In an unusual situation in San Francisco politics, an ethnically Chinese candidate for local office was jolted last week to see her own Chinese name being used by a non-Chinese fellow candidate.

Natalie Gee, the chief of staff for Supervisor Shamann Walton, declared her candidacy last week for the Democratic County Central Committee, the San Francisco branch of the Democratic Party. Since birth, the 38-year-old’s Chinese name has been Zyu Hoi Kan, “朱凱勤”.

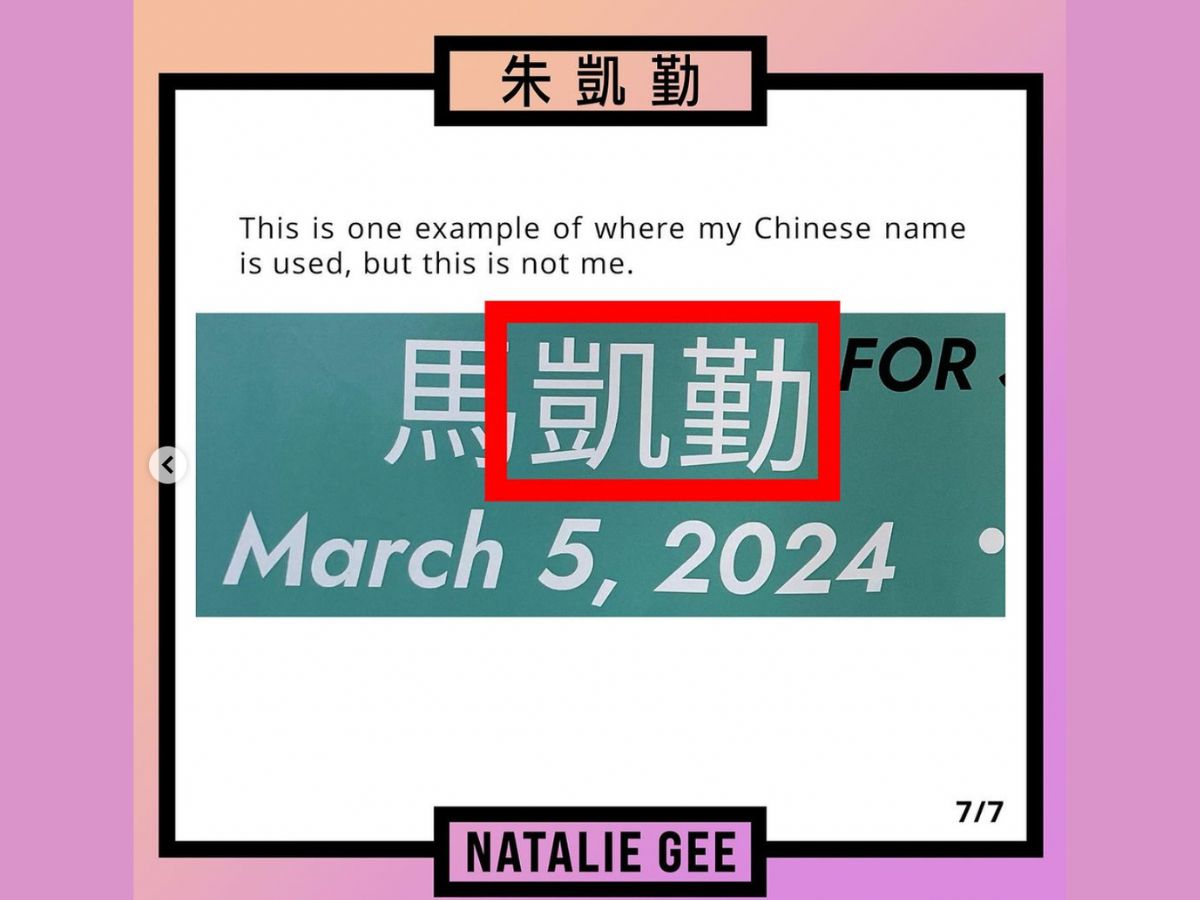

But Emma Heiken, a legislative aide for Supervisor Myrna Melgar, who is also running for DCCC, had chosen Ma Hoi Kan “馬凱勤“ as her Chinese-language ballot designation. Heiken is not ethnically Chinese, but said the name was chosen because it sounded like her English name.

Gee on Friday learned about this and, on Monday, posted on Instagram for Heiken to stop using her name, adding that the Chinese name Hoi Kan “凱勤“ is not a common name, and it carries her identity.

“People forget that, while for some people, they get to ‘choose’ the characters for a Chinese name, but for Chinese people like me, it IS my name,” Gee wrote in her post.

“No one in San Francisco has that name, and I don’t know how she got that name,” Gee said later in an interview. “It’s our pride. It’s our identity.”

