San Francisco’s upzoning plan has passed. On Jan. 12, 2026, the day it goes into effect, developers will be able to build taller, denser buildings on thousands of sites in the western and northern parts of the city.

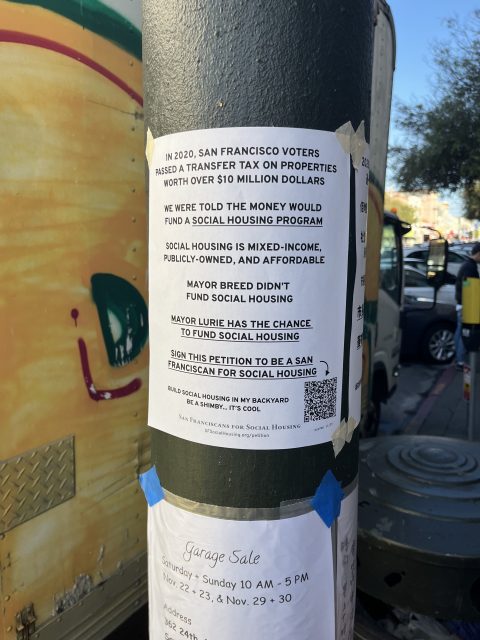

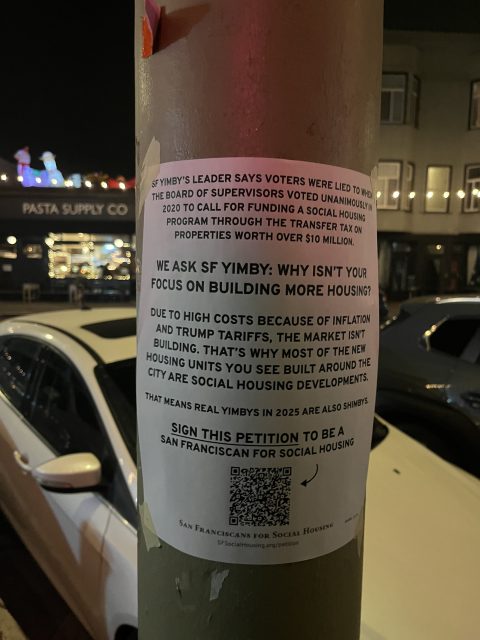

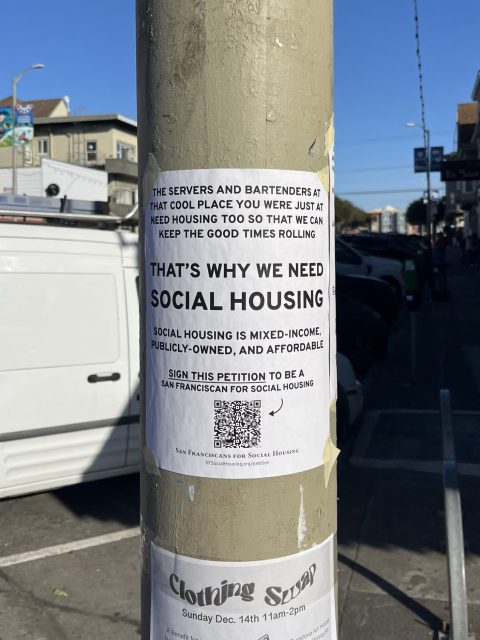

As the debate over how and where to upzone raged in City Hall, flyers taped to utility poles across the city signaled the launch of a much more DIY campaign to reignite a plan that took shape — and fell through — more than five years ago.

“Mayor Lurie has the chance to fund social housing,” the simple, black-on-white flyers read.

The posters refer to Proposition I, a ballot measure that passed in 2020 with 57 percent of the vote. Prop. I doubled the real estate transfer tax rate on buildings valued at $10 million or more. Proponents expected the new city revenue to be earmarked for new housing projects.

But the city’s mayors, who hold most of the power over the city’s budget, have so far declined to do so. Instead, the income goes to the general fund.

Enter Honest Charley Bodkin and Dylan Hirsch-Shell, the duo behind San Franciscans for Social Housing. They call themselves SHIMBYs, or “Social Housing in My Back Yard.”

An offshoot of the YIMBY movement, they think that, with enough public pressure, Lurie could be persuaded to change tack and start funding social housing in San Francisco.

Their signs urge readers to sign an online petition pushing the mayor to establish a fund for “housing that is municipally-owned (or non-profit owned), permanently affordable, and available to a wider mix of income than traditional public housing.”

Some 650 signatures have been collected so far in what appears to be a modest launch.

