It all happened while she was in the shower.

“I remember it exactly,” said Miriam Zouzounis, 13 years old on September 11, 2001. “My mom came in and she was horrified.”

Zouzounis, half Palestinian, half Greek, went to school that day. A comment directed at her still stings. “‘It’s your fault for everything,’” someone told her.

As the anniversary of the terrorist attacks approaches, across the country, residents are recalling the day – what they were doing, who they were with. As one Mission resident said, “now the world is different.”

Outside of New York and Washington, however, perhaps no group was as affected as those in the Arab-American community. For them – especially the adolescents – the distance between San Francisco and New York, matters little. For them, 9/11 was a day of reckoning.

It began Tina’s awareness of discrimination. Then 15, the 25-year-old daughter of a Middle Eastern grocer, remembers her brother returning early from school. “They sent all the Arabic kids home because they were afraid of what might happen,” she said.

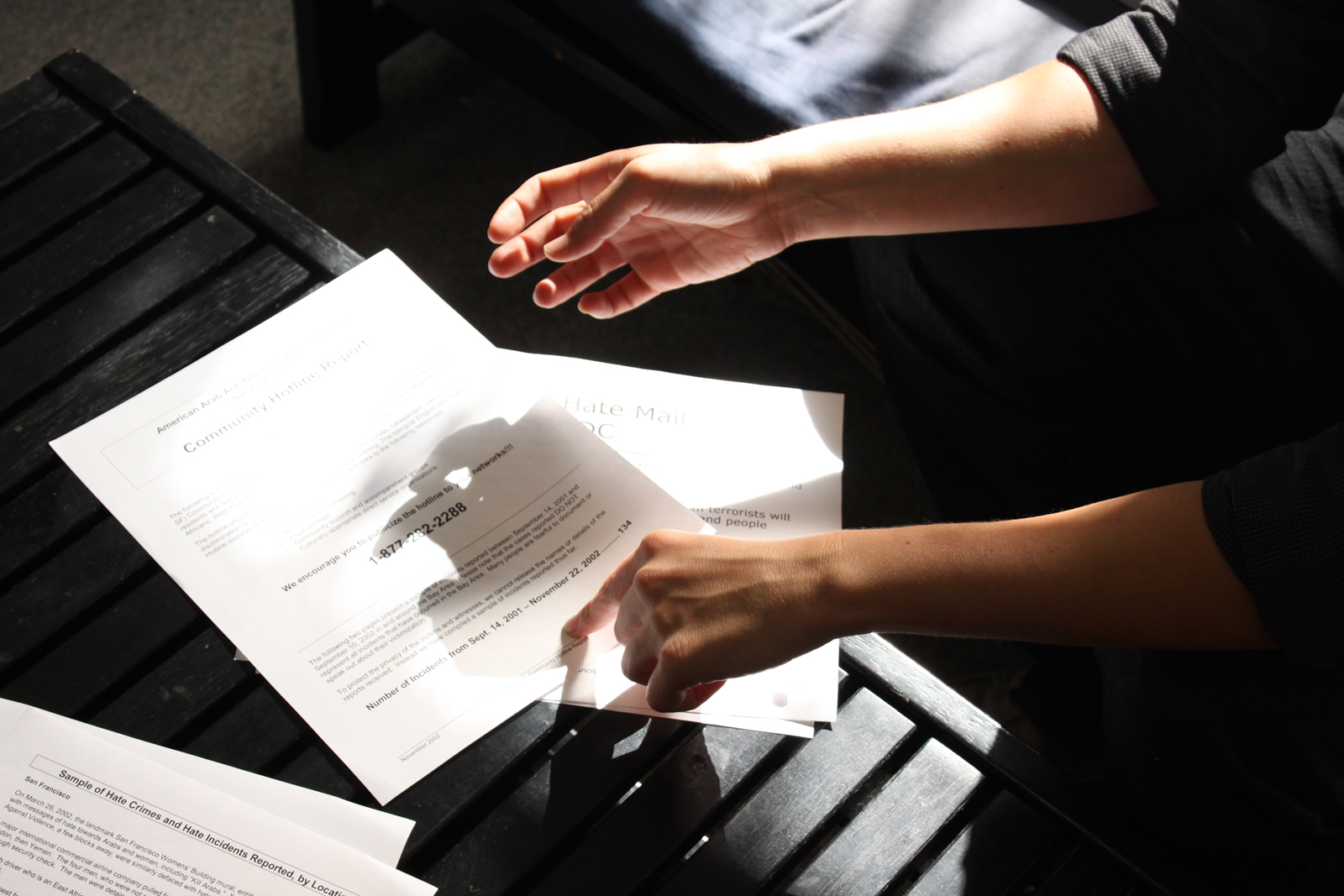

That night, a 24/7 hotline was created by the Arab Resource and Organizing Center, now at 522 Valencia St. “People knew there were going to be problems immediately,” said executive director Lily Haskell, 29. The center estimated in 2005 that there were some 120,000 Arab Americans living in the Bay Area, according to the San Francisco Chronicle.

Hate crime reports and discriminatory comments scrawled on napkins and post-its are now compiled in their incident reports binder.

“After September 11, someone actually came to the door with a pickaxe,” said Haskell. “They were coming to target our office.”

Samir Khoury, 75, owner of Samiramis Imports at 2990 Mission St., still gets threats. “Anytime something happens [involving Middle Easterners] I get a threatening call,” he said. One time he was so scared, he called the FBI.

His sales went down, too. “Maybe that’s one way they show they don’t want to support Middle Eastern businesses,” Khoury said.

Tina struggled as well. “It was really hard in the beginning because people automatically think just cause we’re Arab, we’re terrorists,” she said.

For others in the Mission, 9/11 stirs up memories of shock and confusion.

“At first I thought it was just an accident,” said Joe Readel, 26, a City College music student. “I didn’t realize how bad it was until I saw it on TV.”

