It’s possible to have a lifetime of exposure to the famed painter Édouard Manet yet be largely unaware of the equally talented Berthe Morisot, the Impressionist painter intertwined with him from virtually every angle: as colleague, inspiration, model, customer — and even sister-in-law, after Morisot married Manet’s brother, Eugène Manet, a move that allowed her to continue to work as an artist.

It all makes the new exhibition at the Legion of Honor, “Manet & Morisot,” that much more compelling. The show, opening Oct. 11, will give museumgoers the opportunity for the first time to understand how deeply the two French painters were in conversation with one another.

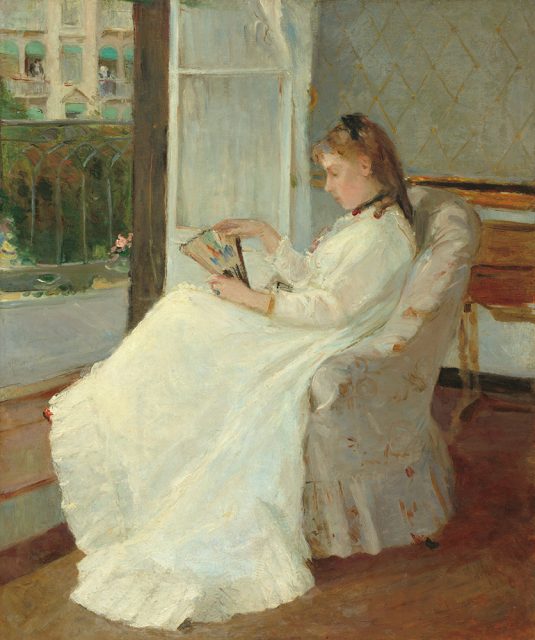

The show opens with Manet’s “The Balcony” (1868-69) hanging alongside Morisot’s “Young Woman at Her Window” (1869), a pairing with echoing terraces. That Morisot was restricted by her status as a woman in 19th-century France is reflected in the two artists’ perspectives. While Manet paints figures from street level looking in — including his first depiction of Morisot, who sat for the painting accompanied by a chaperone — Morisot flips Manet’s perspective to portray a woman from the inside looking out.

“She was someone who was seen by her contemporaries as essentially belonging to the private sphere, the domestic sphere,” said Emily A. Beeny, chief curator of the Legion of Honor. “We have a sense of the way in which her world is circumscribed.”

Manet himself belittled that world after first meeting Morisot and her sister, both painters, at the Musée du Louvre. He wrote of the encounter: “It’s a bother they’re not men, but as women, they could still serve the cause of painting by marrying an academician each and sowing discord in the dotards’ camp.” Despite the off-color joke, the two artists would go on to have a collaborative — and familial — relationship that respected Morisot as a painter in her own right.

The artists have their distinctive styles, which are particularly apparent in their twinned depictions of the same slice of Paris just five years apart. Morisot’s “View of Paris from the Trocadero” (1871-72) shows off her skill as a landscape painter and her particular facility in depicting clouds and light, whereas Manet’s “View of the Exposition Universelle” (1867) depicts “life as a stage set, a pretext for these vividly observed figures,” Beeny said.

While Morisot initially looked to Manet for approval and inspiration, later on it’s Manet who borrows from Morisot. He took inspiration from her for the composition of his most famous canvas from the 1870s, “The Railway” (1872-73) by placing a female figure with her back to the viewer — a technique Morisot had already used in 1871.

“It’s an idea that may have come to Morisot from contemporary fashion plates,” said Beeny, “where little girls often turn their backs to us to show off bows and bustles.”

Yet in gazing at the young girl turned away and gripping the bars of a fence, it’s hard not to think of something else entirely. Those full skirts, made even heavier with elaborate bows — just like the fence that looks eerily like a cage — could also symbolize the imprisonment of girlhood.

In the latter part of the exhibition, both artists’ brushstrokes become looser, and the technique of the two painters align so much as to look nearly indistinguishable. They become metaphorical and literal mirrors: Manet’s “Before the Mirror” (1877) hangs beside Morisot’s eerily similar “Woman at Her Toilette” (1879-80). For Morisot, the looser strokes are likely a time-saving measure after the birth of her daughter, Julie Manet: She has to work efficiently in short bursts, Beeny said. As for Manet, who never joined the Impressionist group but always wanted to be understood as its father, he may be trying to imitate Morisot’s freer look.

Perhaps the most satisfying grouping in the exhibition is the uniting of Manet’s and Morisot’s portrayals of the four seasons, a first-ever occurrence: Manet’s “Spring” and “Autumn” (1881) are hung alongside Morisot’s “Summer” (1878) and “Winter” (1880).

Often mistaken as Manet’s pupil or understood only as the subject of Manet’s portraits, Morisot claims her proper place with her 1885 self-portrait at the end of the exhibition. Painted shortly after Monet’s death, the work is “superb, confident and almost defiant,” said Beeny, noting her dress looks nearly like a military uniform replete with insignia. In contrast to so many of her other depictions of women, there are no bows or frills in sight.

“We wanted to hang this here so you could look at this painting and look across the way at ‘The Balcony,’ Beeny said, “to think about the distance Morisot has traversed.”

“Manet & Morisot”

Oct. 11 through March 26, 2026

Legion of Honor Museum

Great piece, thank you! The FAMSF magazine’s write-up of this exhibition was good, but I think I got more info here, thanks Ms. Zigoris and ML!