Hirsch-Shell is a former Tesla Motors engineer who self-funded his mayoral campaign last year to the tune of $160,000; Bodkin was his campaign manager.

“I wasn’t so much convinced that I would win, necessarily, but my interest was in promoting policy ideas that I thought were important,” Hirsch-Shell said. His platform included support for universal social housing and a universal basic income.

Bodkin was also a mayoral candidate before he met Hirsch-Shell on the campaign trail and joined his team.

Shortly after getting into local politics, he was perhaps best known for being 86ed from bars across his Haight Street neighborhood for alleged antics like inciting customers and striking a bartender in the head with a chair, according to a short documentary by Vincent Woo.

Bodkin says he’s six months sober now, and is focused on affirming local programs such as social housing and the public bank.

“I put my struggle, my efforts, not into arguing with people at bars,” Bodkin said, “but with those that actually matter, those at City Hall.”

He’s joined forces with Hirsch-Shell on the SHIMBY line, and they are plastering flyers in English, Spanish and Chinese across the city. They’re starting with Prop. I as a fund for social housing because “the will of the voters has been spoken.”

Former Supervisor Dean Preston, who authored Prop. I, is not formally allied with the SHIMBYs. Neither are the Democratic Socialists of America, arguably the most politically powerful socialist organization at the moment.

Still, Preston agrees with the SHIMBY thrust. He has been fighting for at least a portion of Prop. I funds to be spent on social housing for years.

“The transfer tax is the one opportunity you have to tax these huge real-estate speculators buying and selling mega-mansions and skyscrapers downtown to raise funds,” Preston said.

The plan, he said, was to utilize the Prop. I funds towards rent relief and social housing. The latter would be open to a variety of income levels, and owned or financed by the city, as opposed to traditional affordable housing which typically depends on subsidies and non-profit developers.

But no such funding mechanism was written into the proposition. Special taxes — taxes that go into dedicated funds — generally require a two-thirds vote, and a special tax of this nature would have been, according to the city attorney’s office, unconstitutional in California.

Instead, the Board of Supervisors passed a resolution saying the city should use Prop. I funds for affordable-housing programs, including social housing.

Because resolutions aren’t legally binding, the money went into the city’s general fund, where it has been flowing ever since. A report published in June of 2024 found that some $200 million were spent on a mix of housing related issues.

In 2024, Preston requested a report from the city that found a social housing program based on Prop. I revenue was feasible. The report indicated that cumulative revenue from the increase could total upwards of $400 million by 2026.

Although Preston, a democratic socialist, and the hundreds-strong DSA have long been vocal in the cause of social housing, San Franciscans for Social Housing is an organization of two (and “hundreds of other people that call themselves San Franciscans for social housing,” Bodkin said, referring to petition signers).

Without formal alliances, the pair may continue to address the Board of Supervisors during the minutes allotted for public comment during meetings at City Hall, or approach individual supes in public (as Bodkin has done to Mayor Lurie a couple of times before).

Even then, options are limited: Supervisors could pass another non-binding resolution asking for the money to be rerouted, but Lurie has given no indication that he would do so.

Bodkin and Hirsch-Shell are not the first to try to carve a third way through the YIMBY vs. NIMBY divide.

In 2018, the short-lived PHIMBY (“Public Housing in My Back Yard”) acronym was rolled out by the Los Angeles chapter of the DSA, which saw it as a way to mitigate the risk of gentrification posed by SB 827, a bill championed by state Sen. Scott Wiener that would have exempted most new construction near public transit from local zoning laws.

The SHIMBYs are trying to pitch a wider tent. Bodkin said he has “paid dues” to SF YIMBY and lobbied in Sacramento with Wiener and California YIMBY. More recently, he said, he also joined the San Francisco DSA.

That hasn’t stopped Jane Natoli, the organizing director for YIMBY Action, from taking to Bluesky to refute the strategy of the nascent SHIMBY movement.

“San Franciscans didn’t pass a property transfer tax that funds social housing. They passed a tax that goes to the general fund,” Natoli wrote. “You can’t just wish funds for things.”

Preston is not surprised that YIMBY leaders like Natoli aren’t lining up to rally around the cause of social housing.

YIMBYs and socialists might look like allies “on paper,” Preston said. But as far as the YIMBY organizations are concerned, he continued, “There’s a consistent pro-industry theme that is very much at odds with developing social housing in San Francisco.”

On top of all that, Prop. I may be on the chopping block next year; local and state officials are looking for ways to repeal it, or mitigate its effects.

The flyers keep going up, for now. Bodkin and Hirsch-Shell say they’re trying to build a movement. Hirsch-Shell says it’s a lesson from the campaign trail:

“Retail politics is not dead.”

