In San Francisco, “What ballot proposition comes after Prop. Z?” is not a hypothetical question. We’ve done this: It’s Prop. AA. And, after that: Prop. BB.

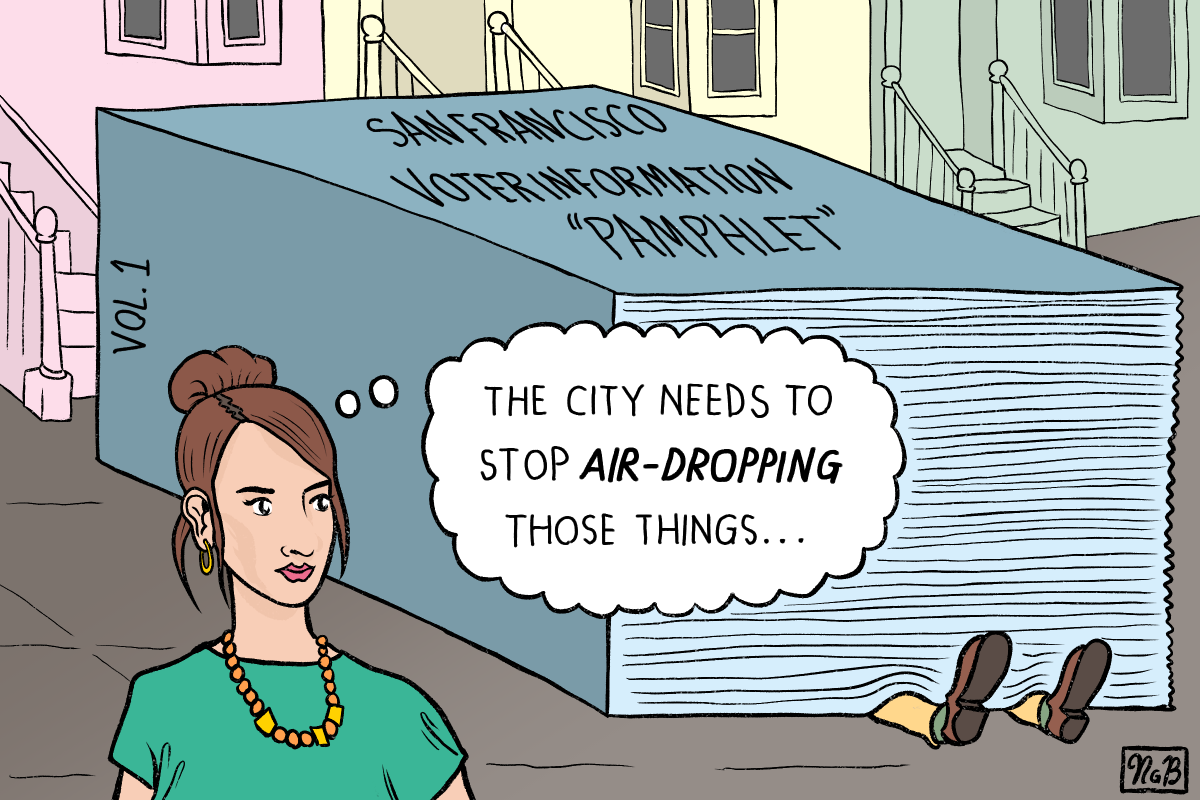

Exhausting the alphabet is not a yearly occurrence; it is to San Francisco ballots what 1906 and 1989 were to San Francisco earthquakes. But tremors are always a part of life here, as are obnoxiously large ballots. As recently as November 2016, the Voter Information Pamphlet was 313 pages long, which seriously stretches the definition of the word “pamphlet.”

In that year, when San Franciscans voted on 25 measures, I wrote about the phenomena of San Francisco’s gargantuan ballots with the plight of the city’s put-upon letter carriers as a framing device. A mailman named Daniel Biasbas told me that, when Voter Information “Pamphlets” exceed 200 pages, he can no longer fit them in his satchel, and must park and repark his mail truck three or more times on each block of his route. He claimed that oversized voter material led to a fellow mailman going out on worker’s comp.

