On Wednesday around midday, two old friends gathered for lunch at a home on Shotwell Street. It had been more than two years since they last saw each other, and nearly 14 since they first met in Mexico City, but they hugged, kissed and chatted like no time at all had slipped by.

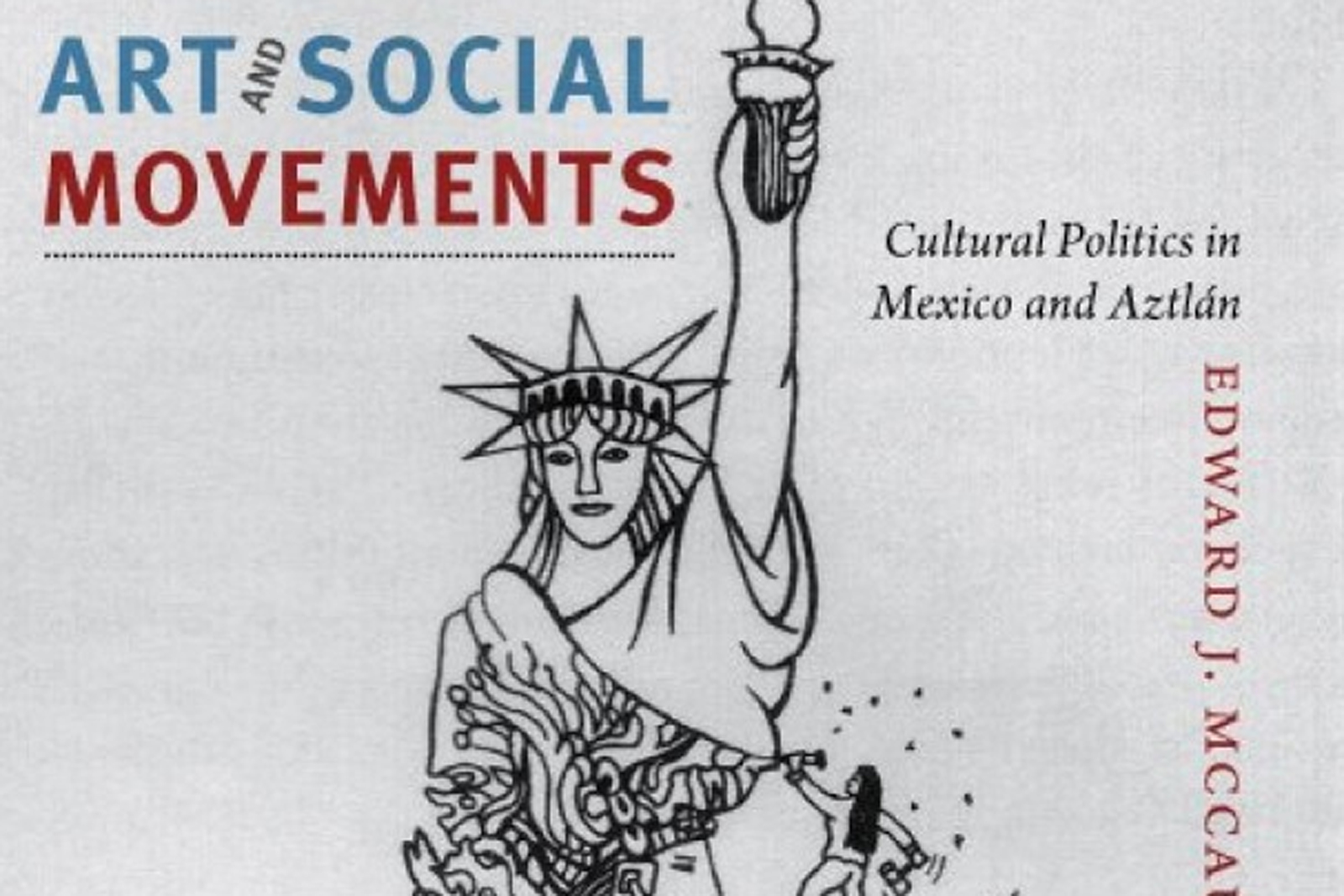

At the dining table, next to Hornitos tequila and Arizmendi pizza, sat a new book called “Art and Social Movements: Cultural Politics in Mexico and Aztlan.” One of the friends, Ed McCaughan, wrote it. The other, Maris Bustamante, is featured in it. The book wasn’t the center of conversation — daughters and new adventures in life were — but it was certainly one of the reasons behind the reunion: on Saturday, the two will speak on a panel at Galeria de la Raza about its subject.

