After a fire at 50 Golden Gate Ave. in San Francisco’s Tenderloin displaced more than 140 people on Dec. 12, landlord Mosser Companies promised to help rehouse residents, under the city’s “Good Samaritan” ordinance.

But, nearly two months later, many have not been offered stable housing from Mosser, nor received assistance from the city. They find themselves floating on friends’ couches or crammed into living rooms outside the city they called home.

“Nobody’s helping us,” said Melba Vilan, whose displaced family of four is staying in her auntie’s living room in Daly City, struggling to find an affordable place to live. “Why aren’t you guys coming to us?”

San Francisco does have a rental assistance program meant to provide up to two years of aid for those displaced from rent-controlled homes after a fire. But not everyone displaced at 50 Golden Gate qualified. The program excludes residents who have more than $30,000 in savings, no matter how low their income.

The help that Mosser promised, to assist the displaced residents find new, comparably priced apartments to the ones that are now uninhabitable, has also come up short.

Landlords are not obligated to make such an offer, but Mosser was well positioned to do so. The company remains one of San Francisco’s largest corporate landlords even after defaulting on millions of dollars in loans, and being at risk of losing hundreds of units.

“Our priority is to get you into a permanent home,” Maria Villegas, who manages several Mosser-owned properties, told the tenants at a December town hall, days after the fire.

Most residents were staying at hotels paid by Mosser for the first two weeks after the fire. The Human Services Agency then picked up the tab for three weeks, and residents expected Mosser to refer them to other buildings at their existing rent prices, as Villegas had said at the town hall.

In most cases, that failed to happen.

‘Down the path of losing everything’

Julie Trần lived at 50 Golden Gate for nearly 18 years. She responded within a couple days to Mosser’s offer of an open unit in a different building after the fire, but got a rejection. The reply from Mosser seemed intended for someone else; it was a rejection from a building she had not even mentioned to the landlord.

“Mosser had a very low number of units available. All units we have available have been assigned to residents,” wrote Villegas in an email to Trần on Dec. 24. “Please ensure you are continuing to look for temporary housing on your [own] as well.”

“I was done after that,” Trần said, who is disabled and now homeless. “You’re not even paying attention.”

She qualifies for the city-paid rent subsidy, so she decided to find her own housing.

Trần has been “couchsurfing” with friends and family in the East Bay ever since the funding from Mosser and the city for an emergency hotel room ran out. She’s looking for an apartment in a housing market with vacancies dropping below pre-pandemic levels and median rent for a 1-bedroom rising to more than $3,000.

“I’m like, oh, so this is what it’s like to be unhoused, running around with your suitcases!” Trần said.

Like others on the top floor of 50 Golden Gate, where the fire broke out, she has not been allowed back into her apartment to retrieve her belongings, so Trần’s suitcases are full of new clothes, shoes and books.

Others are caught in a double bind: They’re low-income, but have retirement savings that disqualify them from city rental aid. Joe, 66, a former resident of 50 Golden Gate, who lives on a fixed pension, is among them.

“I’m one of those people in the missing middle,” he said.

Many years back, he got a city job working as a gardener at Golden Gate Park, a role he kept for 17 years. Thinking ahead to retirement, he saved as much as he could. But suddenly, his savings “became a liability.”

After the fire, Mosser offered Joe, who lived for years in a 420-square-foot studio, a placement at his rent-controlled rate in a much smaller SRO: A room under 100 square feet, with no refrigerator. Joe offered to dip into his savings to pay the market-rate price at another Mosser building.

“I got no response from them,” he said.

Mosser’s Villegas had emailed tenants telling them to contact Veritas, another property manager, about available units at one of their buildings.

“I got crickets. Nobody returned my calls,” Joe said.

Joe was ultimately able to get into affordable housing in a building managed by the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation by scouring Craigslist.

Melba Vilan was not so lucky. Like Joe, Vilan’s family of four was refused a placement at Mosser’s McAllister Street building, where there were available studios similar to their Golden Gate apartment. Her family is now on a waitlist for affordable housing through the city.

“Within a year, we’re gonna be homeless,” Vilan said. “Do you guys want us to go down that road, down the path of losing everything?”

She’s the sole breadwinner for the family, she said, and the family of four doesn’t need much space, just a place to land.

“I’m a healthcare worker. I take care of everybody without discrimination,” Vilan said. “I’m sick and tired of not being taken care of as well.”

‘One bad day’

A situation like the one at 50 Golden Gate, said District 5 Supervisor Bilal Mahmood, is a textbook example of how a formerly stable household can slide into homelessness. “Most people become homeless,” Mahmood said, “because of one bad day that isn’t their fault.”

With the displaced residents in mind, Mahmood recently introduced a resolution seeking to raise the limit of savings you can have to qualify for displacement aid from the current amount, $30,000, to the $130,000 limit that MediCal uses.

The resolution also calls for more funding to the Human Services Agency, which he says struggled to provide adequate support to the 142 residents who were displaced in the fire.