American democracy is fragile. But, in San Francisco, it’s also burdensome — to voters and letter carriers alike.

This year, San Franciscans will be voting on only 15 or so ballot measures. The ludicrous sums of money pervading local elections, however, could well translate into ludicrous amounts of paid ballot arguments. That could push this year’s voter guide north of 200 pages, to the chagrin of Biasbas and his colleagues.

What’s also ludicrous is that, to habitually overburdened San Francisco voters, 15 ballot measures doesn’t seem like quite so many. But it is: In Oakland, voters will weigh in on three city measures.

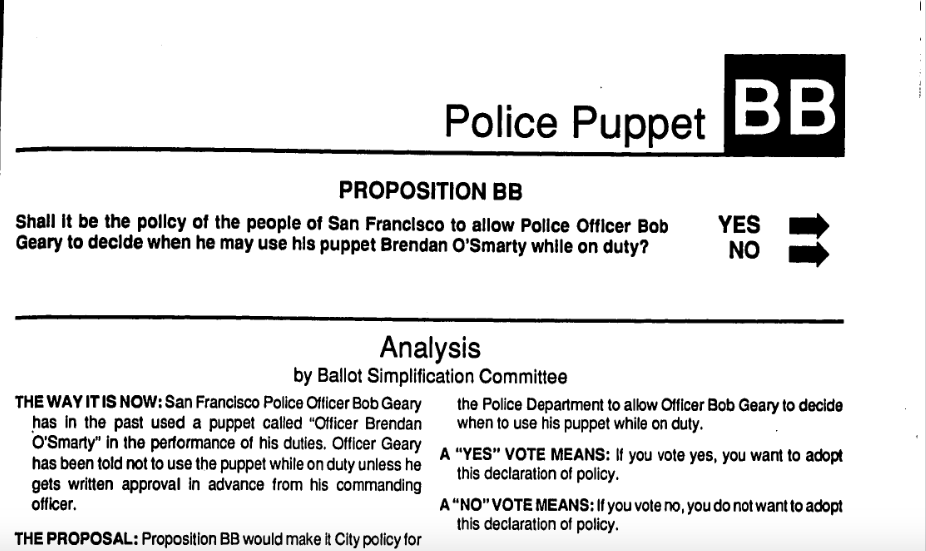

San Franciscans, quite simply, vote on more stuff. We vote on more stuff than anyone, anywhere. A perusal of past ballot measures reveals that plenty of them are bizarre, silly, arcane stuff — with the apotheosis surely coming in 1993, when a slim majority of city voters approved Officer Bob Geary being able to walk the beat with his ventriloquist’s dummy, Officer Brendan O’Smarty. Geary gathered 9,964 signatures to get this measure before voters. It was given the designation “Police Puppet” and was the 28th measure on the ballot: Prop. BB.

But a lot of the stuff we vote on is neither bizarre, silly nor arcane — or, even if it is, it’s still costly, consequential and far-reaching. This year, tucked into the periphery of a voluminous ballot, voters will decide whether to radically remake the City Charter, heavily alter our business tax structure (the legal text of this measure exceeds 100 pages), make hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of pension commitments, and devote millions to set-asides, even as San Francisco’s budget prospectus grows dimmer and dimmer.

It goes without saying that this is all but certainly not top of mind for you or any other city voter. We’re also voting on a slew of state measures, supervisor races, citywide offices, a charged and contested mayor’s race and, overshadowing everything, an epochal presidential contest featuring Donald Trump and erstwhile San Franciscan Kamala Harris.

But, regardless of who wins those higher-profile contests, the ramifications of our many ballot measures linger for years. They always do. There are consequences of running your government this way: Alterations to the city charter can only come via a vote of the people and, subsequently, can only be corrected or altered by a vote of the people. Like plastic surgery or trimming your sideburns, once you start, you can’t stop.

San Francisco excels at politics, but struggles with governing. In loading up our ballot with propositions that are often spawned by special interests and then lavishly funded by those special interests — and carried by politicians hoping to set the political agenda and/or achieve higher office — the city is effectively substituting politics for governing.