McCaughan, chair of the Sociology Department at San Francisco State University, first met Bustamante in 1998 when he began researching the book. A Mexico City native and feminist artist, she was, and still is, considered by many “the godmother of Mexican performance art.”

The basis of the book is a simple question: What is the role of visual art in social movements?

To find, out McCaughan followed three movements that happened during the same time period in different locations, and in which art took on different meanings.

He studied the Mexican student movement of 1968, where activist artist collectives emerged; the Chicano movement of the 1960s in California; and the Zapotec indigenous struggle in Oaxaca through the 1970s and ’80s.

One of the main things he took away from his research was “how local context mediated the way they went about their movements.”

For example, said McCaughan, in Mexico’s 1968 student movement, anything associated with the state represented authority and repression, so protesters steered away from nationalist imagery like the eagle. But in the U.S. Chicano movement, such imagery represented pride and re-establishing connections to one’s roots; the eagle became a symbol of that. In Oaxaca, protesters resisted the domination of Mexico City and used regional images disconnected from mainstream Mexican history.

Despite the differences, McCaughan learned “how people imagined themselves as empowered citizens through art.”

Although Bustamante wasn’t connected to one movement, he considers her one of these people.

Through the 1970s, Bustamante belonged to two groups — Grupo No Grupo and Polvo de Gallina Negra — that redefined art and strayed from the traditional sense of the medium.

“She helped redefine not just the role of art but an approach to politics — that you could use humor, satire and irreverence as a powerful tool,” McCaughan said.

One of her most famous acts was when she wore a penis on her nose while deconstructing Freud’s theory of penis envy. It was, of course, a criticism.

“He was so macho,” she said.

“We were artists in Mexico that could penetrate political structures — that was my main goal.”

“We weren’t followers doing murals,” she added. “I am a conceptual artist.”

Conceptual meaning that she performs, like when she popped popcorn as a way of delivering eulogies; and conceptual in terms of breaking with traditional culture, not creating still images, and constantly experimenting.

“It opened new ways of thinking,” she said, ones that were against conventions like politics, marriage and the typical art market.

She didn’t identify with social movements because they were too mainstream, she said, although they gave her the support she needed at the time.

“Artists like her helped movements think of power in a different way; not institutional or political power but letting people understand the world and reality in different ways,” said McCaughan, who is from Gridley, California, a small agricultural town in the northern Sacramento Valley.

And this imagining of the world in different ways kept popping up as a theme in his research, and now in his book.

For instance, one image in McCaughan’s book comes from the Chicano movement, a mural in the Mission’s Balmy Alley created by a group of women called Mujeres Muralistas. No longer there, it was one of the first in the alley, painted in 1972, with images of water, flowers and plant life growing along the walls.

“The women defied the mural genre — this one isn’t the typical one with raised fists but of nature,” he said. “These women were intervening in the visual discourse.”

McCaughan fondly recalls one instance in which he came across some pieces of art from the Oaxacan movement, which proved difficult to document because there was so little research about it.

He was in Juchitan on the Oaxacan coast, which was center of the movement, when a local artist took him to the home of the widow of a “disappeared” militant. In a shed they discovered dozens of posters from the movement that were folded, torn and covered with dust.

One, a silkscreen for a literacy campaign, particularly struck him.

“It showed a woman in traditional Oaxacan garb sitting under a tree, with sunshine above her and letters falling from the sky. It was as if her thirst was quenched,” he said. “It was such a striking image.”

The images coming out of today’s movements are just as relevant and powerful, McCaughan said.

We’re still understanding what it means to be a woman today, he said, and what it is to stand up to the government, and what it means to be an empowered citizen. That, he added, could never have happened without artists.

For more information about Saturday’s event at Galeria de la Raza, click here.