Just imagine if San Francisco had actually allocated funds to social housing as Props I & K has intended, beyond what the Board of Supervisors could do in the first year. Former Mayor Breed ignored steadfast requests from Sup. Preston to make good on Prop I. There is a feasibility report from the Budget and Legislative Analyst showing the path forward. Instead we will be surpassed by Seattle and other cities moving forward on their social housing initiatives– according to the voters’ intentions.

Can someone please explain to me what exactly “social housing” is, and how exactly it’s supposed to address the shortcomings of non-profit owned affordable housing? Apparently, social housing is different because it would be owned and managed by our local government? Are the people advocating for social housing familiar with the slow moving disaster that’s unfolded over the years at Midtown Park Apartments? How about the long and troubled track record of the San Francisco Housing Authority, which at one point in its ignominious history was officially overseen by Jim Jones (yes, the same Jim Jones who led a cult and would eventually serve poisoned kool-aid to his followers). I’ll concede, conventional public housing in the US was largely sabotaged by the federal government. But in San Francisco, we’re perfectly capable of running public housing into the ground without any help from the feds.

It’s a good question. Social housing is usually defined by supporters as having four elements:

1) Some form of social ownership where it can’t be sold as a commodity on the market. In addition to government ownership, this sometimes includes community land trusts or limited equity co-ops.

2) Democratic governance by residents.

3) Guaranteed to be affordable to those who live there.

4) Universal access: it’s for everyone who needs it, though especially for those who need it most.

The key problem with SF’s current public housing is not really which level of government owns it, but that it lacks point #2, democratic governance by those that live there. As we’re aware, public housing tenants didn’t have the right to throw out corrupt SFHA administrators. #4 is another difference, since public housing in the US has become something only for the very poor (though originally it wasn’t). Having a mix of incomes could also potentially help shield social housing from political neglect, as a broader mix of people would live in it, and it could rely less (or possibly not at all) on ongoing subsidies, with relatively higher-income residents cross-subsidizing lower-income ones.

And yes, at least some social housing backers are already aware of the Midtown Park tenants’ struggle: former Supervisor Dean Preston, quoted in this article, has stood with the Midtown Park tenants since before he was elected, and in 2020 passed legislation to protect them from rent increases, as reported by 48 Hills at the time. https://48hills.org/2020/10/supes-approve-rent-control-for-midtown/

Social housing is just another term for public housing, but the fact that SF mismanages public housing doesn’t mean public housing can’t be managed competently. The city of Vienna does it well, with 2/3 of the housing owned and leased by the government.

Does Vienna have a double-decade long tradition of corrupt mayors directly beholden to the Billionaire Real Estate crowd?

I honestly don’t know that about Vienna, only SF.

It is illegal to post signs like this on public property without a permit

Please quit defacing property for selfish gain

Show so respect for property Very tacky

Please remove all postings and dont leave the tape .

Lighten up, Francis.

JE

Doing illegal things for progressive gain!!! Here we go again, the law does not apply to progressives.

Tom —

I’m sorry, are you going off on a rant because someone nailed a poster to a telephone pole? Where’s Rudy Giuliani when you need him! Call in the National Guard!

This has nothing to do with progressive or moderate or Orthogonians or Whigs. Did something heavy fall on your head?

JE

False. “The public may post information on some city-owned utility poles if the postings follow regulations outlined in Article 5.6 of the Public Works Code.” https://sfpublicworks.org/services/posting-signs

Actually it’s not enforced so you can just be mad to zero avail.

Just imagine if San Francisco had actually allocated funds to social housing as Prop I & K has intended, beyond what the Board of Supervisors could do the first year. Mayor Breed ignored steadfast requests from Sup. Preston to make good on Prop I. There is a feasibility report from the Budget and Legislative Analyst showing the path forward. Instead we will be surpassed by Seattle and other cities moving forward on their social housing initiatives– according to the voters’ intentions.

““San Franciscans didn’t pass a property transfer tax that funds social housing. They passed a tax that goes to the general fund,” Natoli wrote. “You can’t just wish funds for things.”

Natoli is absolutely correct. If Prop I had formally earmarked these funds for subsided housing then it would have required a 2/3rds vote. It only got 57%.

So this money is not for affordable housing. It is for whatever the Mayor says it is for. The proponents of Prop I tried to have it both ways – only need 50% plus 1 to pass but still have earmarked funds. It doesn’t work that way.

It’s a pretty unhelpful statement from the org whose whole thing is supposedly about getting to yes and building housing!