There are consequences to this after the dust settles on Election Day, and we live with them until we do it all again on the next Election Day. Why are our elected leaders so eager to toss items onto the ballot? There are a number of reasons, and we’ll get to them. But, at its core, it’s the same reason your dog licks its own private parts.

They do it because they can.

Longtime Bay Area political scientist Corey Cook, now the provost at St. Mary’s College, recently returned from a sojourn in Idaho. In that state, “the idea of qualifying stuff for the ballot is like putting a man on the moon.”

In San Francisco, it’s more like putting a man on Half Dome. Not only does it happen all the time, it’s the subject of entire cottage industries. Ballot measures here are so common, Cook continues, that the actual professed goal of the ballot measure is often wholly superfluous. The real goal could simply be using the ballot measure — which, unlike a candidate, can take unlimited donations — as fundraising vehicle. Or it could simply be a means of introducing ideas into the political discourse to achieve larger goals.

“The ballot becomes the process,” says Cook, “not the outcome.” In San Francisco, he continues, “the role of political entrepreneurs to define the agenda is profound.”

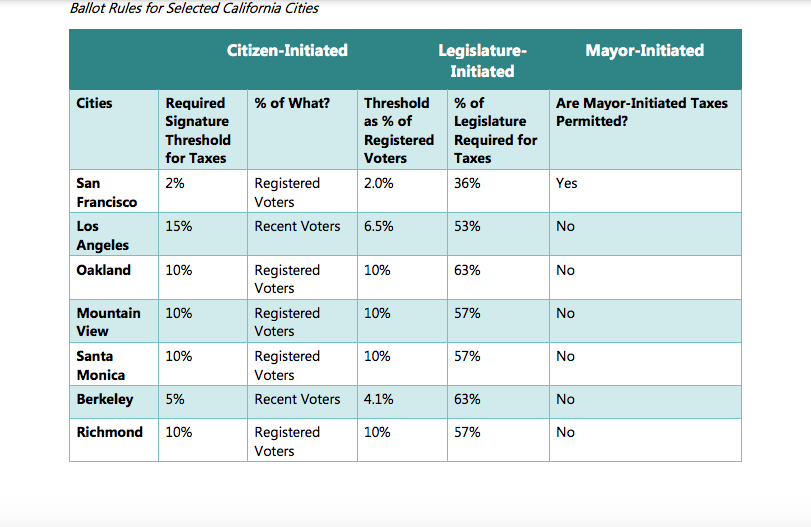

We enable all of this because the barrier of entry to San Francisco’s ballot is very, very low. The mayor can unilaterally place items on the ballot. It requires only four supervisors to qualify a ballot measure. San Francisco requires a far lower percentage of the electorate than anywhere else in the state to provide signatures to place items on the ballot and, to boot, is more generous in providing the time to gather those signatures. Recalls are especially easy to qualify here.

“We have surveyed on this,” says former longtime controller Ben Rosenfield. “The ability to place a lot of laws directly on the ballot without going through the legislative process is truly unique to San Francisco.”

In short: They do it because they can. And it turns out that you can have too much of a good thing: Think of Bob McKenzie nearly drowning in beer in “Strange Brew.” San Franciscans, meanwhile, are drowning in democracy. At some point, even the most diligent voter runs out of oxygen. And, while this year’s ballot is not large by this city’s perverse standards, there is so much more than usual to be distracted by.

Have San Francisco’s ballots grown so large that they in essence overwhelm democracy? Is there a limit on how big a ballot can be before voters are rendered numb? “Clearly, we have exceeded it, at times,” says former longtime controller Ed Harrington. “One imagines it’s more common to vote on five things, seven things. Not 20. Not 28.”

San Francisco, again, excels at politics and struggles with governing. Governing is hard; the deliberative back-and-forth to reach compromise is hard; producing well-written and functional laws is hard. It’s not nearly as hard to push material onto the ballot that may not be well-written at all and is replete with unintended — or intended — consequences lurking within its lengthy word salad.

Governing, again, is hard. It’s not nearly as hard to make everything into a partisan issue and short-circuit the deliberative process with a ballot measure — which you can present to your partisan backers as a cudgel with which to pummel their political foes. And you can fund-raise off of it!

