The youngest woman in the poetry class is 85. The oldest is 100. The poems are about 1,000 years old, give or take a few.

Clara Hsu, a renowned Hong Kong-born poet and executive director of the Clarion Performing Arts Center, began teaching the course in 2019 to residents of the Bethany Center, an affordable senior residential community in the Mission District that houses a sizable number of Chinese elders.

To some, the layered meanings found in these poems may seem obscure. Yet for the elders, all of whom are women, they are absorbing.

“I don’t get many chances to learn new things these days,” said one 91-year-old, by way of explanation.

Hsu teaches the class in Cantonese, the only language that her students speak. Many of them came from the Canton area of China to the United States one or two decades ago to help care for grandchildren. She has found them to be a “high-functioning” and fiercely independent group.

“They like to have their own community,” Hsu says. “Do their own stuff.”

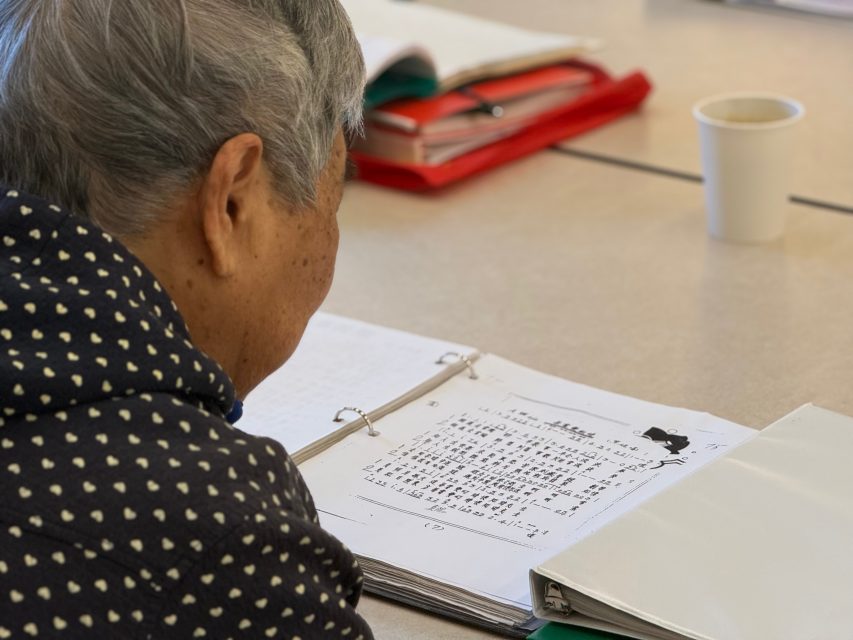

For the classes, Hsu chose a few hundred poems — usually, celebrated works from the Tang or Song dynasties — printed them out in large font, and placed them in folders provided to each student.

“In autumn, I climb up the mountain to enjoy the scenery,” Hsu said on a recent Tuesday, explaining a Tang Dynasty poem praising the beauty of autumn (山行). “Once I’m up there, I find myself captivated by the maple leaves, which resemble flowers blooming in spring.”

Across the table, her 100-year-old student held a cassette recorder under the table, quietly recording the lecture so she could listen to it again back in her apartment.

Hsu moved on to a sentence describing a bright moon among the pines (明月松間照). “Did anyone see last night’s moon?” she asked the class. “It was so bright, golden and crimson. It was the fifteenth day of the lunar month.”

“I was already asleep at that time!” exclaimed the youngest student in the class, an 86-year-old, who is also the only student who needs a reminder from Hsu to come to class.

The young student’s penetrating laughter arrives in the classroom before the rest of her, and she cuts a dashing figure when she finally appears: One hand gripping her walker, the other holding a coffee, with her eyebrows and eyeliner meticulously drawn.

Many of the poems Hsu assigns touch on loneliness, a theme that resonates deeply for her students.

“When no one comes to visit me, there’s no need to sweep this path,” said Hsu, reading from “Arrival of a Guest (客至)” by Du Fu. “But since you’ve come to see me today, I open my door to welcome you.”

The ancient poets, Hsu told the class, often withdrew into nature after realizing their ambitions could not be fulfilled in the imperial court.

Originally, said Hsu, she debated whether to share poems about death, or even loneliness, with the students. Apart from the occasional bus ride to Chinatown, the women spend much of their time in a neighborhood where they cannot communicate with many people.

Yet Hsu decided not to shy away. “It’s good to see how ancient poets deal with this. Sometimes we are overly protective,” she said. If “you’re understanding the historical context of death and dying … you feel you’re not alone.”

“All those poems from before were so beautiful,” said the 100-year-old.

“And so profound,” Hsu added.

Although some of the grannies live with their husbands at Bethany, they attend the class alone. Hsu didn’t set out to have an all-female class, she said. She tried for years to recruit male participants, to no avail.

One said, “I don’t know anything about poetry.” Hsu replied: “There’s no homework. I’m just telling you stories the whole hour.” Another excuse: “Oh … no … It’s all women.”

One notable exception was Mr. Deng (Hsu is not entirely sure of the spelling of his last name), the only man to ever attend regularly. Deng worked hard to bring in more students, and he compiled a book of songs for the class to sing before discussing poetry.

After Deng died two or three years ago, the class shrank from a dozen students to six, or fewer. Without Deng, “nobody leads them to sing” anymore. Hsu had no choice but to take on as the group’s song-leader as well.

Locally, Hsu is perhaps best known for writing the “Gai Mou Sou Rap,” which went viral on YouTube after being performed by grandmothers a couple of decades younger than those in her poetry class.

Even in San Francisco, where one in five residents is Chinese, “nobody’s interested in Chinese poetry,” she said. “I’m lucky to have them,” she said of her students.

Initially, Hsu said, she picked relatively simple poems for the class to discuss. Many ancient Chinese poems are self-explanatory and have a mere 20 characters. But her students wanted more.

At the height of the pandemic, when the classes were held over the phone (not even Zoom), Hsu ended up teaching the entire “Three-Character Classic (三字經),” a 13th century Chinese text with 1,140 characters, at the students’ request.

Later came “Orchid Pavilion Preface (蘭亭集序),” a prose essay from almost 2,000 years ago about the fleeting nature of joy and the relentless passage of time, and “Song of Everlasting Regret (長恨歌),” a longform narrative poem about an emperor and his concubine.

Despite the upheavals China has seen in the past century, this generation of elders tend to be well-educated. “I think they all went to school, at least high school,” said Hsu. “Their education probably included poetry.”

She’s found that some younger seniors — those in their 70s or early 80s — are less interested in poetry, possibly because their schooling was cut short during the Cultural Revolution.

Hsu wishes her students would speak up more in class, but they remain shy even after years together. Most interactions involve Hsu leaning close to a student’s ear to repeat a line, or telling a granny that her phone is ringing.

Still, the class has already planned to begin its next session with two songs: “What a Lovely Forsythia (好一朵迎春花)” and “Beloved Family (可愛的家庭).”

They will also spend the first day of the Lunar New Year together. It’s another Tuesday.

The free Chinese poetry workshop taught by Clara Hsu takes place every Tuesday from 10 to 11 a.m., and is open to all Cantonese speakers. The program is supported by Ruth’s Table, Front Porch and Department of Disability and Aging Services.