When I first meet Lila Travis, the director of Yggdrasil Urban Wildlife Rescue in Potrero, we bump elbows rather than shaking hands, because she’s just touched poop while cleaning out animal enclosures.

Travis then leads me from her home’s quiet residential street, where the rescue is located, into her backyard. I’m stunned. In the time it takes to walk through her front door and into the backyard, I’ve been transported into the middle of a teeming nature preserve.

The air fills with the sound of squirrels’ clacking claws as they race around on tree branches and running wheels. Turtles laze and opossums snuffle, anticipating their next meal. Stretching above them all is a leafy tree with dangling red flowers. Hummingbirds flit near the flowers, and flies buzz near the opossum poop.

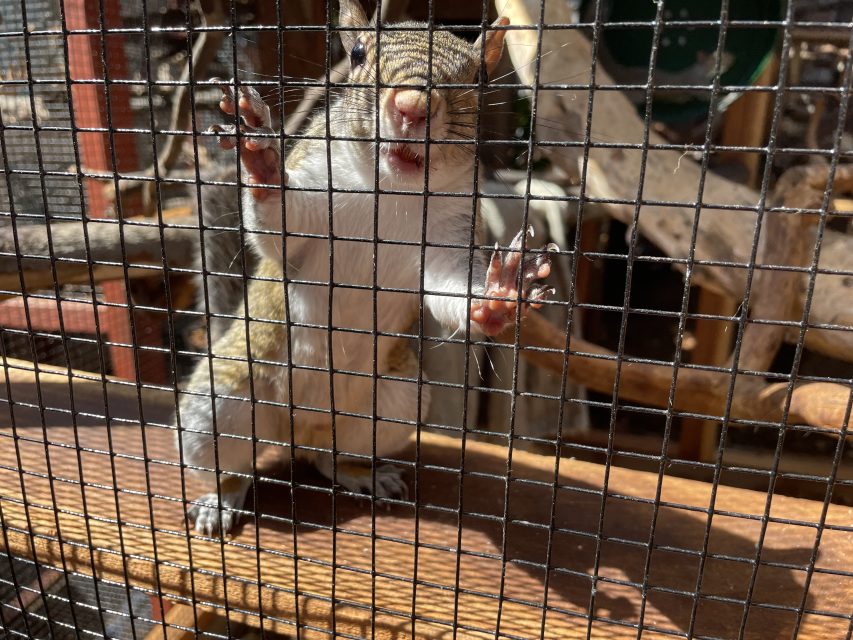

Travis takes me to the squirrel enclosures first. “All of the squirrels in this cage are combating balance issues from head trauma or being hit by a car,” she says, pointing to a cage with a couple squirrels. If you give them a few months to recover, they can regain their balance and be released back into the wild, Travis explains.

Another enclosure holds “Tailless Teddy,” an extremely fat squirrel who lost a foot and tail after he was stepped on as an infant. “Yes, he has man boobs,” Travis says.

“And then we get babies like this guy,” Travis says, pulling a baby ground squirrel out of her shirt.

“He’s too young to be able to regulate his body temperature,” Travis says. So, to keep him warm, she tucks him into her bra — a regular sports bra, just one size up to make space for him.

“I can feel when he’s awake and he’s ready for his food,” Travis says. During the day, she feeds him every two hours.

Yggdrasil — which is pronounced IGG-druh-sill and named after the World Tree in Norse mythology that contains the universe — takes in 600 to 800 orphaned and injured wild animals every year, giving them medical care and a safe place to live until they’re ready to be rereleased into the wild. Some are cared for at Yggdrasil’s main location, which is Travis’ backyard plus an infirmary and indoor space in the house next door to hers. Others are taken care of by foster families.

The squirrel in Travis’ shirt will be going to one of these foster homes later this week, where he’ll stay with eight other squirrels around his age.

“They’re gonna be so happy, running around, wrestling and playing,” Travis says, cooing to him. She gives him a little kiss on the nose and then tucks him back into her bra.

‘Why reinvent the wheel?’

Next, Travis brings me over to an enclosure containing Furla, a plump gray squirrel who had been kept as a pet.

“She has to live in a cage for the rest of her life, which is really sad,” Travis says, explaining that since her owners got her from out of state, she can’t be released back into the wild.

All too often, people try to take care of wildlife on their own, Travis says, often after stumbling across a hurt or orphaned animal. But wildlife care should be left to rescues like Yggdrasil, because it’s extremely easy to make mistakes.

