Public safety has become the No. 1 issue in the mayor’s race. Every major candidate has put it front and center, and the campaign is marked by attempts from contenders to outflank their rivals to win tough-on-crime votes.

But no matter the office-seeker, their actual policy proposals are similar.

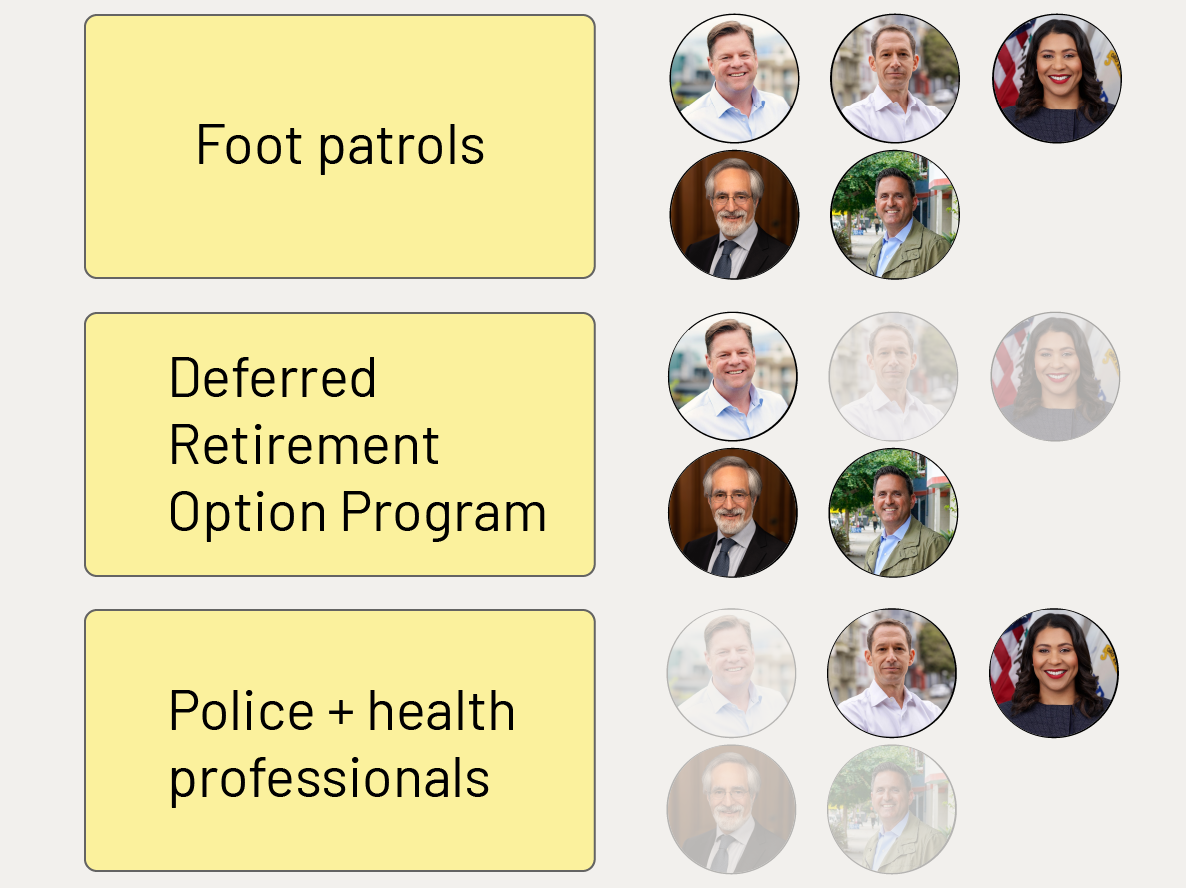

All of the five major candidates — Mark Farrell, Daniel Lurie, London Breed, Aaron Peskin and Ahsha Safaí — favor bringing foot patrols to the neighborhoods, and advocate for fully staffing the police department. Most have plans for agencies other than the police to respond to some crisis situations.

