

Those interactions are “addicting,” Hazelwood added. “It’s modeling kind of an ideal society where not everything is transactional.”

None of the posters are credited to a single artist. That protects members from prying eyes, like those of university leadership or the Trump administration’s surveillance on political dissent.

Every poster is a collective effort: Different members might create a design, do a drawing, or, at the action day, take on the physical work of printing. When people ask who made a poster, “the syndicate made it” is always the answer.

The posters have come to document a history of Bay Area movements.

“The people who do the actual fighting on the street, the actual activists, they disappear,” said Hazelwood. “The posters become the symbol of what was done.”

The history-making is in rapid swing today.

“If you think about where we were at the beginning, when everybody was caving in, and where we are now, where people are fighting back,” Hazelwood said. “It’s a great time to make posters.”

Thank you to these artists doing a wonderful community service for Bay Area protesters! No, they don’t support all causes equally- who does that?! And no, they don’t single-handedly have the power to remove a president from office. But, as history shows, mass participation in nonviolent movements (with signs!) is an effective way to challenge authoritarian regimes & defeat dictatorships. We need more community, not haters.

“No, they don’t support all causes equally”

OK, so then who gets to decide which causes are worthy, and which are not? What are the criteria for a protest to be considered the right kind of protest?

Grassroots art collectives aren’t public utilities and they aren’t obligated to be “ideologically neutral.” They’re artists and volunteers choosing to donate their time, skills, and materials to causes they believe in.

That’s not censorship, that’s freedom of expression.

Every artist, printer, writer, and musician has always made choices about what they support. No one demands that bands play every rally, or that painters accept every commission, or that newspapers print every opinion.

If a collective chooses to support protests aligned with their values, that’s exactly how grassroots movements have worked throughout history, from civil rights to labor rights to anti-war movements.

The expectation that volunteer artists must provide equal support to causes they don’t agree with isn’t a defense of free speech, it’s an attempt to police it.

Support what you believe in, create what you stand for, and let others do the same.

Does the Collective make posters for any and every protest, no matter what the subject?

Or is there some kind of ideological vetting process that ensures that only the “right” kind of protest gets this free illustrative help and support?

A rhetorical question no doubt. Based on the numerous samples we see, it would appear they only make posters for ideologically correct protests.

Exactly, sman, there is no transparency about how they decide which causes are politically correct. It is just a fairly blatant attempt to skew public debate in an arbitrary manner.

Those blindly supporting this kind of message distortion will soon change their tune when the supported cause is one they don’t like.

Their posters are so effective! They did a great job in knocking Donald Trump right out of office! Thanks to them, we now have a different President!

Change is slow hard work. Just because it did not topple a president doesn’t mean it did nothing.