In 2000, Liam O’Brien had to quit Broadway. He had been diagnosed with HIV.

“That changed everything,” O’Brien said.

The drug treatments available were impossibly expensive, even for a working actor like O’Brien, who was in the cast of Les Misérables. “A friend of mine said to me, ‘You’ve got two options: You either win the lottery, or go make yourself really poor,’” said O’Brien. “So I went and made myself really poor.”

The very day he was diagnosed, O’Brien recalled, he picked up a butterfly field guide. Quickly, his budding hobby became a full-fledged obsession.

A quarter-century later, O’Brien’s own field guide, “Butterflies of the Bay Area and (Slightly) Beyond,” will be published by Heyday Books on Sept. 30. O’Brien calls the book his life’s work.

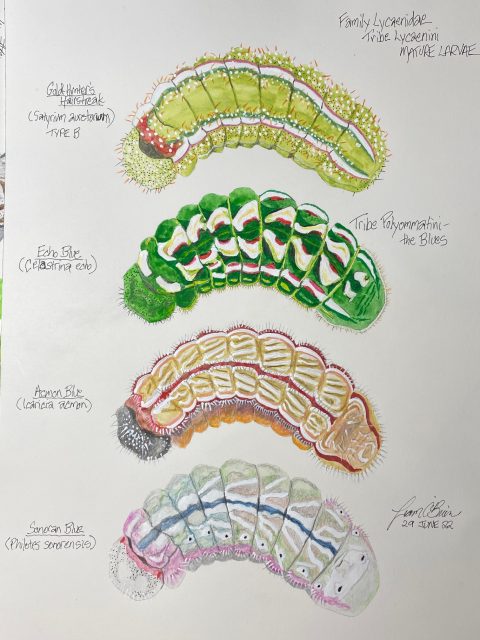

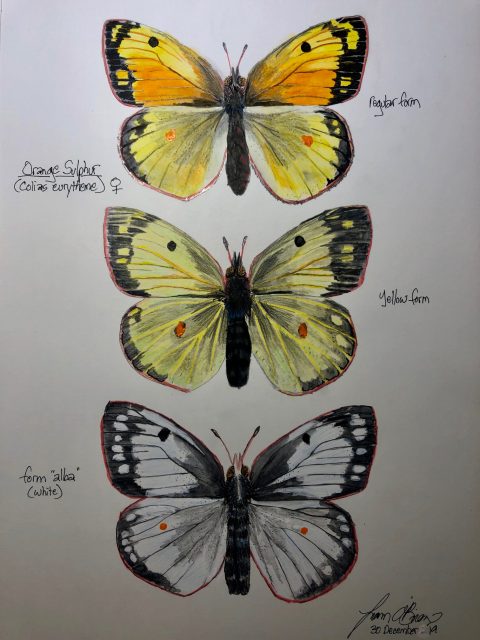

The book took him over four years; three years to hand-paint over 700 portraits of local butterflies, and another year to write and edit it.

O’Brien has a remarkably keen eye for butterflies. As we walked through Alemany Farm, a butterfly would flit briefly into view, dozens of feet away, and O’Brien identified it down to the species. He can even identify the sexes “on the wing,” or as they fly.

As his interest in butterflies grew, and he returned to live in San Francisco, O’Brien “jumped fences into vacant lots and really combed the city” for butterflies. He began to notice that butterfly populations in San Francisco had become isolated from one another. Inbreeding, O’Brien said, commonly plagues butterfly populations.

The trouble, O’Brien said, is that butterflies lay their eggs near their host plant — Green Hairstreaks congregate near Coast Buckwheat, for instance, or the Large Marble butterfly near plants in the mustard family. That limits their area.

O’Brien began working to raise awareness of this isolation and partnering with organizations like Nature in the City and The Presidio to create more continuous butterfly habitat across the city. The butterfly species that tend to struggle are the ones that depend on only a single plant to reproduce, he said, so saving them often means cobbling together pieces of land to create flyways between isolated populations, littered with their host plant.

In his book, O’Brien works to set the record straight on a few misconceptions about butterflies in general. In an intentional subversion of the field guide status quo, his drawings put the female morphology front and center.

Typically, “there’s a big, beautiful picture of the male, and then there’s a little small insert of the female to the bottom right,” O’Brien said. “I wanted to crush that patriarchal misogyny that’s been going on in field guides forever.” There’s a scientific reason for this, O’Brien added. As carriers of the next generation, female butterflies are more important.

Another misunderstanding about butterflies, O’Brien added, is that they are good pollinators. Butterflies are long and thin, and their legs hold their body away from the pollen. “They are happenstantially pollinators, but that’s not really their main thing,” said O’Brien.

So what are they good for, beyond being gorgeous? In a female butterfly’s brief 10 days of life, “she’s an egg-laying machine,” said O’Brien. And at each phase of life, the next generation of butterflies gets picked off by predators: ants, wasps, bees, lizards, birds and more.

“Butterflies really are a movable feast for everyone else,” he said. Conserving them supports a diversity of other species.

Ask O’Brien how butterflies have helped him, and the answer is a bit more nebulous. “The only answer for me is: I’m not quite sure,” he said. “I think the order calms me, in a weird way. They’re obviously beautiful. I love to paint.”

They brought him solace in one of the most terrifying times of his life. These days he loves them for simpler reasons: They interest him, and they are beautiful to witness. Simple as that.

You can pre-order O’Brien’s “Butterflies of the Bay” for $50 directly from the publisher.

To expand and connect butterfly habitats, consider supporting the Green Connections proposal, which is to great green corridors connecting parks, people, streets, animals/insects, etc https://sfplanning.org/resource/green-connections