In the video, a medium-sized black dog cowers in the corner of an elevator. As the doors close, his owner, sporting a large sombrero that fills a third of the frame, swings his arm towards the dog. The video is shaky and blurry, but the dog’s whimper and yelp come through crystal-clear.

Is this video enough to charge the man with animal cruelty? That’s what the building manager asks Carlos Ortega, an animal control officer who has come by on a recent Monday to investigate the alleged cruelty. People in the building have heard the dog crying in the apartment, the building manager tells him.

“She’s definitely terrified of him,” Ortega responds. But he points out that, with the giant sombrero partially obscuring the view and the low quality phone video — it was the security guard’s phone recording of surveillance footage — you only see the man’s arm swing, not any contact with the dog.

Ortega asks the building manager to send him direct clips of the security footage. Maybe then it will be sharp enough to see if he strikes the dog.

“Then when we go back, we have everything,” Ortega explains. “There’s no way for him to be like, ‘Oh no, I didn’t do that.’”

Investigating this case is part of Ortega’s job as an officer for San Francisco Animal Care and Control. Every day, Ortega hops into a white van and drives around the city to address any animal-related situations that arise: Emergencies, possible cruelty and neglect, educational outreach and more. He is, essentially, an animal police officer, responding to calls from the public about animals in trouble.

Though “animal” is in his job title, as Ortega sees it, the job is just as much about knowing how to deal with people. Handling this cruelty case, for example, requires little to no specialized knowledge about animals; anyone who’s spent time around dogs can tell that this one is scared of her owner.

What it really requires is people skills: Figuring out who can send over evidence, and then staging an effective intervention with the owner.

“A majority of this job is talking to people,” Ortega explained.

Over the course of eight and a half hours that Monday, Ortega drove down Great Highway in the west, up Highway 280 and Embarcadero in the east, and ventured as far north as Fisherman’s Wharf and as far south as the Excelsior. His many stops included checking on a hurt feral cat, searching for a missing dog, talking to a woman about veterinary care for her cat, and retrieving a cat from an apartment whose owner had died.

But days are often much more eventful, Ortega said. One time, a spaniel got trapped under the boulders at Ocean Beach. With the incoming tide as his deadline, Ortega worked quickly to move a boulder and get the dog out.

“I love this job,” Ortega said. “I love helping the animals, all the rescues. I mean, my daughter’s super proud of me all the time, so that always makes things worth it.”

‘I just want to make sure your dog is safe’

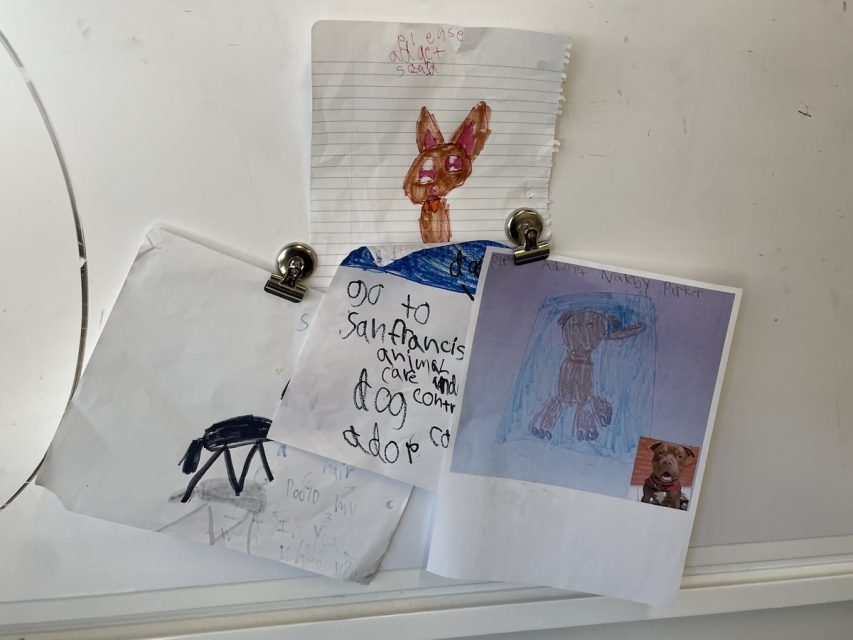

Ortega’s day started at the Animal Care and Control shelter in Potrero Hill. Dog toys and books about animals were scattered around the office, and hung on the whiteboard were advertisements for adoptable dogs drawn by Ortega’s eight-year-old daughter, including one for a pit bull named Warby Parker.

Reggie roamed the office. The tiny Yorkshire terrier puppy had arrived at Animal Care and Control in a bag, shivering, his back legs defective.

“He’s our guard dog,” an officer joked.

Ortega’s first assignment of the day was to check in on an owner who was previously investigated for keeping his dogs on a balcony without a doghouse, a legal requirement.

“It seemed like he was complying with everything that I was asking him to do,” Ortega said, adding that the owner had even had the dogs fixed at Ortega’s recommendation. But a new call said one of the dogs was outside again.

Ortega jumped into his van and headed out, getting more details from the dispatcher as he drove. The dog is tied to a door outside and is often covered in feces, the caller had reported.

But at the Balboa apartment complex where the dog and owner live — a sterile gray and white gentrification chic building with small balconies set into its side – the owner was out on a first-floor balcony with the dog, a German Shepherd with a fluffy coat. She lay calmly next to him, no feces in sight.

The owner recognized Ortega and quickly explained: She’s only outside right now because they’re cleaning the house, as the dogs had covered the apartment in fur. The dog did indeed seem to be shedding a lot; there were little balls of fluff on her coat, as if she were creating her own dust bunnies.