They also all support the Deferred Retirement Option Program, a November ballot measure that allows eligible police officers to simultaneously earn their pensions and salaries. This is meant to help resolve police understaffing.

So, too, is Safaí’s First Responder Loan Forgiveness Program.

To fully staff the police department, Lurie proposes incentives such as workforce housing, rent subsidies, child care and transportation support. Some of these already came with the fiscal years 2023-2026 police contract.

On staffing, Breed said she passed a $27 million budget supplemental to pay for police overtime, automated the SFPD job application process and hired back retired officers.

Where do the candidates differ?

As the incumbent, Breed points to measures she has already taken, like cracking down on drug dealing and retail theft, funding police recruitment efforts, and passing Proposition E in March, which expanded police powers and limited civilian oversight.

Peskin is the only candidate underscoring the importance of police oversight in his platform, emphasizing the need to “provide strong civilian oversight and protect civil liberties while protecting public safety.”

Others briefly mention police accountability or safeguards, and Breed, for her part, has said reform is not dead in San Francisco.

Let’s take a closer look at their proposed policies.

Mark Farrell

Daniel Lurie

London Breed

Aaron Peskin

Ahsha Safaí

Here are all the public safety policies proposed by the five leading candidates. (The proposals were pulled from the candidates’ platforms or from follow-up with each campaign, but they have been abbreviated for length.)

The candidates’ main public safety policies are very similar.

All five top candidates promise more foot patrols to deter crime.

This is nothing new: The city has for years pledged the expansion of foot patrols, which increase the community’s perception of safety, according to a 2008 city report. The actual implementation of foot patrols, however, has not always come to pass — leaving it a popular issue for politicians to call for, if not achieve. Foot patrols, notably, are not staffed when the police suffer from personnel shortages.

Back in 2017, the San Francisco Police Department moved to double the number of uniformed foot patrol officers. And in 2021, the mayor announced that more patrol officers were deployed in the city’s tourist destinations.

In 2020, District 10 Supervisor Shamann Walton and then-District 6 Supervisor Matt Haney passed legislation to create “neighborhood safety units” focusing on foot patrols. That plan stalled. In 2022, another ordinance, led by then-District 4 Supervisor Gordon Mar, was passed by the Board of Supervisors establishing a foot patrol and community policing plan. But plans rarely developed into consistent boots on the ground, proving that being in favor of foot patrols is easy while implementation is tough.

Most recently, in September 2023, Safaí, as District 11 supervisor, introduced legislation requiring the police department to further the foot and bike patrol strategy, develop a map outlining beats and submit it to the Police Commission. It will also require the police chief to submit a budget and staffing requirement for foot and bike patrols to the Police Commission each fiscal year. It passed the Board of Supervisors unanimously.

The legislation was returned unsigned by Breed, however, who cited a dearth of police officers and concerns that “producing a public document” that shows operational details will “compromise operational integrity.” The legislation passed without the mayor’s sign-off. “It’s just a matter of implementing,” said Safaí, the legislation’s sponsor. But he worried that the mayor “is not ready to embrace it.”

All candidates support the Deferred Retirement Option Program, which would allow police officers to delay retirement for up to five years, earning regular pay and pension pay at the same time. The measure is an attempt to retain officers and stanch the city’s police staffing crisis.

Peskin is the co-author of the proposal, which will be on the November ballot.

Voters approved a similar deferred retirement program in 2008, but a report from the San Francisco Controller’s Office found it costly and its effect on retention unclear. It was curtailed by the city after only three years.

A city analysis on the new proposal concluded it will cost $600,000 to $3 million in its first year and “will not be cost-neutral or generate savings.”

Nevertheless, the Board of Supervisors has advanced the measure, and it will be up to the voters to decide in November.

In terms of increasing police staffing — which every candidate wants to do — Farrell and Breed are on the same page on how to get there: Both suggest bigger academy classes, outsourcing police background checks and hiring officers from other cities.

The difference? Breed said she has already implemented all of these proposals.

“The next Academy will be the largest in years and we will add 200 more officers in the next year, and get to full police staffing in three years,” Breed promised earlier this year. The current 283rd academy class, according to the department, started with 40 students and presently stands at 33.

