Once, when Ben Bernthal was selling street poetry — he takes three words from a stranger, and turns them into a poem on the spot — a man came up and told him to write a poem about “why it matters.”

“He was almost adversarial about it,” he remembered. “He had an edge to him.”

“What are you thinking when you say those words?” Bernthal asked.

“Why shouldn’t I go home and fucking kill myself?” the man responded.

Bernthal tried to stay calm and asked more questions: “Is this a new feeling? Is it in response to something or is it something that’s been with you for a while?” The man began to loosen up and talk to Bernthal about his state of mind.

As the man wandered away to wait for his poem, though, the stakes of the situation set in for Bernthal: “I was like, ‘Okay, this is an important piece I have to write for $20.’”

Bernthal, who knew a bit about Carl Jung, decided to trust his intuition and write about the Jungian idea that a person’s suicidal ideation comes from needing part of their current life to die so that they can change and grow.

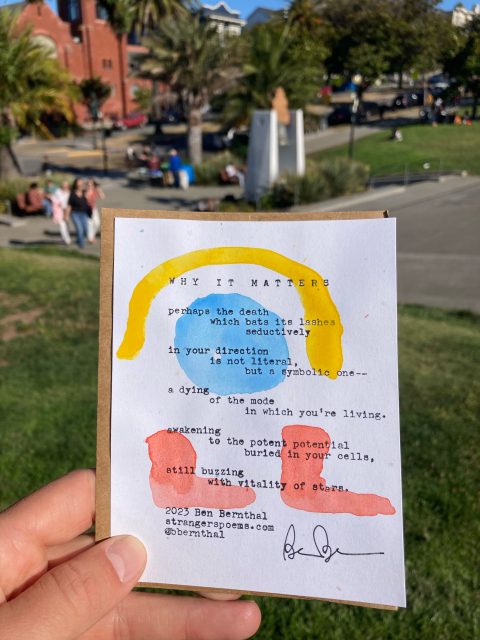

The man returned and Bernthal read out what he’d written:

“Perhaps the death

which bats its lashes

seductively

in your direction

is not literal,

but a symbolic one —

a dying

of the mode

in which you’re living.

awakening to the potent potential

buried in your cells,

still buzzing

with vitality of stars.”

The man got really quiet and said he’d need to read the poem again, but that he had a good feeling about it. Eventually, he came back with “a tear in his eye” to thank Bernthal.

It was perhaps Bernthal’s most intense experience in his poetry trade, which has become a full-time job for him: Three to five days a week, Bernthal loads a typewriter, envelopes, paper, a stool, and an ironing board into a wagon and goes to Valencia Street, Dolores Park, or another part of San Francisco to sell street poetry. Strangers walking by have the option to either give Bernthal three words and receive a custom poem, or to buy a mystery poem that Bernthal has already written and sealed in an envelope.

In exchange, Bernthal asks customers to pay $15 to $50 for a mystery poem, or $40 to $100 for a custom one.

He used to tell people to pay whatever they felt moved to give, but often wouldn’t receive enough. “I’ve had too many interactions where I spend 45 minutes with a couple and they’re gushing about how much they love their piece, and then they hand me $1,” he said.

To supplement his income, Bernthal is developing a monthly mystery poem mail subscription, and plans to start offering private sessions, where clients would meet him in a theater space in the Mission and receive several custom poems.

As he writes poems, Bernthal said that, more often than not, he’ll end up connecting with people, forming friendships and neighborhood connections.

“At this point, Valencia feels like another living room,” he said.

Some clients return often. When he used to set up at the Clement Street Farmers Market, one person visited him every week for a new poem. “She would really focus on ‘What are my three words for this week?’ and use the opportunity to self-reflect,” Bernthal said.

Bernthal thinks writing custom poems has elements of therapy, tarot, fortune telling, coaching, and portraiture. “It’s none of those things and all of them, kind of,” he said.

People often come to him hoping to understand themselves better and see how someone else perceives them. “Sometimes,” Bernthal said, “people will try to not give me words but say, ‘Just look at me and get a vibe.”

As they talk before he writes their poem, Bernthal says people often end up sharing very personal details about their lives. “I get to be trusted with people’s realest stories,” he said.

Even when someone chooses a prewritten mystery poem, Bernthal often still connects with the person.

One time, a woman bought the “why it matters” poem as a mystery poem. As Bernthal performed the poem for her on Valencia Street, a man walked past with his two “decrepit-looking” dogs. One of them brushed against the woman’s leg and then started defecating on the sidewalk.

“It totally threw off the moment,” he said.

But then, the dog owner stopped to hear Bernthal recite the poem. “His face just totally changes. He starts weeping and he’s like, ‘Do you have another one of those? I really needed to hear that tonight,’” Bernthal said.

The next day, the dog owner emailed Bernthal telling him that he’d been feeling really suicidal that night.

“This poem has a life of its own,” Bernthal said.

One of those “this is the first guy that thought of this?” stories.

This is lovely.