Some, like Maddy Boom, would rather not be constantly reminded. “To be honest, I shut it out,” said the 26-year-old stage manager of Brava Theater. She can’t bear to think about the visit to her grandfather’s home in New York shortly after the attacks.

“His patio had three feet of ash,” she said. “It was really scary thinking that he was close enough that his apartment was covered in ash.”

Abigail Edber, a costumer at Brava Theater, was only 12 at the time, but old enough to know that things would never be the same.

“I just wanted it to be a normal thing,” she said. “I wanted the adults to stop crying, and I wanted it to go back to what it was.”

Her dad told her that there was no going back. “You know, I really want things to be boring again,” he said.

Twenty-year-old Caroline Kangas, who works at 826 Valencia, said her mother’s job in the scheduling department at Alaska Airlines reminds her that 9/11 didn’t stop on 9/11. “Every time there’s a heightened security measure, it changes the schedule and it affects her job,” Kangas said.

On 9/11 she got on the bus and went to school. “It was surreal in that sense.”

It was very surreal for Mayuma Hikita, 28. The City College student worked at a nursery in Japan. She was responsible for a four-year-old whose father worked in the Twin Towers.

The child’s mother picked the boy up immediately, and they fled to New York. Hikita never heard whether or not the father survived.

Some in the Mission said they didn’t understand what was happening. On his way to work in Mill Valley, Jorge Blanco, 62, saw a woman crying at a computer. “I was confused,” he said. “I didn’t speak English.” It wasn’t until 4 p.m. that he found out what happened.

Rohina Malik, an award-winning playwright from Chicago, was inspired to educate after 9/11. She brought her one-woman show “Unveiled” to San Francisco this week, eager to dispel hate stemming from fear and ignorance.

“My hope is that people will leave the theater seeing Muslims not as ‘other’ but as human beings.”

It’s disappointing to read that Palestinians and Arabs continue to face discrimination in San Francisco due to 9/11. I was hoping that we could see the bigger picture, be an exception to the mob mentality that has run amuck in the rest of the country and not paint everybody with one huge brush.

But that also invites thoughts about what can happen to any ethnic group when yellow journalism spreads hate, lies and jingoism.