If you live in San Francisco, then you probably know about SantaCon — the infamous annual pub crawl in which a red sea of drunken idiots in polyester Santa suits surges onto the streets, wreaking havoc amidst the holiday cheer. Perhaps you’ve even partaken in the debauchery yourself.

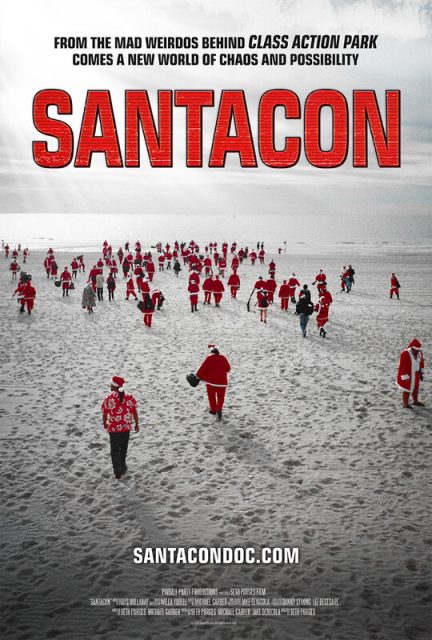

Regardless of your personal stance, SantaCon is undeniably fascinating — a spectacle that was first created here in San Francisco in 1994 by a group called the Cacophony Society. Director Seth Porges’ aptly titled documentary, “SantaCon,” details the event’s unexpectedly radical roots in anarcho-Dada theater.

Mission Local sat down with Porges to discuss how the Cacophony Society and SantaCon first came about in San Francisco, how the event has taken up a life of its own in later years and what that evolution says about our culture at large.

“SantaCon” will be screening on Feb. 5, the opening night of San Francisco IndieFest, at the Roxie Theater. You can purchase tickets here.

Mission Local: Would you say SantaCon’s inception in San Francisco was more politically motivated or a perverse desire to provoke? And how did that original impulse change once the whole thing went mainstream?

Seth Porges: When SantaCon started, the whole point was to create a blank slate, this piece of absurdism that anybody could fill with their own hopes, dreams, meaning, whatever it was. And to some people, that might have been political or an act of protest. To others, it might have just been the need and beauty to do something wonderful and fun with their friends. It might have been the hope to create a sense of shock and awe in the people around them. In the tradition of all great absurdists and surrealists, SantaCon’s origins were less about having a didactic meaning and more about creating a framework that would cause beautiful confusion in the world around, hopefully causing people to stop for a second and go, “Wait, what?”

The power of SantaCon’s early days was its novelty, its newness — that people were seeing something they had never seen before. But once you start doing that year after year after year, the novelty goes away, and all that’s left is maybe, “Hey, here’s an excuse to dress up and get drunk with my friends.”

ML: The documentary frames the beginnings of Santacon as a countercultural response to hyper-capitalism in the ‘90s. But what started as an anti-consumerist act of protest — like many born of San Francisco historically — turned into this infamous bromageddon pub crawl. What do you think that arc says about America right now?

SP: Yeah, one of the things that drew me into the story was this feeling that the life cycle of SantaCon is the same life cycle that happens to so many ideas. They begin as one thing, and they transform into another. And the thing that really drew me into the story was the fact that the creators of SantaCon had to reckon with what had happened to their creation. To me, it felt like a Frankenstein story. You have Dr. Frankenstein, who creates this thing that the world around him turns into this monster, and then what do you do? Do you run from it? You confront it? Do you ignore it?

The thing that I was so struck by while talking to people who created SantaCon was how they chose not to be angry that the world had taken their baby and turned it into something else. Rather, they said, “All right, if you’re going to do that with SantaCon, we’ll just continue to create other things that are cool.” And to me, this felt like a much bigger idea, a story worth telling because it’s about what it means to accept and live in a world you no longer understand. And how do you cope with that? Do you respond with anger? Do you respond with further creativity?

ML: I see. I know you’re a New Yorker yourself, but why do you think this started in San Francisco specifically? What were the unique cultural conditions that created SantaCon?

SP: SantaCon came from the Cacophony Society in the 1990s in San Francisco, and that’s no coincidence. This is post-hippie, pre-tech boom San Francisco when you still had the lingering embers of that creative culture. San Francisco has always been a place that creative people are drawn to. Outsiders, freaks, weirdos, people with big ideas have been drawn to places where you can kind of get away with being a little bit different. And this was before rent became this limiting factor that kept a lot of people from just doing things for the sake of doing them.