This can lead to the commonplace San Francisco eventuality of competing ballot measures. After all, why build one when you can have two at twice the price?

It’s suboptimal to govern this way, though. San Francisco is Exhibit A of that. And this has long been the critique of direct democracy. As far back as 1939, political scientists V.O. Key and Winston Crouch declared the ballot initiative process as “deficient as a legislative device in that there is no opportunity in the process of formulation of a measure for its opponents to be heard.”

Key and Crouch, however, were focusing on governing, not politics. It’d be generous to assume that the powers that be in San Francisco are doing the same.

Both Rosenfield and Harrington contributed to a report on how to better govern San Francisco published by SPUR last week, which dutifully highlighted the low barrier to the city’s ballot. This follows many other reports offering recommendations and reforms on how to better govern San Francisco. The city could do worse than enacting these recommendations and reforms — and, in fact, almost always does. That’s too bad: But, for good or ill, this seems to be what the people want. And not just in San Francisco.

Public Policy Institute of California survey data from 2022 shows a full two-thirds of California voters think the initiative process is a “good thing.” But, at the same time, roughly half of voters feel that the state’s ballot is too crowded.

What a predicament! This classic contradiction in voter attitudes both explains and perpetuates the status quo. To cap it off, survey data showed that a full 55 percent of California voters felt their policy decisions were superior to the governor’s or the legislature’s.

So, good luck to all the voters tackling this year’s ballot. Perhaps the means to change things is out there, somewhere. Maybe that’s what comes after Prop. BB.

Size matters to Arntz tho,

He went before the Board and said that he’d like the SF Department of Elections to Opt-Out of a State Law requiring that Big Money Funders of these Ballot Measures be listed in the Voter Handbook under the measure.

Said it used up too much paper and the Supes bought it.

You buying it ?

h.

Once upon a time, the SF Green Party would rank candidates based on their votes on critical issues at the Board. They stopped doing this in the 2010s when the Board quit voting on critical issues.

The example of Campos and then Ronen, back bench seat warmers who refuse to use the legislative pen in favor of not making waves to keep their nonprofits funded, is the best case for keeping what little direct democracy we have.

With odd year ballots eliminated, that means that remaining elections are going to get larded up with measures, many which would have gone on the odd year ballot.

Along with the right wing charter deform that marginalizes resident voices, attacks on direct democracy further excludes resident voices from the process.

I’d like to see a prohibition on candidates running for office while also putting initiative campaigns on the ballot. Something like disqualifying an elected from the ballot if they’ve sponsored a ballot measure in the previous 2 cycles.

The specter of voters weighing in on the initiative ballot checks office holders politically and that changes the way that electeds do their jobs, often for the better, knowing the elected can be publicly vetoed, with the elected humiliated.

San Francisco’s political problems are not that there are too many ways for residents to be involved in politics, either on boards or commissions or at the ballot box.

Public participation is only a political problem if one’s means are to short-circuit public opinion by foreclosing options for participation under the presumption that will further one’s self-interested ends.

“checks office holders politically”. As representative democracies show: Fear of the next election, the party, is plenty checking. Ballot measures are counterproductive in motivating capable ppl considering public service, because they encroach on elected officials’ latitude. Instead, you get more of the power tripping, self serving, narcissistic types running, which we all end up (rightfully) complaining about.

Incumbents are rarely defeated in San Francisco. There are no effective checks in that regard.

Recalls are expensive and only available to the right wing.

The progressive democratic reforms of the late 19th century, referendum, recall and initiative, are features not bugs.

“Incumbents are rarely defeated in San Francisco.”. Which actually supports my point: That’s in part because measures diminish the role of elected officials. Who go defeat themselves by rolling ballot measures themselves.

Re: Recalls. Ranked choice voting invite recall efforts: You end up with sitting duck elected officials who did not win the majority first choice vote, weak from day one.

Oh and finally, think about it, though personally I’m inconclusive: This whole mess we made ourselves with ballot measures and ranked choice voting may have contributed to this (untenable) one party state situation we’re finding ourselves these days.