Imagine a planet inhabited by a people who don’t differentiate one song from another. In this culture, when someone starts singing or reciting a tale about a local character, friend, rival or mythic figure, celebrating, mocking or teasing them, all the verses draw on shared themes and phrases, as if the music was one big song, a bottomless well from which everyone draws.

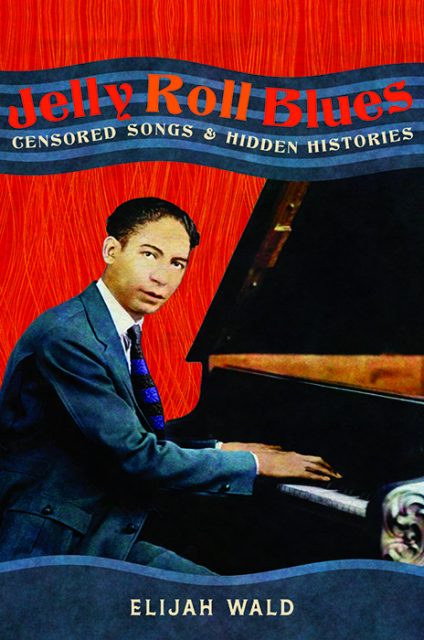

This isn’t a world conjured by Ursula K. LeGuin. Rather, it’s a slice of New Orleans circa 1903, as described by prolific music journalist, guitarist and cultural historian Elijah Wald in his new book “Jelly Roll Blues: Censored Songs & Hidden Histories.” Using the recordings of seminal jazz pianist and composer Jelly Roll Morton that Alan Lomax made for the Library of Congress in 1938 as his road map, Wald uncovers a lost continent of working-class culture long suppressed by musicologists and historians as too ribald, earthy and obscene for public dissemination. Rarely has L.P. Hartley’s oft-quoted line seemed so apt: “The past is a foreign country: They do things differently there.”

Wald, whose previous work has examined The Dozens, Mexican narrative ballads about drug traffickers, and Dylan’s epochal performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, will talk about the songs and culture he uncovered Saturday April 13, at Bird and Beckett Books & Records in Glen Park, and Monday, April 15, at Pegasus Books Downtown in Berkeley. A veteran musician himself, the Philadelphia-based writer will be demonstrating some of the material covered in “Jelly Roll Blues,” which raises the question of just how explicit he’ll be rendering the material.

“I ask people what they’re comfortable with,” Wald said in a recent phone conversation, noting that Morton and the other Black performers covered in the book often tailored lyrics according to their audience. “I don’t have to say ‘fuck’ a lot. I have a PG version. For these two Bay Area events, I don’t think I’ll have gear to show images or play recorded music. But I’ll have my guitar and I’ll gauge the audience, which is what Jelly Roll Morton did.”

Born and raised in New Orleans — the most commonly cited year is 1890 — Morton died in Los Angeles in 1941. He’s remembered today as an exemplary pianist and the first major jazz composer and arranger. He made a series of popular records with his Red Hot Peppers in mid-1920s Chicago and New York and, while his compositions “King Porter Stomp,” “Black Bottom Stomp” and “Wolverine Blues” became jazz standards, he was widely seen as passé by the time he connected with Lomax. (The Broadway production “Jelly’s Last Jam” draws so lightly on Morton’s life and career, it’s an exaggeration to say it was loosely based on him.)

Lomax wasn’t interested in Morton’s foundational contributions to jazz, a style he considered slick and commercial. He was interested in Morton’s memories of the music and characters he encountered in the District as a teenage pianist working in brothels and after-hours joints. The white clients usually wanted to hear sentimental pop tunes of the day, but the Black and Creole working women were partial to slow blues, an emerging idiom that had yet to be codified or named. Rather than distinct songs, the proto-blues often consisted of widely circulating refrains, verses and themes (though Morton was famous for generating extemporaneous lyrics).

On the Library of Congress sessions, “Lomax labeled most of Morton’s blues performances generically: ‘New Orleans Blues,’ ‘Honky Tonk Blues,’ ‘Low Down Blues,’ and it is a matter of choice whether we consider them separate songs or examples of a single, infinitely variable framework,” Wald writes.

Many of the most enthralling threads that Wald follows in “Jelly Roll Blues” involve chasing down the origins of words, phrases, and songs that Morton recorded for posterity, including a good deal of material that wasn’t released for decades because it was deemed too explicit (indeed, publishing it or sending it through the mail would have been a federal crime until the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark mid-1960s obscenity rulings).

Lyrics from songs like “Hesitation Blues,” “Stavin Chain,” “Uncle Bud” and “Alabama Bound” serve as bread crumbs that led Wald to the suppressed recordings, oral histories and court records that captured the parlance of the sporting life, that confluence of sex workers, gamblers, fancy men and musicians who lived in and around urban red-light districts and rural work camps. Morton’s sobriquet Jelly Roll itself was a term for female genitalia, and the songs Lomax coaxed out of the often-reluctant pianist conjure a world that was rapidly receding, even in 1938.

“In terms of this material, the huge forgetting was Prohibition,” Wald said. “The cliché is that everything got wilder during Prohibition, but it’s simply not true. They wanted to keep quiet.”

Sporting women were often patrons of the musicians, and the musicians responded by playing the music the women wanted to hear, “which helps explain why there were a lot of songs about lesbianism and cunnilingus,” Wald said. “We’re so used to thinking that dirty folklore was for the boys. But these songs about sex work weren’t so much sexy as they were about work.”

“Jelly Roll Blues” is likely to serve as a launching pad for dozens of doctoral dissertations. Wald did a lot of the research online during the first years of the pandemic, cultural spelunking made possible by the vast archives of newspapers and turn of the century publications that have been digitized. But there are still hundreds of archives only available on-site, and entire swaths of history unexplored, like gay life in New Orleans at the turn of the 19th century.

“There are books on gay Chicago and New York, but nothing on New Orleans, which was a gay center,” said Wald, who experienced hundreds of jaw-dropping moments uncovering lyrics and interviews suggesting how widely explicit material was performed.

“A huge part of this is that I hope other people read and think, ‘I wish he’d explored this more fully.’ It’s a big arrow for other people, pointing them, ‘Hey, there a lot of paths waiting to be explored!’ There are a lot of rocks to be turned over, a whole world of blues that nobody has looked at.”

Jelly Roll had a club called Jupiter on Columbus and Pacific for a couple of years (approx 1919-1923). vol two ‘Our Roots Run Deep: The Black Experience In California, 1900-1950.’ eds. Agin Shaheed & John William Templeton

Attended the event at B & B, and bought the book! It’s meticulously researched and full of surprises. Thank you so much: I never would have known about this if you hadn’t published this article!

I watched the livestream on Bird & Beckett’s YouTube Channel. Will post the link in my wesite link.

This is great! I love seeing Andrew’s byline on Mission Local.

One small correction, the author’s event at Bird & Beckett is on Saturday April 13th from 6:00 to 7:30pm.