One of the big takeaways to me from the story and these people was that if Cacophony Society stood for anything, it’s that a life of exploration, fun, creativity, especially all of that with your friends, is a life worth living — it’s a noble end unto itself. And just because of the simple cost of living in places like San Francisco these days, it’s really hard to get away with just spending time and effort doing things for the sake of fun and creativity. Now, if you’re putting on a big production, people expect it to have a monetary angle, and SantaCon didn’t, and that makes it a relic of its time. In the ‘90s, again, you had all of these creative people in San Francisco, but you didn’t have the same rent pressure and the cost-of-living pressure you have today. I think because of those things, people have forgotten that you’re allowed to do things just for the sake of doing them. And I hope something people take away from the movie is the reminder that not everything has to be a hustle or gig or a job, and that if you do fun, weird, wacky things with your friends, that’s an end unto itself.

ML: Yeah, I definitely got that message towards the end where the creators are like, “You know what, just let the kids have fun!” Being a killjoy and constantly complaining about SantaCon and how it’s not as cool as it used to be is way worse than SantaCon itself. Do you think this cultural evolution we see through Santacon’s many iterations is a uniquely American phenomenon because of our hustle culture, especially here in San Francisco?

SP: I don’t think there’s anything about this that’s uniquely American. SantaCon has spread all over the world and is popular everywhere now. And it’s expensive to live anywhere in the world. I do think there’s something uniquely American about the creation of SantaCon, but not the appeal of it. This is something that began in the U.S. and then spread worldwide. I think that the unintended genius of SantaCon was how sticky, contagious and simple it was for people to get, and how many people in so many different countries instantly saw it without understanding what it was or where it came from and said, “Well, I want to do that.”

As any idea spreads, it becomes further and further from its origins and from the people who created it. And maybe in the early days, when it was just a small group of friends, it reflected the personalities of its creators. But as it becomes a Xerox of a Xerox of a Xerox, it reflects something closer to our greater cultural id, and any subtlety or nuance gets sort of ironed out in the face of the simplest interpretation of SantaCon, which is getting drunk.

ML: Yeah, it’s like Jean Baudrillard’s idea of simulation, simulacra and hyperreality. Another question I have is that in the film, there’s this notion that putting on that red suit almost activates one’s “Bad Santa” mode, like a “get out of jail free” card via anonymity. Beyond the drinking, what do you think that Santa suit does to people psychologically, especially in dense, metropolitan areas like San Francisco? Why is the debauchery so appealing?

SP: Yeah. I mean, a joke that [we] would make while making this movie was that the Santa suit was like that trope in superhero comics or movies, where somebody puts on the suit, and they instantly get superpowers. You put on a Santa suit and your personality changes. You become bigger, you become more jolly. And if you do that in the presence of hundreds or thousands of other people who look exactly like you, you also have this layer of anonymity. So people act big and boisterous. The things that keep us in check — the idea that if I act badly, somebody’s going to know and I’m gonna get in trouble — that all goes away because you’re in disguise. If you break a rule or the law, good luck to the person who’s trying to find which of the thousands of Santas did that. And the SantaCon creators, I think, stumbled onto this very early. In 1995 San Francisco, many of the wrong Santas got arrested.

ML: How do you place Cacophony Society in the broader history of American participatory mischief? You know, the stuff that later became Internet-era prank videos and such. And what did you learn about Cacophony Society’s influence that surprised you?

SP: Yeah, I kind of view Cacophony Society like this Rosetta Stone of the modern underground. I think a lot of things that are around us can be traced directly to cacophony. You know, Burning Man came from Cacophony, SantaCon came from Cacophony, “Fight Club” came from Cacophony, or just the ideas that Cacophony either pioneered or refined would become things like “Jackass” or modern Internet prank videos. I think it’s pretty amazing looking back at the things that Cacophony Society did, and just seeing its footprint everywhere around us these days.

ML: I feel like the novelty of formerly subversive acts like SantaCon, Burning Man and black tie sewer parties has faded away in this current age. Do you think there’s a modern equivalent to Cacophony, or do you think the internet and hyper visibility have changed the conditions too much?

SP: I think if you ask people like John Law (one of the original members of Cacophony), they’ll say that young people are still doing awesome things. They’re just doing it secretly. The real interesting stuff isn’t being posted on social media, and John, in particular, has sort of made it his mission to mentor and nurture young people who are interested in doing their own version of whatever it was Cacophony did in the ‘90s. And if you ask him, he’ll say that it’s still happening, but you just don’t see it because you’re not posting it on social media

I think the whole point is you have to do it yourself. Rather than looking for somebody else who has a creative idea and latching on to it, you have to sit down with your friends and come up with your own creative idea and just do it, and don’t ask for permission, you know. Just try to come up with a good idea and do it, even if it ends up being stupid or silly. At least you tried and had a good time doing so.

These guys filmed the early years of SantaCon because back then, nobody probably imagined this footage would linger for decades or be seen by anybody, so people weren’t acting in the same sort of performative manner we act today when we’re constantly being filmed by phones and surveillance cameras. So there’s this realness to the way people were acting because it was intended to be ephemeral. People weren’t doing something to be documented, shared and spread. They were doing something so they could have a good time in the moment. And I think the whole point is maybe to put down your phone and just have fun with your friends.