According to Breed’s campaign and the SFPD, this is the largest class the city has seen in five years. That is true, but this disguises a larger trend: The police academy classes have seen a decline in recent years. In 2016, for example, 48 officers graduated from the 249th class and 50 graduated from the 251st.

Farrell has also promised funding for five, instead of three, academy classes a year. Farrell says that as the interim mayor in 2018, he “averaged five new police academy classes a year with an average of over 50 recruits per class.”

But Farrell was only in office for six months from January to July in 2018. During that time, two classes graduated, one with 38 recruits and the other with 36. Farrell’s campaign subsequently said it was a typo and changed the line to refer to both his mayoralty and his time as supervisor.

Breed and Safaí both supported installing license plate cameras around San Francisco. Already, 400 such cameras are being rolled out across the city.

Lurie proposes community safety cameras, ankle monitors and geolocation technology to arrest repeat drug offenders.

Both Lurie and Breed propose teams of law enforcement and behavioral health professionals working together to help put people into treatment.

Breed talks about her record of diverting 911 calls so health professionals respond to behavioral health issues and police officers respond to crimes. That happened in June 2020 when Breed announced a series of police reforms.

Under Breed, the city launched its Street Crisis Response Team in November 2020, responding to behavioral health crises. But a city performance audit last year found a lack of coordination among teams, inconsistent goal tracking and poor contract oversight, among other issues.

Farrell, Breed and Safaí all touch on illegal vending across the city.

Farrell will make temporary illegal vending bans permanent and citywide while targeting enforcement in UN Plaza, Civic Center, the Tenderloin and along Market Street.

Breed has passed a law to do just that, issuing a vending ban on Mission Street alongside Supervisor Hillary Ronen. Months after the ban went into effect, the 16th and 24th Street BART plazas have been largely free of vendors — as long as police and Public Works staffers are present. Vending proliferates after-hours and continues along Mission Street.

In June, Breed also joined Sen. Scott Wiener to push legislation that would give police the ability to crack down on the sale of stolen goods. Repeat violators would be cited with a misdemeanor and face up to six months in county jail.

Safaí does not propose a permanent vending ban, but said he would increase penalties for fencers who “knowingly sell stolen goods.”

Lurie, Breed and Safaí all mention more collaborations between SFPD, other law enforcement agencies and community partners.

Lurie and Safaí call for more police presence in commercial areas.

Breed points to her record of expanding street ambassador programs in the Tenderloin, Downtown, the Mission and transit stations. Peskin, too, promises to add community ambassadors in every neighborhood in the city.

Here are all the public safety policies proposed by the five leading candidates. (The proposals were pulled from the candidates’ platforms or from follow-up with each campaign, but they have been abbreviated for length.)

The candidates’ main public safety policies are very similar.

All five top candidates promise more foot patrols to deter crime.

This is nothing new: The city has for years pledged the expansion of foot patrols, which increase the community’s perception of safety, according to a 2008 city report. The actual implementation of foot patrols, however, has not always come to pass — leaving it a popular issue for politicians to call for, if not achieve. Foot patrols, notably, are not staffed when the police suffer from personnel shortages.

Back in 2017, the San Francisco Police Department moved to double the number of uniformed foot patrol officers. And in 2021, the mayor announced that more patrol officers were deployed in the city’s tourist destinations.

In 2020, District 10 Supervisor Shamann Walton and then-District 6 Supervisor Matt Haney passed legislation to create “neighborhood safety units” focusing on foot patrols. That plan stalled. In 2022, another ordinance, led by then-District 4 Supervisor Gordon Mar, was passed by the Board of Supervisors establishing a foot patrol and community policing plan. But plans rarely developed into consistent boots on the ground, proving that being in favor of foot patrols is easy while implementation is tough.

Most recently, in September 2023, Safaí, as District 11 supervisor, introduced legislation requiring the police department to further the foot and bike patrol strategy, develop a map outlining beats and submit it to the Police Commission. It will also require the police chief to submit a budget and staffing requirement for foot and bike patrols to the Police Commission each fiscal year. It passed the Board of Supervisors unanimously.

