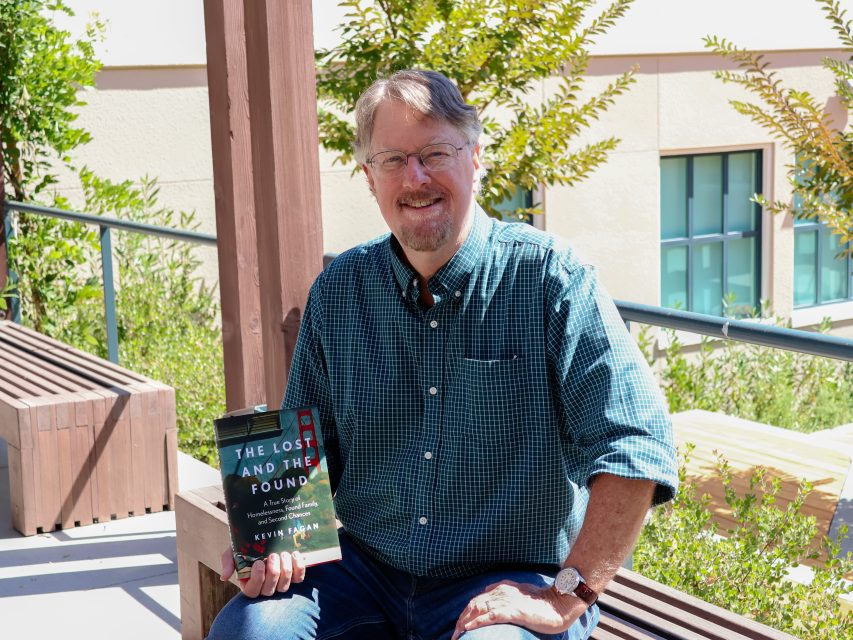

Kevin Fagan walked into Mary Collies’ 12th-grade classroom at Marin Academy in San Rafael on a recent Friday to lead a class discussion on his new book, “The Lost & the Found: A True Story of Homelessness, Found Family and Second Chances.”

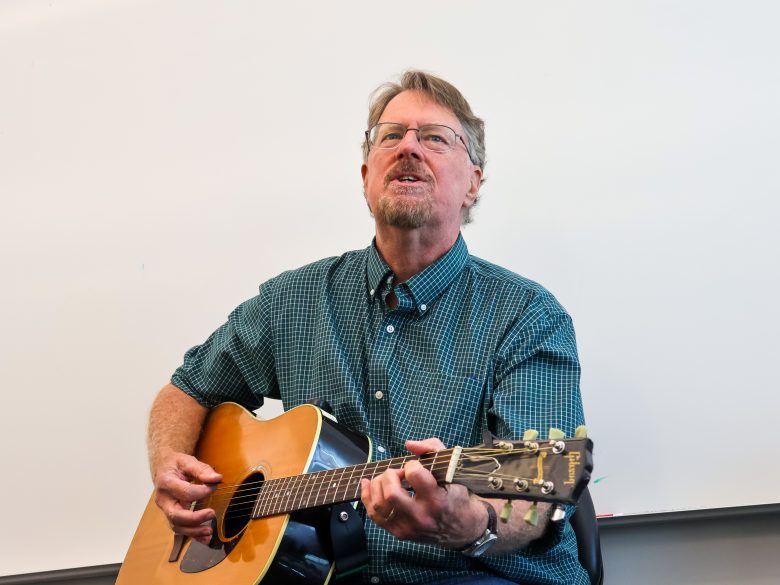

He held a guitar, its case covered in stickers like “DEMOCRACY depends on JOURNALISM,” a blending of his careers as a journalist and musician.

Fagan exchanged introductions with Collie and then launched into tales of his youth: falling in love with a Wellington, New Zealand girl, scraping by as a low-paid United Press International stringer, and busking on the side to earn $300 on good nights.

Kicked out of the house at 16, Fagan’s book draws on his personal experience of homelessness and decades of experience reporting on it for the San Francisco Chronicle.

In it, Fagan unearths his personal history and intertwines extensive research on housing and inequality with the stories of Rita and Tyson, two homeless San Franciscans he met on the streets.

Following his class discussion, Fagan joined Mission Local for a Q&A on his career and the shaping of his book. His next event is scheduled for Sunday, Sept. 14, at the Roxie Theater for The Healing WELL fundraiser, “Hope Lives Here: The Tenderloin Speaks.”

Mission Local: How did “Lost & Found” come about, and what was your writing process?

Kevin Fagan: The book grew out of journalism. In 2003, I was put out on the street by the San Francisco Chronicle managing editor, with Brant Ward, a photographer, to try to figure out why there were so many homeless people in San Francisco.

After six months of being in the street with Brant, we did a five-day series that tried to illustrate the depth of the problem, and then it moved to proposing solutions based on best practices.

The first day of the series was focusing on a colony of about a dozen addicted homeless folks on a traffic island at Van Ness in the Mission, a colony called Homeless Island. They were addicted to heroin, crack, booze; some were turning tricks to get money. All of them were panhandling in one way or another.

One of the folks in that story was Rita Grant. She was not turning tricks. But, she was addicted to heroin and did crack and had HIV. After the story ran on Rita, Rita’s sister, Pam, who was in Florida, read the story online and used that story to come out and find Rita and rescue her.

She wrote me a letter saying, “I’m coming out to get her, thanks for writing the story.”

I waited a year and went back to see how things were going with Rita and they were wonderful. She had rehabbed beautifully into the person she was meant to be. She had been an Olympics-bound gymnast, a surfer girl. They called her “homecoming queen.”

She was beautiful, smart, charming, well-liked and had just tumbled into homelessness through a series of events. You don’t just become homeless in a day, you rattle down a ladder of going through your friends, your family, crises, of course, bad choices, bad luck.