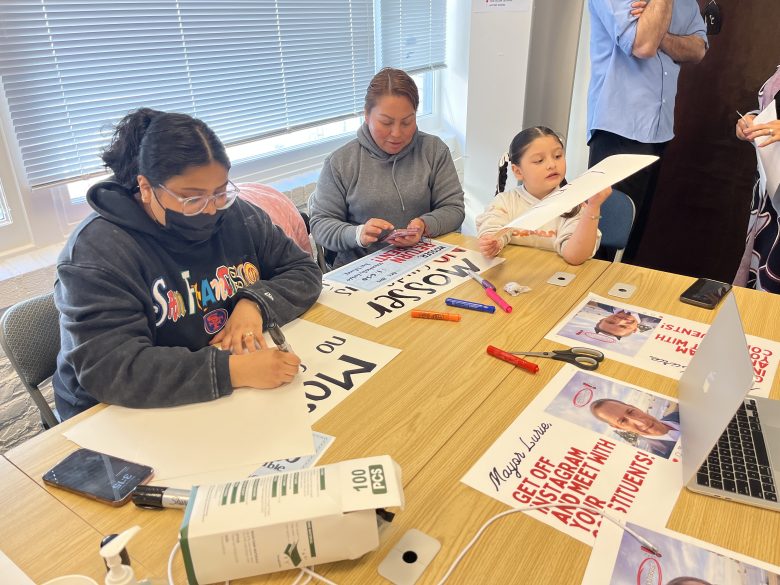

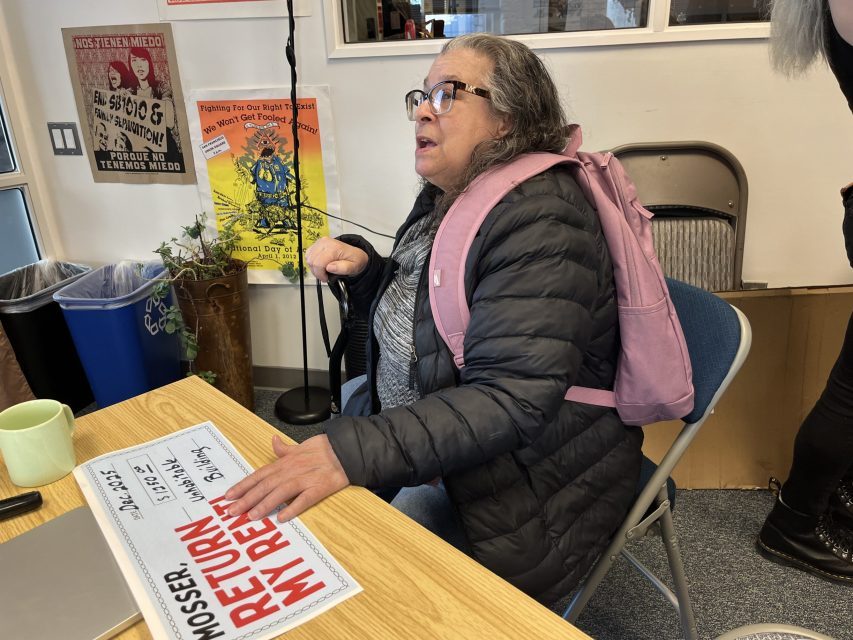

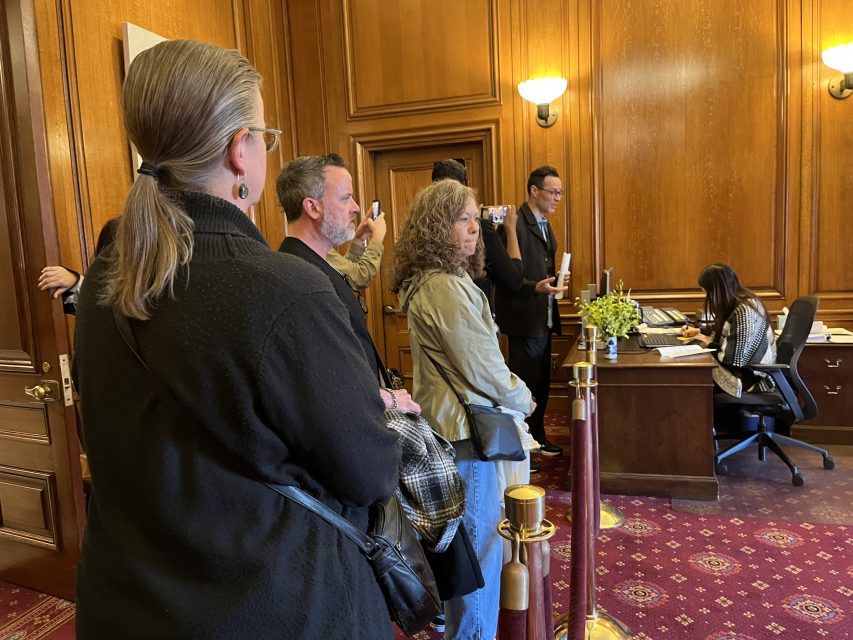

On Tuesday, as the Board of Supervisors prepared to vote on the proposal, a dozen or so former residents of 50 Golden Gate arrived at City Hall to show their support. Some held signs addressed to the mayor.

“Get off Instagram and meet with your constituents!” read one. Mayor Daniel Lurie was not in his office when the residents filed in.

The measure passed unanimously, and was sent to the mayor’s office for approval.

Asked by Mission Local on Thursday about whether Lurie would support the measure or help fund it, Chief of Health and Human Services Kunal Modi called the rental assistance process and asset limits “clunky,” and remained non-committal.

“I think the spirit we’re aligned with, of anytime we identify a way that a city program or service can work better, we’re going to try and do that,” Modi said.

In a few cases, Mosser played the “good samaritan” and rehoused some of the residents displaced from 50 Golden Gate.

Arielle Park, for example, signed a new lease with Mosser after the fire for an SRO room at their nearby building at 1499 California St. But the new place had no fridge or microwave, and the cupboards and blinds were broken.

Mosser did not respond to requests for comment about how many residents it helped rehouse after the fire.

Shortly after Park moved in, she found out that she had reached the top of a waitlist for senior affordable housing. She moved out of the Mosser building as quickly as she could.

“I’ve got one of the happier stories,” Park said. “But even a happy story isn’t very happy.”