We all agree that the use of the revenue was not legally binding, because it couldn’t be under the California Constitution (not even with a two-thirds vote, in this case), but folks would like the mayor and supervisors to honor the intent and build social housing.

Hence the point of pressuring the Mayor to do the right thing with the money, as the article is all about? I mean let’s read it again?

So should they just spend it on whatever they want? $200,000,000 is an insane amount of money.

Build stuff. Make space for people. Make life better.

Build the stuff the people in need, need. Don’t just build anything and call it altruism.

This was a great read. More stellar reporting from what seems to be a rising star in the world of SF journalism…

The Prop I money was never intended to be lumped into the General Fund with no direction or oversight. Did $200,000,000 just disappear in the ether with no progress made towards building affordable housing at all? Who is in charge of spending all of this money anyway? If its the Mayor then he should explain to local San Franciscans why this money earmarked for housing wasn’t used for that purpose.

A general tax, no matter how it is gussied up, no matter what board resolutions gets passed, that gets on the ballot by supervisors and passes with 50%+1 of the vote goes into the general fund. The mayor, because of unitary budget authority, decides how or whether those revenues get spent.

SF progressives primary electoral wins over the past decade have been running and winning revenue measures that gift conservative mayors more and more resources with which to screw progressives.

Progressives never condition their fundraising on policy changes. They just throw more and more money at their opponents and pout when those resources are used against them.

When they keep doing this over and again, it is no longer a mistake.

“You can’t just wish funds for things.”

They’re saying pressure the politicians into doing exactly that, Derp Natoli.

Yes, they can. There’s nothing wrong with pressuring politicians, it’s our system.

YIMBYs are truly a mindless political silo. If SHIMBY or whatever isn’t the YIMBY sellout pushed by graft and developer money, I’m all for that instead.

On the off-chance that those two are reading the comments, stop solely using QR codes. I, and so many others, will never scan those. They’re too opaque and too often used to invade privacy. Print the URL underneath. Most folks have a phone that can OCR the text anyway, so it’s just as easy to navigate.

If you zoom in on the photos of the flyers, you’ll notice that we did put the URL at the bottom in plain text.

While, I’m a proponent of open spaces,I do recognize the need for housing,but instead of building new houses, S.F can do like what the property owners, of the Safeway at market and church have been planning for years, and place housing on top of existing buildings,like the Safeway at across from the Caltrain station.

I’m sorry, what is “Social Housing”?

I’m serious. Y’all are so deep in a bubble that you don’t realize that this term is opaque. Are you talking about shared apartments? Group homes? What?

Get a job Move somewhere where you can afford to live Why do others have to pay for you to live here ?

The handouts are getting old

How about helping those that contribute and pay your way ?

Why are taxpayers and homeowners requests for help in their neighborhoods never addressed !

Move to a socialist country .

Quit whining Mature a little

Life is unfair

What Preston did not learn from Mamdani is that you listen to, don’t freeze out, people who are or voted for your opponents. Unlikely alliances can be quite productive.

In this case, let these two try to call the question on whether YIMBY are going to walk their talk.

When YIMBY fail to do the work for social housing like they go to the mat for luxe condos, then YIMBY will be confirmed as manipulative liars.

Wake up you two, S.F. residents spoke when they struck down Dean Preston. That era of S.F. is dead. Preston took it too far and people got sick of it. They voted.

Next.

No thanks to a public bank. This city has 16 billion dollars, I think most residents would prefer a refund not more waste in the form of a public bank.

Slab City is clearly the perfect solution for anyone looking for “free housing.” After all, every social housing project turns out exactly the same way, and who wouldn’t want that? Much better idea: work harder—or go build your own flawless society from scratch.

Thanks Elon, but why did you commit visa fraud?

I’m against slab housing, which went out in the 80’s. But public housing that works, is at 22nd between Valencia and Mission st. it does not look like a housing project at all, plus it has an open space for children and parking underneath, then there the units on Cesare Chavez street, that replaced a soviet era high rise,and where drug dealers threw their rivals or people that didn’t pay off the 20th floor. Then mayor Willie Brown, got rid of those units and replaced it with-town house style housing, that fit into the character of S.F.

Does anyone care what that has-been Preston has to say? He isn’t relevant anymore.

I’m unclear on what “social housing” is – other than it’s property owned by government or NGOs. That doesn’t tell me much.

If this is about how to afford to live in San Francisco ….how about we end rent control and we end subsidized housing and we raise the minimum wage in San Francisco so everyone can afford to pay market rate rents?

It would create a thousand problems to be solved, people would need to be grandfathered in….but if you worked here you could afford to live here……