When the Covid-19 pandemic hit San Francisco five years ago, perhaps no neighborhood was hit harder than the Mission. Social distancing wasn’t an option: People had to go to work. In the early months, Mission District had the highest number of confirmed Covid cases, and the fourth-highest rate of infection.

To the rescue: the Latino Task Force, a coalition of three dozen community-based organizations. It consisted of Latino activists, many of them women with deep roots in the community.

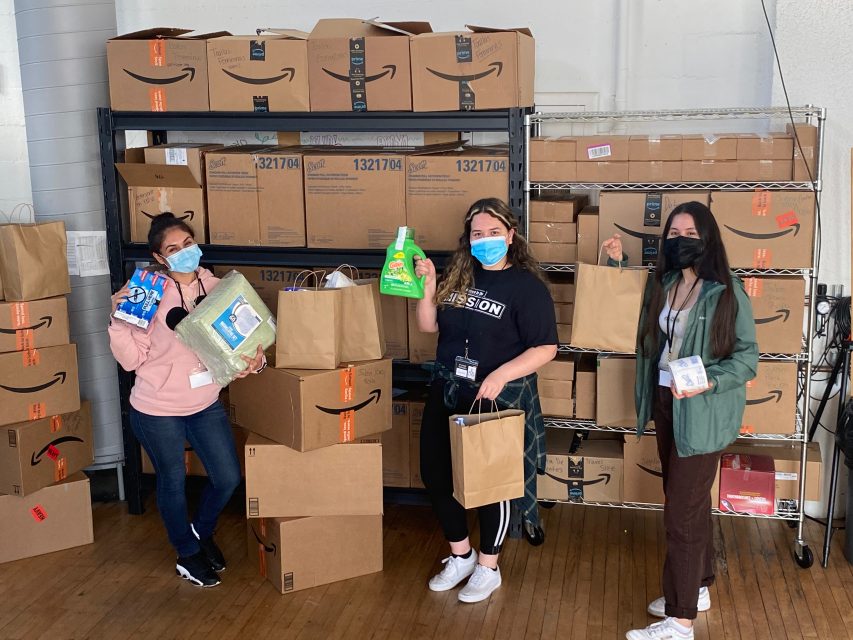

They handed out boxes and boxes of food from a truck on Alabama Street. They set up a resource hub to offer help with housing, employment and medical care. They sent volunteers door to door to persuade Mission residents to participate in a Covid testing study.

This month, the fifth anniversary of the Latino Task Force, the coalition’s leaders are starting to pass the torch to the next generation of activists, some of whom are their own daughters and mentees.

“If we could create enough leaders and put them in places all over the city,” said Tracy Brown, a member of the task force’s executive committee and a veteran activist, “they would come with that value of helping others, uplifting community, and working to give women more power and voice in decision-making everywhere in the city.”

That includes Katia Padilla, 31. Padilla was star-struck when she first interviewed for an internship at Latino Task Force in its early days with Brown.

“I had never seen somebody who looked like me, someone who spoke like me, came from communities I came from, but in a position with such great power, knowledge and influence,” Padilla recalled.

She got the internship in 2021, writing press releases and advocating for funding with city departments. After working on and off for the coalition over the years, Padilla was hired this February as its chief operating officer.

“It’s amazing, because I’ve gotten to see it grow into what it is today,” she said. She hopes that it continues to grow, and “that we don’t get stuck in a place of lack.”

“Lack” is all too familiar to Padilla, who first confronted it as an intern studying the coalition’s budget. “We do the work in the community that the city pays us to do because they can’t do it, so they’re contracting us to do it. Why does this process feel like we’re begging?” she thought.

Now, through advocacy, Padilla wants to change that. Her hope is that the task force survives “in the way that we no longer have to beg for the funding,” she said. “I’m going to make sure that people know who we are. That’s my job.”

‘Daughters of Mission Girls leaders‘

Many of the young activists at Latino Task Force grew up in Mission Girls, a women-led youth service program that provides activities and space for at-risk girls. The program started around 1988, predating the pandemic by decades. It was there, many said, that they first learned how to speak up and be a leader.

“They knew what a good program looks like, because they had experienced that,” said Brown, who founded Mission Girls.

For Estefania Lopez, her first day involved with Latino Task Force recalled being a 6th grader at Mission Girls. Her best friend, who she met at Mission Girls, introduced her to a job as a program coordinator at Mission Language and Vocational School.

in the spacious two-story building on Alabama Street, kids from summer programs were running around everywhere. When Lopez was introduced to people, she recognized them from Mission Girls.

“I’m almost back at Mission Girls. It felt like that, just 10 times bigger,” she said. “I used to just run around, but now I run around to make sure things are good.”

