At Medicine for Nightmares bookstore on Saturday night, the opening of photographer Michael Papias’ exhibit documenting the Mexican American Vaquera/x/o community looked nothing like a traditional gallery opening — and that was exactly the point.

Nestled in the heart of the Mission on 24th Street, Medicine for Nightmares is a Black and Brown-owned bookstore famous for platforming a myriad of voices. Most of the roughly 50 people gathered in its gallery space on Saturday knew each other from previous events at the bookstore.

They were there for Papias, whose 30 framed photos, capturing horses and their riders, adorned every wall of the bookstore’s gallery. Smaller prints of each photograph and merchandise from the Tortilla Press, a collective of independent artists that Papias belongs to, were laid out for sale on a side platform.

A table serving fresh (and free) pan dulce and torito de cacahuate, a creamy Mexican drink made with peanuts, was set up next to the entrance.

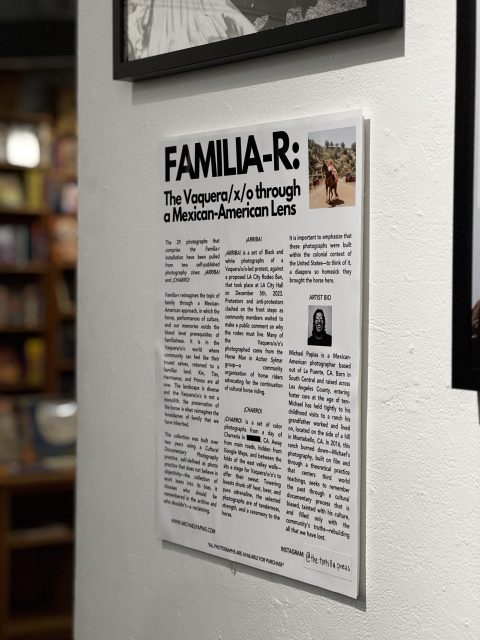

The exhibit, titled “Familia-r: The Vaquera/x/o Through a Mexican American Lens,” is a photographic tribute to the Mexican community of Vaquera/x/os, that is “loosely translated to horse rider” but means much more, according to Papias.

Many members of the Vaquera/x/o grew up riding horses in Mexico before they immigrated to the United States, and consider it a daily spiritual practice to care for their horses, said Papias.

The 27-year-old photographer was born and raised in different parts of Los Angeles County by a Mexican father and a Mexican American mother.

For the first 10 years of his life, every Sunday, his family would take him to a ranch in the middle of industrial Los Angeles that most people “don’t even realize exists.”

They would spend the day horseback riding and “re-energizing” by connecting with their culture, Papias said. Children would learn to care for horses, play with chickens, chase ranch cats and listen to elders as they swapped stories and opened up about their lives in America and Mexico.

At 10, Papias entered the foster-care system after losing both his parents. The ranch visits stopped overnight. He felt he had lost his connection to his Mexican roots.

Five years ago, he moved back to Los Angeles and discovered that many of those childhood spaces were gone, lost to gentrification, city regulations and aging community members without a next generation to pass traditions on to.

“When we were at the ranch, that was probably some of the only times that my father and grandfather would open up about their stories back in Mexico,” said Papias. “I understood the importance of having spaces where we, as a community, can be vulnerable.”

Knowing that such spaces would only continue to disappear in the coming years, he started documenting the Vaquera/x/o community with his camera, driven by both personal reconnection and cultural preservation.

Papias remembers how his childhood was influenced by negative representations of his community in mainstream media.

“When we started this project, we really just wanted to start fighting some of those racist, horrible images that have been created for us and have constrained our identity,” he said. “We’re putting forward a new image and a new idea of who we can be seen as.”

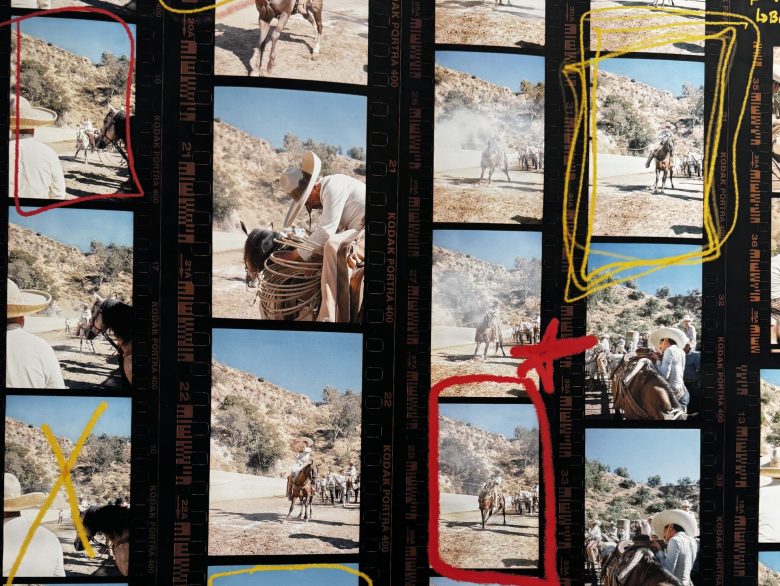

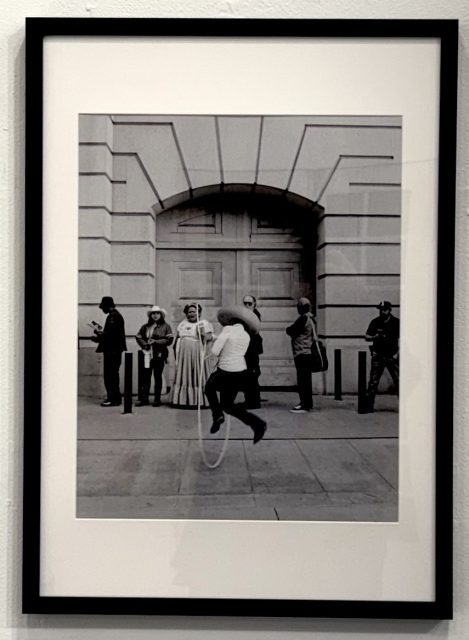

Saturday night’s exhibit had two sets of photos. “¡CHARRO!” was shot in color and “¡ARRIBA!” in black and white.

While “¡CHARRO!” shows the Vaquera/x/o during a horseback riding competition with warm colors, “¡ARRIBA!” is set against an industrial “colonized” landscape when horseback riders took over City Hall to protest a proposed rodeo ban in Los Angeles.

It’s all done on film, which Papias said helps slow his team down and remember the “invisible labor” that the Vaquera/x/o community puts into keeping Mexican traditions alive, while “also centering hand-built labor.”

Unlike a stereotypical gallery, where photographs are arranged neatly at eye level in a single row, the photographs at Medicine for Nightmares are grouped together in clusters. This was intentional, according to Papias.

“Growing up, photos weren’t something we put up in ‘gallery-style’ in our homes,” Papias said. “We put them next to each other.”

Another move away from traditional galleries: Prints could be had for as little as $3 to prevent “profiting off the community.” The term “opening night” was scrapped in favor of “pachanga,” Spanish for a gathering or celebration, to make it more welcoming, Papias said.

Even as strength and pride were on display, so too was the reality of the moment. On the exhibition description at the front of the gallery, the location where some photographs were taken was completely scratched out.

“As ICE crackdowns began, we made the choice to remove information that could be used to harass our community members,” said Papias. “This project is coming at a very important moment of policing of nonwhite people.”

“Familia-r: The Vaquera/x/o Through a Mexican American Lens” can be viewed at Medicine for Nightmares until the end of January 2026.