It was just another creek map. Christopher Richard, a biologist and editor at the Oakland Museum, had been creating them for watersheds throughout the Bay Area. The one he started in the mid-2000s was for San Francisco. The survey data in front of him wasn’t quite enough, so he dipped further into research — poring over explorers’ maps and historical literature.

Particularly confusing was a body of water in the Mission Bay watershed described by explorers and drawn by some cartographers: Laguna Dolores, known popularly as Lake Dolores.

Richard studied at least 100 maps of the San Francisco peninsula drawn before 1912. None showed a large second body of water — most showed only the tidal inlet that had been navigable in the past up to what is now 16th and Harrison streets. Many maps showed the inlet as tidally connected; others drew no inlet to the Bay and simply inserted an isolated body of water, often titled Laguna Dolores.

Something didn’t feel right.

Richard wasn’t the first to doubt the existence of a freshwater lagoon in the Mission District. At the celebration of San Francisco’s centennial in 1876 it became the focus of a small debate. In 1942, George Merrill wrote a pamphlet titled “The Story of Lake Dolores and Mission San Francisco de Asis.” For his research, Merrill spoke with some of the oldest living Mission residents; one of them said he remembered a dock at 17th and Guerrero as a boy.

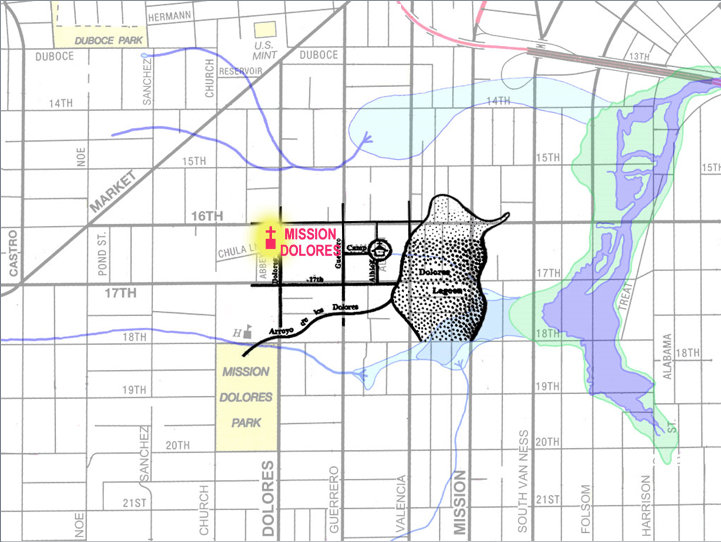

Richard considered all of this, but a deadline loomed. He and his co-mapmaker, geologist Janet Sowers, had to publish something. Sowers wanted to follow the detailed 1852 Coast Survey map that excluded the lagoon. But Richard was swayed by the historical accounts and a popular 1912 map by Zoeth Eldredge.

Sowers and Richard compromised. They drew in Dolores Lagoon, but not firmly. Whereas creeks and inlets and marshland were indicated by solid lines, a series of dashes represented the lagoon — a clue that its whereabouts was essentially a guess.

The creek and watershed map was published in 2007, but Richard wasn’t happy. For him, the dashes indicated unfinished business, a mystery unresolved.

“I’m not comfortable having published this sleazy-weazy broken-line indication of what was there,” he said recently. “I feel some guilt at this point of having drawn [that] map. I had an engendered determination to get it straight this time.”

So he began this project — now stretched to four years — to answer one question: Did Laguna Dolores ever exist?

“This has become a research obsession for me, in a sort of way nothing ever has,” he said.

Where Dolores Began

The original name, Dolores, and its hydrological descriptions, are rooted in paragraphs from the diaries of the Spanish explorers who founded the San Francisco mission.

Their journeys brought them to San Francisco when the Spanish government sent Juan Bautista de Anza to scout locations for a presidio and mission. Richard began there, too — digging up all 232 pages of de Anza’s elongated cursive field notes.

He looked at the paragraphs describing de Anza’s days on the San Francisco peninsula in late March 1776, in which the explorer mentioned three bodies of water.

One was Mountain Lake in what would become San Francisco’s Presidio, where he camped. Then, de Anza wrote, he found a good spot for planting crops that could be irrigated with water from the “ojo de agua o fuente,” a phrase that translates to spring or fountain. He wrote that entry as he was looking for a location to set up a mission and grow food to nourish his soldiers at the presidio.

The third body of water he described as a permanent “laguna,” and also as a “laguna de manantial,” or spring-fed pond.

The laguna “does not have any land which could be irrigated,” de Anza wrote in 1776 (translated in 1930 by Herbert Bolton), “because the tide of the sea overflows the lowlands there, but on the banks of the laguna good gardens can be planted.”

Richard says this topography describes the body of water later known as Washerwoman’s Lagoon near Lombard and Gough, where miners had their sweaty shirts washed during the Gold Rush.

“He talks about them [the water bodies] out of sequence,” Richard said of de Anza’s notes. “It’s a really difficult paragraph to parse.”

The next day de Anza again describes going to the “laguna de manantial” and “likewise to the ojo de agua, which I called los Dolores.”

The chaplain who accompanied de Anza, Father Pedro Font, described the journey on the same day.

“We arrived at a beautiful creek, which because it was Friday of Sorrows, we called the Arroyo de Los Dolores.” (Dolores is the Spanish word for sorrows.)

These two entries indicate that the water body named Dolores was either a spring or a creek somewhere in the Mission.

Much of San Francisco was vegetated dunes before development — not good for planting crops. The only good alluvial soils on the peninsula are in the southeast corner, today’s Mission District.

Richard believes that de Anza needed to find arable soil and an uphill water source, and that’s what he saw in the ojo de agua. But the ojo called Dolores, Richard believes, was a spring, not a lake.

