Any given game night at Chase Center, after a Stephen Curry three, the uniform roar of the crowd can turn into a symphony of phonemes foreign to the English language.

“Jai-yo!”

“Allez!”

“Vaaaaamos perrooooo!”

In the diverse tapestry of basketball-loving Bay Area communities, the Latino demographic may be one of the most specific. Short in stature, lacking in player representation and often confined to the upper bowl, if not the esplanade altogether, Latinos have remained loyal throughout years of poor play, price inflation and moves across the Bay.

This is true even when they must cheer from afar despite being so close, like in the Mission District. In an All-Star Weekend, they are likely most represented as one of the dozens of Latinos to work three-day jobs at the activities.

No dunks

The top Latino sports bars in the neighborhood don the Warriors’ emblems and colors in their walls, but fútbol often has first dibs in the TV screens. Such was the case last Wednesday. While the Warriors played against the Mavericks, a key game for their post-season aspirations, the crowds at El Trébol at 22nd and Capp streets and El Farolito at 24th and Mission streets were glued to the Chivas win against Dominican side Cibao for the Concacaf Champions Cup.

Basketball just doesn’t come naturally to Latinos.

Before becoming a community organizer and the man behind the yearly San Francisco Carnaval, Roberto Hernández shined shoes as a child to save for the $3 ticket to see the Warriors at the Cow Palace in Daly City and the San Francisco Civic Auditorium (now the Bill Graham). He learned the game in school but, while he could free-throw like Rick Barry, the rest of his shots quickly became too easy to block.

“The school coach had to tell me I was too short to continue playing,” he recalled.

Arturo Carrillo, now the program director of the Street Violence Intervention Program, had an even harder time getting the ball to the 10-foot rim. He never fully learned the fundamentals of the game, or understood how five players fulfilled all offense and defense roles.

But they were winning. “We had Wilt Chamberlain. We had that run in the ’70s. We won in ‘75. And then they fell out for decades,” he said.

They also moved to Oakland. The TMC run and the We Believe era at the Coliseum were too small to compete with the 49ers run of Super Bowls in the ’80s and early ’90s, and the Giants’ World Series wins of the early 2010s. Everyone likes winning, sure, but Latino sports fans love baseball.

Yesenia Jiménez, a 34-year-old dental technician, grew up during those days. “Soccer always came first, but here in the Mission, we have Latinos from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Puerto Rico … ” she said. “Only after all that did it trickle down to basketball.”

It was a slow burn. When the Warriors won the Western conference title in 2015, we wrote about the lone woman celebrating on Mission Street. “No one honked back,” we wrote.

Legend has it that rookie Steph Curry made an appearance at the 2010 San Francisco Carnaval. Hernández and Carrillo swear by it. Number 30 was still so green, his team so unpopular, that there is no photographic record of his cameo.

Vacas gordas

Not only did the Warriors turn things around, but the team’s quick ascent and dynastic run spearheaded the largest of luxuries they could afford themselves: A franchise-owned, brand-new arena in the neighboring Mission Bay, inaugurated in the 2019-2020 season.

In the northeast corner stairway of Chase Center, on the corner of Warriors Way and Terry Francois Boulevard, a mural by the Mission’s own Precita Eyes collective depicts in tile-and-mirror mosaic the two longtime home cities of the Dubs: Oakland and San Francisco; the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge; the East Bay slopes and the steep streets of the city. At the center, a boy and a girl both jump for the ball.

Basketball for everyone. Warriors live for the lucky few.

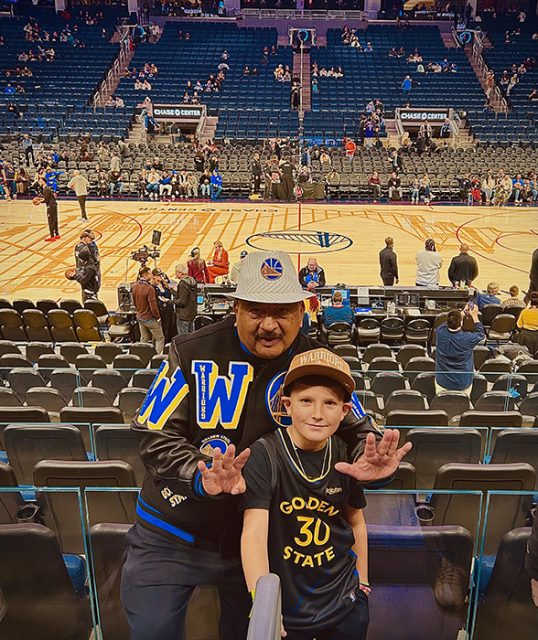

The organization has kept its ties to the Mission District through Carnaval fan booths, lowrider presence at the championship parades, and job fairs like the one that picked up dozens of Latinos to work at this All-Star Weekend activities. They have hosted groups of Latino community members at home games, and Carrillo’s own healing drum circles for hundreds of youngsters at Chase Center. They celebrate Latino Heritage Night every year. But affordability remains a big hurdle.

ceremony at Chase Center

“I buy my merch, people want to be able to represent, but it’s difficult and expensive to make it work,” said Jiménez, who attends Chase once every other month during the season. Mission locals could use a discount.

And yet, what they have taken away from the Dubs’ decade-long run seems to go beyond the emotions of in-person games. The generous game, the tightness of the squad, even the teasing and trash-talking mirror the values Latino locals tend to carry from one generation to the next.

“There is a sense of family,” said Hernández. “Through their continued presence, they have established trust, have become role models for the community, have set the bar and given us unmatched, beautiful memories.”

Hernández is particularly fond of the Currys for setting up businesses and shops that employ people on both sides of the Bay.

Jiménez appreciated the presence of la raza’s own Juan Toscano-Anderson and Gui Santos. “It’s neat to see one of our own make it,” he says, but adds that she has a soft spot for coach Steve Kerr.

“I respect a lot the way he makes a point to address serious situations happening in the world in a very respectful way.”

Carrillo, recipient of an Impact Warrior Award by the Warriors Community Foundation, declared himself prepared for whatever comes after this era.

“They did the work establishing the relationships [with the community], and that means being able to accept the transitions,” he said.

The dynasty may be on its way out, but that bond still has room to grow.

Thoroughly enjoyed this article.