After covering a lot of homeless stories, I’ve become a homeless specialist in my career, along with other things, too, but homelessness is the closest to my heart.

I ran into Tyson Filzer when I was doing a story about a proposed shelter on the waterfront in San Francisco. Tyson was sitting on a piece of cardboard on the Embarcadero, and he gave me a really thoughtful Interview, so I put him in the paper and we ran a photo.

His brother in Ohio read this story online and called me up and said, “I haven’t seen him in seven years. I know he’s homeless. I know it’s bad. I’m raising money on a GoFundMe to get him into rehab — help me find him.”

I’ve helped a lot of people try to find their homeless loved ones, sometimes successfully, sometimes not. Tyson’s brother flew out here and we found Tyson in a day. I knew where to look, and it wasn’t very hard.

He was well-liked in the community, because he was one of those guys you could trust to watch your back. Smart, a good dude. Baron, his brother, took him back to Ohio after he detoxed and did some rehab and it was a wonderful success story.

But then, hard things happened. I don’t want to give away the ending of the book, but it doesn’t end well for Tyson. Shortly after that, I thought, “I can write a book about this.” I had pitched a book in 2016 to an agent about Homeless Island, but it got rejected because there were too many characters.

Well, this time it was just two. So, Tyson and Rita represented a couple of really important aspects of homelessness to me. Their backgrounds, how they wound up where they were, and what happened to them afterwards.

ML: How did you get your start in journalism and reporting on homelessness?

KF: I wanted to be a journalist since I was 14. My mom had been a Navy journalist and she told me it was the best job in the world. She was right. And so that was a passion of mine.

But the core driving motivators for me are that I love writing, I like having adventures, I like talking to people, and I want to do good in the world. I think journalism accomplishes all four of those, especially when you’re writing about homelessness.

ML: How did your childhood experience shape your ability to report on homelessness and connect with interviewees?

KF: In terms of empathy, I can relate to someone who’s poor. I know what it’s like to have people look at you like you’re weird. I was the kid with the broken glasses, the shitty clothes from the thrift store, pants that didn’t go all the way down to your shoes.

You get judged as a kid. Children can be pretty cruel, and so I never forgot how my background made me want to explore poverty, which then, of course, inevitably led to homelessness.

I wanted to figure out why the hell I was poor. My parents were educated and we actually had a few years where we were middle class. But then, most of the time, my father was in college and we had three kids in the family and my mom could only do part-time jobs, at the best, while watching after the kids.

It made me mad that some people have to be poor in this country. I hated not having enough food in the house, I hated having shitty clothes and I hated having to leave high school early. I never took the SATs.

Fortunately, we had really good public education in California. San Jose State was a great school, but I always wondered, could I have cut it at Harvard or Stanford? Years later, when I won the John Knight Fellowship at Stanford, I got to spend a year there and I realized, yeah, I could have done this. It helped take a little monkey off my back, but it still leaves scars on you.

ML: What was it like to build a connection with Rita and Tyson across the span of many years and then bring life to their stories?

KF: It was like doing a project story, a long project story for the Chronicle, which was where I was the longest. Only it just kept going. It was a luxury. I got to have virtually all the questions I have answered.

With Rita, I figured, all right, if I want to really show who Rita is, I need to go back to the beginning. What was it like being raised with a ton of siblings? She had a lot of brothers and sisters.

I wanted to figure out, okay, where did things turn for her, good and bad? How do you trace the arc of someone’s life when it has turned out badly or turned out well, what are the junctures?

And to do that, I had to do just the same kind of research you do as a reporter. I looked up records, looked up her yearbook and the criminal records of her as well as her various family members.

What I liked most is talking to people. I find some real happiness in interviewing people. I did probably hundreds of interviews over years between her and Tyson and all the other research I did. It was really fun to take a person’s life and jigsaw puzzle it, which is what that was like. I did that with Tyson, too.

ML: What have you learned about the best approaches needed to solve homelessness across your career?

KF: I think the root of homelessness is greed, if you had to give it one word on the most macro level. Something that I value in my perspective is having lived in New Zealand, Australia and England and traveled a lot.

One example I give is that England has a population of 60 million people and about the same homeless population as San Francisco, which is a city of about 850,000 people. They freak out about their “rough sleepers,” as they call their chronically homeless people.

The difference is that they have national health, so you don’t go bankrupt because you can’t afford a doctor. And they have living-wage laws so you can work as a janitor, punching a cash register, doing, you know, low-level paper-shuffling jobs. You can work at one of those jobs in England and be able to afford rent.

Here, you can’t work a minimum-wage job in San Francisco and afford a single-room apartment for yourself. We have the worst homeless problem of any Westernized country but we’re also the richest country on earth, which is offensive.

It shouldn’t be that way. It’s because we don’t want to share societal responsibility. Just look at the income disparity: We’re in the Gilded Age, with huge splits between rich and poor.

ML: If readers are left with one message from your book, what message should that be?

KF: Be kind, and see homeless people as human beings worthy of saving, because they need to be saved. Chronically homeless people like Rita and Tyson are not disposable human beings. They need help and they deserve help.

Kevin Fagan will appear at the Roxie Theater at 3117 16th St. on Sunday, Sept. 14 at 1 p.m. Doors open at 12:30 p.m. Tickets are $100. Funds raised benefit The Healing WELL. Tickets available here.

Fagan is right about our societal indifference to homeless people — and poor people overall — compared to the UK. We don’t see society as our responsibility.

That said, I wonder how drug addiction in the UK compares to here. It seems to be a problem for most of our homeless. Does the UK just have less availability to fentanyl and meth? Do they treat their addicts differently? I’d like to know.