The legislation was returned unsigned by Breed, however, who cited a dearth of police officers and concerns that “producing a public document” that shows operational details will “compromise operational integrity.” The legislation passed without the mayor’s sign-off. “It’s just a matter of implementing,” said Safaí, the legislation’s sponsor. But he worried that the mayor “is not ready to embrace it.”

All candidates support the Deferred Retirement Option Program, which would allow police officers to delay retirement for up to five years, earning regular pay and pension pay at the same time. The measure is an attempt to retain officers and stanch the city’s police staffing crisis.

Peskin is the co-author of the proposal, which will be on the November ballot.

Voters approved a similar deferred retirement program in 2008, but a report from the San Francisco Controller’s Office found it costly and its effect on retention unclear. It was curtailed by the city after only three years.

A city analysis on the new proposal concluded it will cost $600,000 to $3 million in its first year and “will not be cost-neutral or generate savings.”

Nevertheless, the Board of Supervisors has advanced the measure, and it will be up to the voters to decide in November.

In terms of increasing police staffing — which every candidate wants to do — Farrell and Breed are on the same page on how to get there: Both suggest bigger academy classes, outsourcing police background checks and hiring officers from other cities.

The difference? Breed said she has already implemented all of these proposals.

“The next Academy will be the largest in years and we will add 200 more officers in the next year, and get to full police staffing in three years,” Breed promised earlier this year. The current 283rd academy class, according to the department, started with 40 students and presently stands at 33.

According to Breed’s campaign and the SFPD, this is the largest class the city has seen in five years. That is true, but this disguises a larger trend: The police academy classes have seen a decline in recent years. In 2016, for example, 48 officers graduated from the 249th class and 50 graduated from the 251st.

Farrell has also promised funding for five, instead of three, academy classes a year. Farrell says that as the interim mayor in 2018, he “averaged five new police academy classes a year with an average of over 50 recruits per class.”

But Farrell was only in office for six months from January to July in 2018. During that time, two classes graduated, one with 38 recruits and the other with 36. Farrell’s campaign subsequently said it was a typo and changed the line to refer to both his mayoralty and his time as supervisor.

Breed and Safaí both supported installing license plate cameras around San Francisco. Already, 400 such cameras are being rolled out across the city.

Lurie proposes community safety cameras, ankle monitors and geolocation technology to arrest repeat drug offenders.

Both Lurie and Breed propose teams of law enforcement and behavioral health professionals working together to help put people into treatment.

Breed talks about her record of diverting 911 calls so health professionals respond to behavioral health issues and police officers respond to crimes. That happened in June 2020 when Breed announced a series of police reforms.

Under Breed, the city launched its Street Crisis Response Team in November 2020, responding to behavioral health crises. But a city performance audit last year found a lack of coordination among teams, inconsistent goal tracking and poor contract oversight, among other issues.

Farrell, Breed and Safaí all touch on illegal vending across the city.

Farrell will make temporary illegal vending bans permanent and citywide while targeting enforcement in UN Plaza, Civic Center, the Tenderloin and along Market Street.

Breed has passed a law to do just that, issuing a vending ban on Mission Street alongside Supervisor Hillary Ronen. Months after the ban went into effect, the 16th and 24th Street BART plazas have been largely free of vendors — as long as police and Public Works staffers are present. Vending proliferates after-hours and continues along Mission Street.

In June, Breed also joined Sen. Scott Wiener to push legislation that would give police the ability to crack down on the sale of stolen goods. Repeat violators would be cited with a misdemeanor and face up to six months in county jail.

Safaí does not propose a permanent vending ban, but said he would increase penalties for fencers who “knowingly sell stolen goods.”

Lurie, Breed and Safaí all mention more collaborations between SFPD, other law enforcement agencies and community partners.

Lurie and Safaí call for more police presence in commercial areas.

Breed points to her record of expanding street ambassador programs in the Tenderloin, Downtown, the Mission and transit stations. Peskin, too, promises to add community ambassadors in every neighborhood in the city.

