When San Francisco medical examiners arrived in mid-July to deal with a tenant who had died alone in his Pacific Heights apartment, they noticed a brown tabby cat, hidden underneath the sofa bed’s mattress, watching them carefully.

They called Animal Control Officer Carlos Ortega, who soon arrived with a cardboard crate and large net pole, ready to retrieve the cat.

Ortega searched around the musty two-room unit, the light of his flashlight glinting off the framed black-and-white pictures of ’40s and ’50s movie actresses that covered the walls. Before long, Ortega found the tabby hiding behind an upholstered chair.

As the cat emerged from behind the chair, Ortega reached out calmly and quickly for the scruff of his neck. The cat hissed and stretched his legs out in protest, but it was too late. Ortega lowered him into the cardboard crate, and took him to the Animal Care and Control’s facility in Potrero Hill.

For pets in “extraordinary circumstances,” like this cat, Animal Care and Control steps in to care for them, acting much like a social welfare agency, but for animals instead of children.

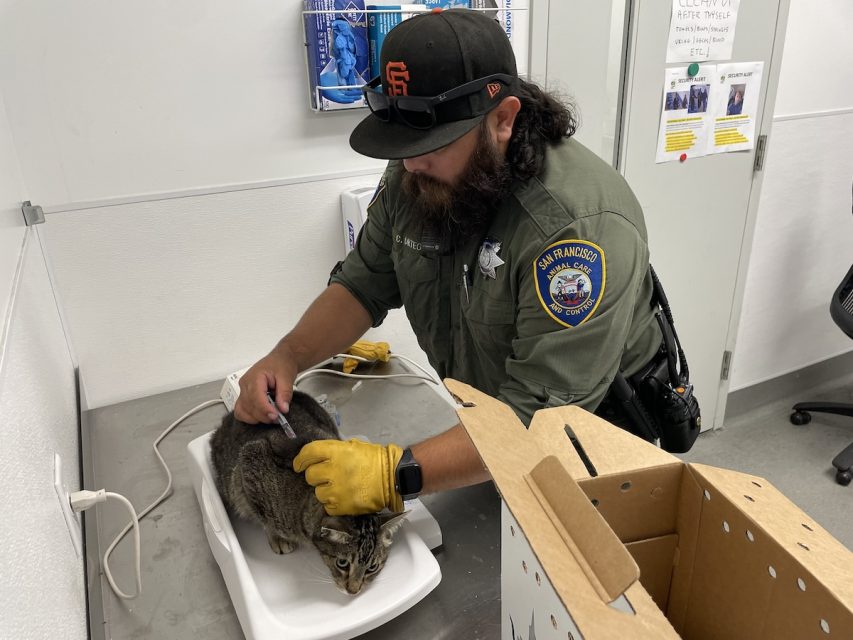

At the city-run shelter, the cat put up little protest as Ortega vaccinated him and scanned his microchip, discovering that he was 14 years old and named Thumper. He was now in custody. Other animals end up in custody when their owners are arrested, hospitalized, or face other difficulties.

Once pets are in custody, Animal Care and Control will reach out to family, friends and, if available, the owners, to try and find someone to retrieve the pet. If no one has come for the pet, after two weeks they become the property of Animal Care and Control and potentially eligible for adoption.

Though the city-run service only promises to hold custody animals for 14 days, if an owner needs more time and has been communicative with the shelter, they will try to hold the animal for longer. The longest they’ve ever held an animal for is three months, according to ACC operations manager Ariana Luchsinger.

Animal Care and Control’s over-capacity, however, has made such extended stays unlikely.

“If we’ve got a shelter full of custody cases that we’re constantly extending, there’s no room for strays. There’s no room for animals whose owner is under investigation for cruelty or neglect,” Luchsinger said, adding that the 14 days allotted is already significantly longer than the four-day hold for strays.

But even if Animal Care and Control had space for more than the 55 to 70 dogs it can accommodate at one time, it’s better for them to leave as soon as possible, Luchsinger said, because the shelter environment can be stressful. New people come in and out, the food is different, and their owner is nowhere to be seen. In some rooms, dogs bark almost constantly, so Animal Care and Control staff try to keep the scared, shy dogs in a separate room.

Fetch, ‘treat hockey,’ and more

To help the 10 to 20 dogs that are in the custody program at any given time, a team of volunteers comes to the shelter every day to walk, play, and provide the animals with much-needed socialization.

One of those volunteers, Pauline Le, has worked with the custody dogs for the past eight years. Each shift, she consults the list of custody dogs currently at the shelter, checking the notes that the staff or other volunteers have left. One dog might love hot dogs but not cheese, and be too nervous to be taken outside. In that case, Le might plan to play “treat hockey” with that dog, throwing treats around the enclosure for the dog to chase.

For the dogs that are ready to leave their kennels, Le will take them to the turf-covered play area built at the center of the shelter. Because the custody dogs aren’t owned by Animal Care and Control, they don’t take them out of the shelter to walk.

Dogs and volunteers have their quirks. Le loves to play fetch and hide-and-seek with the dogs, crouching down somewhere in the yard and covering her eyes until the dog finds her. Le recalled one dog’s attachment to a large unicorn. “He would rip up his bed if there was any stuffing in there, but he would not touch the unicorn,” she said.

Workers particularly bond with the handful of “frequent flier” dogs that have been through Animal Care and Control four or five times, generally because their owners often need the help.

“Sometimes we get to know them so well that we have some volunteers that will be like, ‘Okay, I’m stopping by McDonald’s today to pick up chicken nuggets for him,’” Le said.

Before too long, though, most owners come for their pets. “People want their dog back, like, 99.9 times out of 100,” Luchsinger said.

But even after they leave the shelter, the connection remains. Le recalls running into one of the “frequent flier” dogs, Maggie, with her owner on Market Street. Maggie, who Le describes as “really sweet,” had been through the custody program multiple times and was owned by an unhoused person.

Thumper’s custody journey is just beginning. Right now, all he knows is that the body of the owner that had cared for him was taken out of his home by strangers, that a man had then put him in a little box, and that he now lives in a two-level kennel with a litter box, a nest, and a paper tray filled with food. He seemed to take to it immediately. When he arrived, Thumper leaned forward, looked around, sniffed, and then leapt in.

The sweet senior cat Thumper mentioned in this article is now available for adoption at SFACC