Documentary filmmaker Laurie Coyle didn’t expect the calls from Mexico. She lives hundreds of miles away on the edge of the Mission District, and has been mostly working in the United States.

Nonetheless, multiple Mexican art museums clamored to screen Coyle’s 2007 documentary on the celebrated 20th Century muralist José Clemente Orozco, who spent time in San Francisco early in his career.

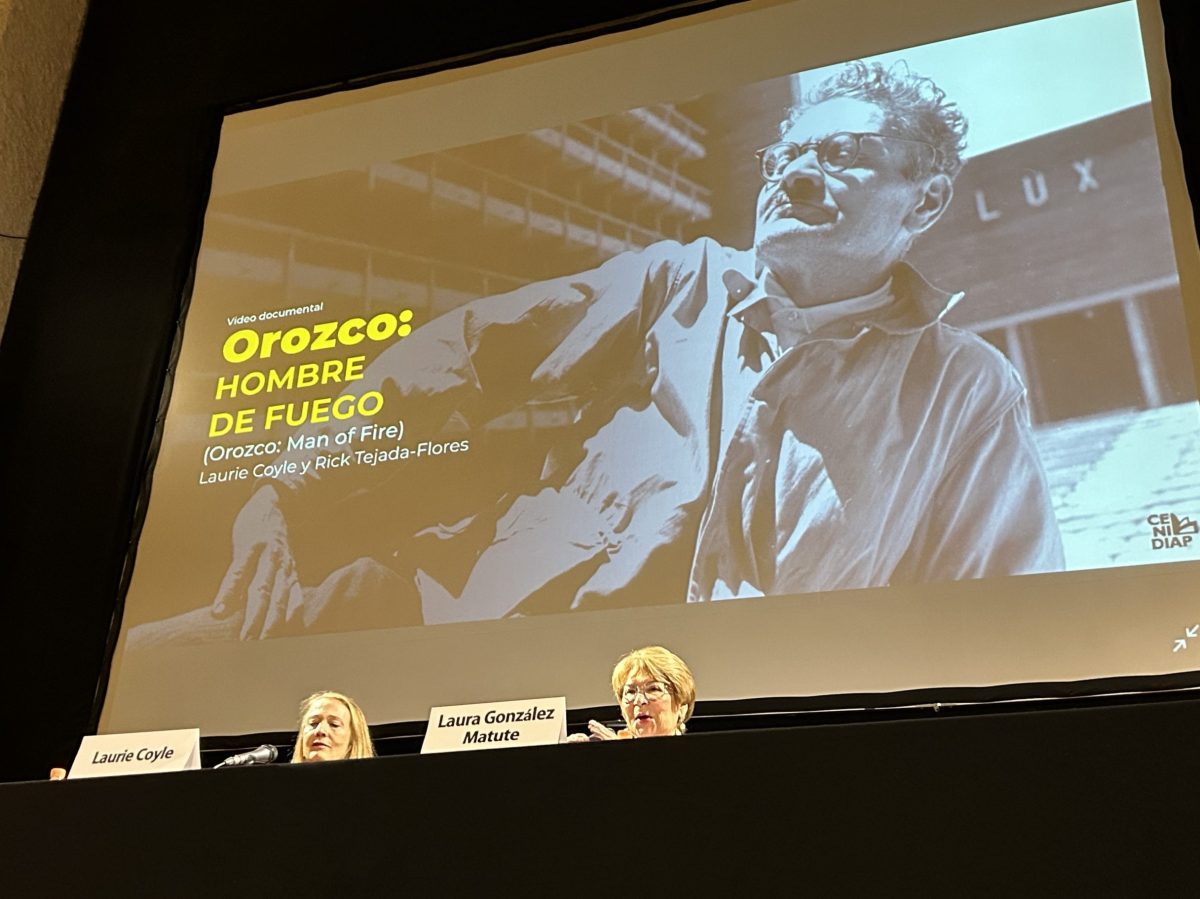

There was one small issue. The narration of “Orozco: Man of Fire” was in English — a problem for Coyle. Why should Mexicans watch a film about a renowned Mexican muralist in English?