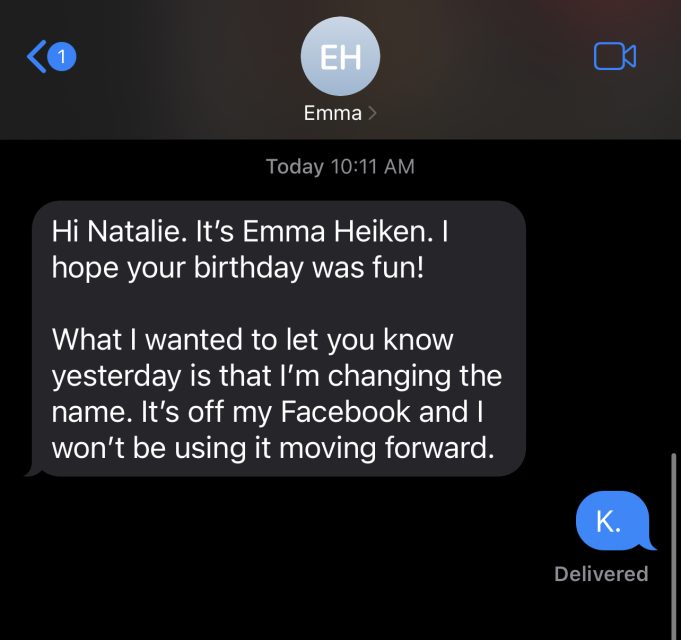

On Monday, after Gee posted online, Heiken agreed to find a different Chinese name.

“My friends and family of Chinese descent gave me this name because of the phonetic similarity to ‘Heiken,'” Heiken explained to Mission Local. “I am grateful that Natalie reached out on Friday to inform me of this issue before all the election paperwork was finalized. I called her shortly thereafter to let her know I will not be using the name.”

The situation between Gee and Heiken ended neatly, and there will be no duplicate names on the March 2024 DCCC elections. But that need not have been the case: David Ho, a longtime city political strategist, said that, in San Francisco, it is up to the general public to catch instances when candidates’ Chinese names are problematic.

Once a candidate submits a Chinese name to the San Francisco Department of Elections — at least in all published candidate guides, including for the Board of Supervisors, County Central Committees, and County Councils — there is a 10-day public review and challenge period. If the name is not challenged, altering it becomes difficult.

Leaving this matter to the public, Ho said, can too often lead to situations where a name on the ballot is far from a mere phonetic sound-alike to a candidate’s English name, but cannot be removed or changed. Ho referred to San Francisco District Attorney Brooke Jenkins’ choice to assume the Chinese name “謝安宜”. It sounds nothing like “Brooke Jenkins,” but does mean “safety and comfort.”

“It shouldn’t be us, the public, to catch every single one of the candidates running for office,” Ho said. The elections department “should hire bilingual staff to culturally assess this.”

As much as San Francisco politicians love to campaign with strategically crafted Chinese names to win the hearts of the city’s goodly number of Chinese-speaking voters, state Assemblymember Evan Low passed a bill in 2019, ostensibly regulating the use of Chinese names by non-Chinese office-seekers.

The law states that candidates who were not born with a character-based name (usually in languages like Chinese and Japanese) can only use a mere phonetic transliteration of their birth names, unless they have identified with a Chinese name publicly for more than two years.

But San Francisco’s Department of Elections has insisted that Low’s legislation doesn’t apply to the city’s local races, meaning that candidates do not need to prove the two-year usage and establishment.

Gee said her mother, Karen Gee, is an avid reader of historical Chinese literature and spent days coming up with the name Hoi Kan “凱勤”. In Chinese culture, characters in names bear meaning, usually a wish from the parents and family for the child to carry on. In Gee’s case, Hoi “凱” means victory, and Kan “勤” means diligence.

Karen Gee, it turns out, is the source of many San Francisco politicians’ Chinese-language ballot designations — including “楊馳馬” for State Assemblymember Matt Haney (meaning galloping horse), as well as “華頌善” for Supervisor Walton (meaning praising kindness).

Gee herself, who is fluent in Chinese, has also crafted Chinese names for politicians around her, including Supervisor Dean Preston, whose Chinese name, “潘正義”, means justice.

“It’s good that they want to learn about Chinese culture and want to connect with Chinese voters,” Gee said of non-Chinese candidates. “But at the same time, I think they need to be respectful of the names.”

Gee said she only learned about Heiken using her name while browsing social media. When she messaged Heiken on Instagram expressing her upset, Heiken replied “Oh, that’s funny,” and said she had no idea.

Gee pointed out that, in her email exchanges with Heiken and other city colleagues, her Chinese name has always been right next to her English name in her signature.

By Monday, Heiken and Gee agreed that Heiken would find another name.

“I had no intention or interest in going by a name already in use,” Heiken stated on Monday. “Natalie was born with this name, and it is rightly hers.” As of Monday afternoon, Heiken has stripped the Chinese name Ma Kaiqin off of her Instagram, X and Facebook accounts.

Monday happens to be Chung Yeung Festival (重陽節), a holiday in Chinese culture to honor ancestors and elderlies. It is also Gee’s Chinese lunar calendar birthday.

I find it rather unethical that non-Chinese politicians can just make up whatever they want as their name, if they are only using the character for symbolic branding purposes alone. Transliterated names should be based on the phonetics of their western name, preferably in Cantonese or otherwise Mandarin, but at least a justifiable phonetic similarity with some dialect of Chinese. The family name should come first, followed by the first name.

Hong Kong and mainland China has already standardized most western first names into Chinese already, so politicians should follow these standards by default — otherwise this is just an exercise in arbitrary branding and not based in reality.

Emma had Natalie Gee’s Chinese name on her twitter up until this article was published.

If she had planned to stop appropriating Natalie Gee’s name days ago, why did it take until today to remove it?