At Mission Girls, Lopez recalled, the leadership was all women of color; people who looked like her, talked like her. “I look up to them as parental figures.” she said.

Today Lopez, 30, works as a manager of education and career pathways at the Bay Area Community Resources, running job readiness training programs to help Spanish-speaking and undocumented youth.

“I always felt inspired to try and do half of what the leaders in my life had done,” Lopez said. “It’s just crazy because now you’re invited to the table and in conversations with other community leaders that you saw growing up.”

When Alondra Gallardo thinks of her time at Mission Girls around 2003, she remembers the poetry, the dance and cooking classes, and field trips in the summer.

Above all, she loved the warm, safe feeling the program created. A “timid kid” back then, she got to speak on different topics and explore her own interests, “in a safe space to engage in those activities without feeling a sense of judgment.”

Gallardo is the niece of Brown, who founded Mission Girls and still serves on the Latino Task Force’s executive committee.

Growing up with Brown by her side, as family and as neighbor, Gallardo felt taken care of: Brown made sure Gallardo, the first-generation daughter of two Mexican immigrants, knew how to tap resources that her parents didn’t know about. It was Brown who told Gallardo about scholarships and other support when she was applying to college.

Now 29, Gallardo, director of the coalition’s resource hub, wants to take care of others in the community, too.

She started as a food volunteer in the summer of 2020, when the task force was providing meals to upwards of 700 families. On the July 4 weekend, Gallardo recalled, the line curved around the blocks from 19th and Alabama streets to San Francisco General Hospital. Gallardo managed the lines, distributed tickets and kept track of the number of meals given away.

She’s had “a lot of blessings in my life and my upbringing,” Gallardo said. “I want to be able to give back what I was able to receive.”

But she also wanted to give back something more, “needs that were not spoken about in my parents’ generation,” she said.

Mental health is one of those needs. People who come to Latino Task Force for help are often embarrassed because they’ve never had to rely on government programs or community services, she said.

Gallardo, who has a psychology degree, tries to offer help discreetly “when folks are not comfortable sharing anything.” What’s important, she said, is “knowing when it’s too much to pry from folks, and knowing also how to communicate and meet them in a different way without necessarily having to speak out loud.”

Like Gallardo, Tatiana Hernandez, daughter of Joanna Hernandez, co-chair of Latino Task Force’s reentry committee, feels she was “born into the community.”

“I’m always known as Joanna Hernandez’s daughter,” she said. “Sometimes people forget my name is Tatiana Hernandez and I want to make my own way. My own name out here, my own stamp in this community.”

Tatiana started working at Latino Task Force’s students hub, a program for unhoused and undocumented kids founded by her friend Mariela Gallardo, Brown’s daughter.

Operating out of the Mission Language and Vocational School building, they organized after-school activities, P.E. at local parks, and field trips to Six Flags — “places these kids have never been,” Tatiana said.

In 2023, Tatiana took a break from working with kids and went to a barber school. She and Joanna later created Freedom Braiders, a program to teach incarcerated women in San Francisco County Jail to braid hair, a skill “they can take with them wherever their journey takes them.”

The mother-daughter duo gathered nine well-known braiders from the Bay Area — those who have braided hair for celebrities like rappers, football players and artists — to teach a cohort of 16 women at the jail. They brought in doll heads, gel and rubber bands.

“Yes, there was laughing and braiding, but at the end, it was about bringing these ladies together who are inside. My mom says it really well: The lights stay on 24/7, but it’s still a dark place,” Tatiana said.

‘There are still fires‘

When the Latino Task Force was created in the spring of 2020, the mission was simple and urgent: Get people tested. Feed them. Help them find a job.

“Now, there are still fires,” Lopez said, just “not as big as they were before.”

With the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigration, the activists at Latino Task Force, young and old, are working to protect immigrants in the Mission through “Know your rights” training, tax services, job resources and more.

Padilla, the task force’s newly appointed chief operating officer, is leading the annual May Day march, an event that feels especially difficult this year, she said.

“It’s a little overwhelming to think about making our people go out and march in a country where you’re second-guessing whether this is a real free country, where you get to say what you think,” Padilla said.

Still, the march is going ahead.

“A lot of us are still scared, but we’re doing it,” she said. It’s better knowing that “we did the best that we could for our people, than giving up and not doing a thing.”

Can the reporter please mention that the Zia symbol pictured on the clothing in the first image is the Zia symbol from New Mexico and originated from the Zia Pueblo tribe.

I doubt the Latino task force has asked or paid to use the Zia Pueblo of New Mexico’s logo for the Latino task force’s monetary gain.

Great article about great ladies. They should feel proud of the services they fulfill for their community.