Note: Candidates’ public safety policies are from their campaign website or follow-up with their campaigns in July 2024. Policies are summarized for brevity. You can find their full policies here or on candidates’ websites.

Major differences

San Francisco is facing a $789 million, two-year budget deficit. But none of the candidates is proposing dipping into the police budget to close that gap. In fact, SFPD’s budget grew from $714 million in fiscal 2022-23 to $776.8 million in fiscal 2023-24.

Farrell proposes closing selected public parks with “clear public safety issues” from sunset to dawn. Back in 2013, Farrell, then District 2 supervisor, supported an ordinance introduced by then-Supervisor Scott Wiener to close parks from midnight to 5 a.m.

Breed, who was also a supervisor in 2013, spoke against that ordinance and said she was “uncomfortable” with the idea that the law would only be “selectively enforced.”

Lurie also promises to integrate data systems between law enforcement agencies and various city departments, especially the Department of Public Health — systems he said are often “siloed” from one another. His proposals, he said, are meant to prompt behavioral-health treatment for those in need before they enter the criminal justice system.

After six years in office, Breed says she has always been on top of public safety, and contends that it has improved. Both violent and property crimes were lower in 2023 than before the pandemic; so far this year, crime is down about 34 percent.

Breed listed her retail-theft blitz operations, doubling drug arrests, and using bait cars and plainclothes officers to disrupt auto break-ins. All such operations expanded last year.

Breed also touts the passage of Prop. E in March, which expanded police powers and limited oversight. She also appointed District Attorney Brooke Jenkins and District 6 Supervisor Matt Dorsey before they won election in their own right.

Peskin proposes using a $230 million Walgreens settlement regarding the drug chain’s role in the opioid crisis won by the City Attorney’s Office last May to combat the fentanyl overdose scourge.

He is also the only candidate who emphasized “maintaining police oversight and civil liberties,” opposing efforts to eliminate the power of the Police Commission, proposing to ban facial-recognition technology and increase de-escalation training.

Safaí also promises to create a community safety liaison position in each police station, a satellite mayor’s office in the Tenderloin police station and anti-retail-theft positions in DA’s office and SFPD.

On top of enforcement, Safaí said he will focus on violence prevention, by prioritizing programs like at-risk youth interventions, anti-bullying and mentoring programs, job training and others.

Note: The story was updated on Aug. 23, 2024, to include Breed’s and Lurie’s support for the Deferred Retirement Option Program.

Note: Below is the same comment I made yesterday in response to piece on Farrell and “public safety.” No progress. Sigh.

Please don’t equate “public safety” with police, homeless encampments, and crime. This is the language of the sweep-’em-away conservative groups and billionaires trying to buy our elections. True public safety means being able to cross the street or wait for a bus without being crushed by a speeding car. It also means being able to afford your rent. We need to take back this term.

Great breakdown and great coverage of the candidates and their positions. This is why I always come to ML as my primary for local news (even if my politics admittedly lean more centrist by SF standards).

I do think you should ditch the long-scroll format. Otherwise, great reporting!

Thanks for this. This is a public service to the city’s voters.

None of this will change until the RICO operation of the SFPOA is broken.

The only discipline shown by SF’s paramilitary is studious adherence to blaming others: the Superior Court bench, Police Commissioners, Supervisors, 75-80% staffing levels, next up will be “my dog ate my homework.”

Foot Patrols have been the law, expanding in scope for almost two decades now. SFPOA opposed foot patrols at every step and they effectively veto the law of the city by repeatedly showing institutional contempt for it.

It is almost as if SFPOA’s failure to provide public safety increases voter anxiety over public unsafety, which gets transformed into more funding for SFPD to continue to not do their jobs to get more funding.

Politicians and judges and commissioners and chiefs come and go. The SFPOA is the constant in this political equation.

I really appreciated the rundown of the candidates stances and your putting them in historical context but the formatting of the article (scroll, scroll, scroll… a line of text appears… scroll scroll scroll) was distracting and annoying.