ML: Leaning into this idea of secrecy and, like, not documenting things, leads us kind of back to Fight Club. We don’t talk about Fight Club.

SP: No, we don’t talk about Fight Club.

ML: Seeing [“Fight Club” author] Chuck Palahniuk in the movie was super interesting, especially given how “Fight Club” and Project Mayhem [the book and film’s anti-consumerist chaos cult] are such cornerstones of our contemporary popular imagination. But “Fight Club” makes Project Mayhem seem transgressive and even cool in ways that people still romanticize. However, SantaCon, even with its anarcho Cacophony roots, often reads as the opposite: sloppy, commercial, kind of cringe. Why do you think the real-world counterpart ends up falling short in terms of swag?

SP: If anybody thinks Project Mayhem and “Fight Club” seemed cool, I think they absolutely misunderstood the book and movie. The whole point is that “Fight Club” is one of the great pieces of satire. And if people read that book or watch a movie and think it looks like a good idea, they’re 100 percent missing the point of it. And I think, perversely, if you look back at the real SantaCon or the real Cacophony, they come off to me as cool and interesting because they’re doing all these transgressive, interesting things, but they’re doing it in a productive, rather than destructive way. And I think my reading of “Fight Club” has always been that, this is what happens when angst turns into destruction, and how easy it is to take angry young men in particular and weaponize them. And if you watch it and view it as a romantic goal, I think you’re totally missing the point.

ML: Do you think those same people who are who uncritically consume media like that would see Cacophony Society in a similar way, or would those people think it’s cringe because it’s real life? Do people only want to get lost in fiction?

SP: I don’t know. I think the whole point of Cacophony Society was about creation born from destruction, but it wasn’t destruction itself. To me, the stories of SantaConand Cacophony Society are about what it means to live a good life in the rubble, what it means to look around you and see destruction, feel it and still find a way to get up in the morning, be creative and have a good life — to not be the person who’s destroying, but be the one who’s creating from the destruction. I hope that’s not cringe. There’s something so earnest about that to me. It’s really tempting to look at anything that’s earnest and react with cringe. As somebody who grew up in the irony-filled ’90s when anything that was sincere was viewed as cringe, I hope that we’ve come out on the other side and can allow ourselves to be silly, to be stupid, to be cringe without that stopping us. And I think it’s really dangerous and nihilistic to let it keep us from being creative. You have to allow yourself to be silly, you have to allow yourself to make a fool of yourself if you’re going to do anything new and interesting.

ML: Do you think that a reason why the SantaCon creators see their creation as this Frankenstein monster is because that essence of earnestness has gone away with its commercialization and mainstream-fication? If I hadn’t seen the documentary, I would have no idea that a pub crawl could have such radical roots. In the final act when they returned to their “monster,” what do you intend for the ending to do, emotionally?

SP: Well, when we shot it, I didn’t know what would happen. To me, it just felt like the natural end to the movie where these guys have to come back and face what they’ve created. Again, it’s a Frankenstein story where Dr. Frankenstein has to come face-to-face with his monster. It’s the only satisfying way for the film to end. And the thing that really surprised and struck me was, these guys — John in particular — showed up kind of as a Grinch. He was a little grouchy, a little like, “Oh my goodness. Why did I agree to do this?” But by the end of the day, he had allowed himself to not get caught up in that negativity. Instead, he was like, “Wow, actually, you know what? People are having fun. Who am I to judge that?” I hope the takeaway is that we should all be a little bit less judgmental. I went into making this movie kind of hating SantaCon, as everybody in New York does, and I walked away thinking to myself, “Why do I even care? Why would I allow myself to be upset?” People are being stupid and having fun, so let them be stupid and have fun, and hopefully that stupidity will turn into something creative at some point in the future.

ML: Yeah, I agree. I think San Francisco can learn a lesson from John and also be a bit less judgmental of young people just wanting to drink and have a good time. Last question, what is a question you wish interviewers would ask you, but never do?

SP: Oh my goodness, nothing really comes to mind. (People) generally ask pretty good questions, and I think people who’ve watched the movie understand why I was drawn to the story. As a documentary filmmaker, you spend the years it takes to make a movie and you end up on the other side a little bit changed. If it takes a couple of years, you spend so much time immersed in these worlds, you take away a little bit from the folks and learn from them. And this is a movie that was really fun to make because I got to spend time with people who I think had such a clear idea about what it means to live a good life and why we’re here in so many ways. It reminded me of the power of creativity and collaboration, and the power of just getting outside and doing fun things with your friends, and how important that is today. So, yeah, that’s my answer.