“Oh, man. You need to brush her out, dude,” Ortega said, suggesting that the owner take her to Pet Food Express, where he could use a velocity dryer to blow all the loose fur out of her coat. That’s what he used to do with dogs that shed when he worked as groomer for 10 years.

You can keep the dogs outside, Ortega told him, but if you do, you’ll need a bowl of water and some kind of roofed shelter they can retreat into for protection from the sun and wind.

“Just remember — and I have to do this — if she’s out here without shelter, there is a possibility that we can come back and we can seize her. I don’t want to do that,” Ortega said.

Back in the van, Ortega explained that Animal Care and Control tries to avoid seizing people’s pets whenever possible. Often, owners don’t even know they’re breaking the law and just need a warning.

The need to educate owners is a common refrain for Ortega. As he sees it, there’s much that people should learn about animals. For instance, many people chase after stray dogs, but when dogs are chased, they run — often into traffic. Calmly approaching them is better.

Many San Franciscans also don’t know how important it is to leash their dogs, which is a pet peeve of Ortega’s. Leashing decreases the risk of dogs biting others, or being bitten by something larger, like a coyote.

Not everyone, however, appreciates his advice. Once, Ortega advised a woman walking her “tiny, snack-sized dog” in Golden Gate Park to use a leash, because coyotes were around. She yelled at him, so he walked away.

“I just want to make sure your dog is safe,” he told the woman. “That’s it.”

‘More good people than there are bad’

The next call of the day took Ortega to Monterey Heights to pick up a tan German Shepherd-Akita mix from a couple. The dog is their daughter’s, the father explained, but they haven’t been able to get in contact with her, and can’t manage the dog.

Puma, who is referred to by a pseudonym, stood calmly in the driveway, his armpit shaved and a little bloody. A pit bull had bitten him, and the vet had put him on antibiotics and painkillers.

Animal Care and Control was taking Puma in as a stray, so the daughter would have four days to retrieve her dog, or he would become property of the shelter and potentially get adopted out.

But his daughter shouldn’t get the dog back, her father said. She didn’t care for it well, he said, and her place was a mess, and not ideal for a pet.

And though Puma has bitten people, “the dog is nice,” the father explained. “It’s just the people who are bad.”

Ortega agreed, and said that Animal Care and Control could do a “property check” before allowing the daughter to reclaim Puma.

Puma didn’t go gently, however. He strained to get away, but Ortega scooped him into the van.

He probably recognized the van and didn’t want to go, Ortega said. Puma had already been at the shelter several times in the past few months; he’s one of the Animal Care and Control’s “frequent flier” pets.

Next on the agenda was a visit to another frequent flier dog, Ohana, also a pseudonym. Her owner likes to spend time with her by the In-N-Out at Fisherman’s Wharf. Ortega tries to check on them at least once a month, always toting a bag of food big enough to last two or three days.

“He’s a really sweet guy,” Ortega said of the owner, who is homeless. “Doesn’t do the right thing all the time, as far as protecting his dog.”

One time, a woman asked to hug Ohana, Ortega said. The owner said yes, but Ohana didn’t like it, and nipped the woman in the face. She then reported the bite to animal control.

Ohana is often very friendly to people at first, but then “she’s like, ‘I’m done,’ and she’ll nip at you,” Ortega explained. (“Don’t hug dogs you don’t know,” Ortega advised).

But first, a different dog bite report took priority.

Then more calls came in. Towards the end of the day, Ortega got a call about a sick bird walking around near Oracle Park, the place where Ortega met his wife, who was working in the dugout at the time. (“I cried when they won the World Series,” he said).

As he drove past the stadium, Ortega spotted the seagull sitting in a corner of Willie Mays Plaza. The bird’s appearance — gray with scraggly feathers — probably made people think it was sick, Ortega said, but he actually looks like that because he’s a fledgling.

Walking is also normal behavior, not a sign of illness, Ortega added. “He’s tired from learning how to fly, which is why he walked all this way,” Ortega said.

Ortega used the towel and protective gloves to quickly scoop up the bird, who bit Ortega’s gloved finger in protest.

“It’s good he bit,” Ortega said, explaining that it means the bird is alert, and has appropriate fear of humans.

Ortega placed the bird under some bushes with long spiky leaves, where he could rest without getting bothered until he was ready to try flying again.

He’d like it if the people who’d called about the bird were still there, Ortega said, so that he could teach them about gulls.

But still, it’s heartening, he said, that people want to help.

“This job’s taught me that there’s more good people than there are bad,” Ortega said. Like with the cruelty case today; people were helping, which is the case more often than not.

Ortega reflected on the dog in the elevator. “That dog was showing body language that is consistent with a dog that gets hit all the time,” he said. “He’s basically trying to defuse any kind of anger or threat that the owner is giving him by showing soft, non-threatening behavior and just constantly flinching.”

Seeing that upsets Ortega, but mostly it motivates him to go out and find good evidence.

“I just get motivated to find out what the truth is,” Ortega said. “I just want to make sure these people get what they got coming.”

ahhh these officers are heroes – helping those who cannot speak for themselves. thank you officer ortega! you and all your comrades should get massive raises <3

I met Officer Ortega and another officer when a raccoon got trapped in my attic. They were very kind and much more courageous than I was. SF Animal Care and Control is a completely wonderful organization.

I call animal control few times to pick up an injured cats or stray dogs in Treasure Island and He arrives fast! Thank you Carlos !

We need more people like him!

Thank you, Officer Ortega, for your kindness and professionalism. No wonder your daughter is proud!

Thank you for writing about Animal Care & Control! I’ve been super curious what it’s like to work there ever since my family turned in a dog that was running around the intersection of Cesar Chavez and Folsom at rush hour. This was a nice glimpse into their work.