Some animals raised by those who don’t know what they’re doing don’t get proper nutrition and end up disabled, she says. Others might not develop a proper fear response to humans, which can be dangerous once they’re released back to the wild.

“Why reinvent the wheel when there’s already a way to do it?” Travis asks. If someone wants to stay involved in the life of an animal, she adds, many rescues will take them on as a volunteer.

Though, to be fair, Travis got her start in wildlife rehabilitation by taking care of wild animals herself. In 1998, she came across a collapsed opossum mother that had collapsed from exhaustion after taking care of her young — opossums are marsupials and continuously nurse their joeys in their pouch, so mothers must keep up with their joeys’ appetites.

At the time, Travis didn’t know about wildlife centers, so she did “what people aren’t supposed to do” and cared for the opossum and her babies herself.

As she learned about opossum health and wildlife, Travis discovered that the nearest wildlife rescue to Oakland, where she was living at the time, was in Walnut Creek, through the tunnel. So, in 2001, she and her late husband decided to open Yggdrasil.

They built a facility in Oakland, completed a four-year training program, and passed various tests proving to the state that they were capable and knowledgeable. When Travis moved back to her hometown of San Francisco in 2011, she started taking in San Francisco animals as well.

As Travis explains Yggdrasil’s backstory, Furla darts around the enclosure, hauling some sticks up to a basket shelf.

She’s building a nest, Travis explains, an important skill for squirrels to learn before they are released back into the wild.

“I’ve never actually seen her doing this; it’s pretty awesome,” Travis says, pulling out her phone to take a video.

“I think she would have been a good wild squirrel, given enough time,” Travis sighs.

‘Heart work’

As Travis and I talk, tasks constantly pile up. Her phone, which is listed online as a “public hotline” for people with wildlife emergencies, rings four or five times over the course of a couple hours. She shows me her call log: 127 unchecked calls in the last 24 hours. Another one comes in, and it ticks up to 128.

Officers from San Francisco Animal Care and Control also drop by with a delivery: It’s a sickly raccoon with gunky eyes and oily fur that had been found inside a garbage truck.

“He’s probably been surviving off motor oil,” Travis speculates, making a plan for his care. She’ll start by injecting him with fluids to rehydrate him (she’s a certified wildlife triage nurse so she can provide basic care). Once he’s warm and feeling better, she’ll bathe him to get the oil out of his fur.

With a neverending flow of animals into the shelter, Travis ends up working 14 to 18 hours most days. But the hours are worth it: If no one was there to care for the animals, they would have to be euthanized, she explains.

“It’s my heart work,” she says. “I just hope that if I got hit by a bus tomorrow, that somebody would step up and keep it going, because it’s so needed.”

Already, some have: Roughly 100 volunteers are involved with Yggdrasil. Some foster animals at their homes — “Their backyards aren’t quite this crazy, but they’re similar,” Travis says — while others come to Travis’ backyard to help care for the animals there.

“A lot of my volunteers are people that have found orphaned and injured wildlife and brought them to me and wanted to be involved,” Travis says.

But even with everything Yggdrasil does — and on top of caring for all the animals, they also try to do monthly education events — Travis emphasizes that they are a relatively small wildlife rescue. Space limitations mean they can only take in a limited number of raccoons, and Yggdrasil doesn’t take any birds (other than hummingbirds, which die if they don’t get immediate care).

Those animals have to go to other wildlife rescues in the Bay Area — Peninsula Humane Society, Ohlone H.S. Wildlife Rehabilitation Center, WildCare, and Lindsay Wildlife Rehabilitation Hospital — Yggdrasil’s “sister organizations.”

Travis, for her part, dreams of expanding the rescue beyond her house and the homes of her volunteers by working with the city to build a “world class” wildlife center.

“That’s something that I have in our five-year plan,” Travis says. “I really want to to take it to the city of San Francisco and say, ‘Hey, help me, let’s do this.’”

As we discuss these plans, a groaning cough interrupts our conversation. Travis hurries over to an enclosure containing an opossum mother and around nine babies, some of whom are hers, some of whom are orphans she’s “providing emotional support to, because they’re really scared.”

Travis quickly diagnoses the situation: The babies are hungry and have started chewing on the mom’s ear. She grabs a plastic animal carrier and pulls the mom out of the enclosure, away from the hungry babies. She’ll have to fashion a more permanent space for the mom later, another task on her list.

“That’s the dark side of opossums,” Travis says. “There’s so many good things about them that don’t involve cannibalism.”

Thanks for this story. It’s wonderful to hear.