Still, the museums were willing to show the film, even if it meant putting Spanish subtitles over the narration and English interviews. Though the artist was renowned, Coyle and co-producer Rick Tejada’s film stood out for its whimsical animations unconventional to typical artist documentaries, and museums wanted the Mexican public to see it.

“I thought it was tacky,” Coyle said, referring to the subtitles. So, some 14 years after its original run, Coyle decided to re-release her film with Spanish narration. The process took a year and involved Bay Area and Mexican contributors.

“Honestly, I had always felt a little bit guilty that we hadn’t followed up on trying to release the film in Mexico,” Coyle said. To show it in Mexico in Spanish felt like “a homecoming.”

Orozco straddled life between the United States and Mexico — first arriving in Laredo, Texas, in 1917, where U.S. customs officials examined his work, and threw away two-thirds of it — about 60 pieces. From there, he landed in San Francisco, where he spent two years enrolled in art classes, making posters for movie theaters and hanging out with local artists.

Dissatisfied with the city, Orozco moved to New York, where he eked out a living painting dolls. He returned again in 1927, where he worked with and influenced artists such as Jackson Pollock and Jacob Lawrence. His time in New York and the impact of Mexico’s Muralism movement on U.S. artists was documented in a 2020 exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York. In 1930, Pomona College commissioned Orozco for work, resulting in what’s considered the United State’s first fresco, “Prometheus.” That same summer, he finished his painting “Zapata” in San Francisco, according to the Art Institute of Chicago.

During Coyle’s research, she found other connections. She connected with a ballet dancer, Mariano Tapia, who knew the artist when he did ballet set design. Tapia lived near 21st and Mission streets. “That was so cool, that he was living in the Mission and knew Orozco,” Coyle said.

With funding from the nonprofit Latino Public Broadcasting and the Berkeley-based Lafetra Foundation, Coyle hired translator Andrea Valencia, a Mexican native and Mission District resident to do a first translation. (Valencia is a board member at Mission Local.) To match the lyricism of the English narration, Berkeley’s first poet laureate, Rafael Jesús González, and a Spanish poet in Los Angeles also worked on the script translation.

And, because the English documentary used famous Mexican actor Damián Alcázar (you may know him as Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela in the Netflix series “Narcos,” or as Alberto Reyes in the DC Comics movie “Blue Beetle”) to read Orozco’s voiceovers, Coyle wanted the same for the Spanish script. She waited nine months for a slot.

“I knew I would be disappointed if another actor did the voiceover,” Coyle explained. “He was really happy that we were going to rerelease it in Spanish.”

Spread out among the darkened rows of the National Arts Center in Mexico City (CENART) last month, dozens raptly watched the finished product unfold on screen. During a Q&A with Coyle afterward, spectators made it clear they were also pleased with “Orozco: Man of Fire’s” lyricism and how it included African-American artists’ perspectives on Orozco.

Among the audience members were Orozco’s two great-granddaughters, Gabriela and Mariana. “I want to, first, thank you so much for this work on my great-grandfather,” Gabriela told Coyle during the Q&A. “This is really masterful work.”

And then, after the screening, Coyle was offered a deal. The director of a major Mexican public television channel Canal 22 asked Coyle to sign a contract to broadcast “Man of Fire” six times over the next two years — a dream for Coyle, who had hoped to strike a similar deal for the original English version years back.

While the original goal of “Orozco: Man of Fire” was to educate U.S. audiences on the iconic muralist, Coyle said she’s thrilled the “film was embraced by the Mexican public.”

In the United States, the re-translated film also re-broadcast to fanfare on PBS, where “Orozco: Man of Fire” first premiered for “American Masters” in 2007. Coyle said PBS screening a feature-length Spanish documentary is “groundbreaking.”

Valencia agreed. “Spanish speakers are one of the biggest groups here, and the media is still very English-dominant,” she said, and the available content, in her opinion, is not varied or always high-quality.

“The fact that it’s in Spanish and read by actors you’re familiar with is amazing. You can really see that cultural content of quality is available even in the U.S.,” Valencia said.