Richard, a scientist with experience in hydrology and waterways, believes that the spring de Anza and Font found was near where Duboce and Sanchez streets meet today.

“It makes absolute perfect geomorphic sense that there was a spring there. The subterranean water coming through the dunes comes up on alluvial soil.”

The spring was the source for a creek that ran down Duboce, past the Mint, into seasonal marshlands that flowed near 14th Street to the tidal inlet. Water not diverted to sewers still flows underground there today.

The Settlers Arrive

The next mention of Dolores comes from Father Francisco Palou, who in June 1776 rode north from Monterey with soldiers, colonists, herdsmen, servants and their families to set up camp and a mission, following de Anza’s suggestions.

After a 10-day journey, where they encountered 11-foot-long elk and herds of antelope, Palou writes, “The expedition arrived near its destination. The commander [Jose Joaquin Moraga], therefore, ordered the camp to be pitched on the bank of a laguna, which Señor Anza had named Nuestra Señora de los Dolores, and which is in sight of the Bay of the Weepers and of the bay or arm of the sea that extends to the southeast.”

Out of the three journals, this is the first mention of Dolores as a lagoon.

Richard thinks that Moraga, Palou and their big group were coming in with horses and cattle from the south after a long journey. They saw the sand blowing and the wind whistling up ahead, and they decided to set camp on the ridge between two creeks (near 16th and Dolores), shy of the exact spot that de Anza and Font had declared a good place for a mission.

Richard believes they wanted to stay on higher ground, above two freshwater creeks — the one that flowed from the spring at Duboce and another that came off Twin Peaks and ran down 18th Street.

One reason to stay further up, Richard said, was that the willows down by the creeks were good stomping grounds for grizzly bears and mosquitoes.

Palou set up a hut, recited the first mass, and Mission Dolores was born. Of the two nearby creeks, he referred to the one on 18th Street, not the one flowing from Duboce, as Dolores Creek.

The Power of Maps

The 1852 Coast Survey — the one that was enough to convince Richard’s mapmaking colleague Sowers that there was no lagoon — was a thorough map, according to Richard.

“It was the first trustworthy map — everything else is essentially a sketch. They were out there dragging chains through marshes, getting tidal sloughs. It was days and days of work to map through the marsh.”

The Coast Survey was detailed and showed exactly where waterways were.

Another map, 60 years later, painted a different picture, and had a profound impact on all that would follow.

It was by Zoeth Eldredge, who wrote a book in 1912 titled “The Beginnings of San Francisco.” It included a map with the vanished lagoon drawn underneath the streets. It was labeled Laguna de Manantial — the same words de Anza used to describe Washerwoman’s Lagoon.

“The Laguna de los Dolores covered the present city blocks bounded by Fifteenth, Twentieth, Valencia and Howard streets, now closely built up with residencies,” Eldredge wrote.

Richard doesn’t believe Eldredge had real evidence or annotation to prove the map correct.

“He wasn’t snooping the navigational charts,” Richard said. “He was just quoting an early history book that was quoting an earlier history book” — a sort of early 1900s game of telephone.

Others agree that Eldredge’s map was a catalyst for incorrect history.

“That map was drawn in 1912 by a guy who misreads the diaries,” writer and historian Chris Carlsson said of Eldredge. “He invented a myth. There’s not really any prior evidence of a freshwater lake. Maps are usually drawn based on previous maps.”

Another reason the lagoon seems suspect to Richard is because the creek near 18th Street ran through a naturally formed 40-foot gully, mostly infill today. Wouldn’t water have drained into the gully and flowed out to the Bay?

Richard presented his research recently to the San Francisco Estuary Institute. The geomorphic scientists there engaged in a roundtable discussion. They tried to test scenarios for how the lagoon described by Eldredge could have been in that location in 1776 and not there in the 1852 Coast Survey.

They tested beaver dams, earthquakes and other ideas. “There wasn’t a single person who could come up with a theory that could possibly explain a body of water there,” Richard said.

Richard’s next map of the Mission Bay watershed, to be published this year, shows that parts of the Mission were very wet — the fresh water running off the hills joined with the tidal inlet, which would rise and fall. Areas between 17th and 19th streets, South Van Ness and Valencia could have standing water in heavy rainy seasons, but Richard describes it as at best “seasonal inundation” or “a splursh on your boots.” Not a lake.

Thanks for providing me with my next assigned reading as my Biology students and I at Mission HS continue our inquiry into the natural history of what went on before us and where do we go from here.

Mystery?

It is pretty well documented already, hardly a mystery.

Thank you sooo much for this article, and your perseverance!!! I am a Mission district Native, BORN and Raised here! Still here ALL 51 years lol!!

yes, but one confusion. Moraga says they camp on the banks of the lagoon DeAnza called Dolores etc. Richard says no, they camped on a ridge between two creeks. The article implies Palou built the first mission on a creek bank, although again, he refers to it as a lagoon, does he not? please clarify. also i would like to know more about the “small debate” during the centennial in 1876. my memory is that there was a reference to the lake having been filled in by silt and by the construction of market street. Do you have anything on that?

Re: Moraga (really Anza & Palou)

Neither Anza nor Font referred to a laguna in Dolores in their journal writings. At the end of his expedition, Anza was at the mission at Carmel for three days before heading south. Palou was there too. We will probably never know what conversations passed between the two, and how Anza might have described the place to Palou.

Re: Scale

Palou was traveling with a big party of soldiers, Hispanic settlers, Indians, cows, riding horses and pack horses, probably pigs and chickens. This party did not nestle-up to any landscape feature; they needed a lot of space to set up in. What does “near” mean? It is so relative to time and place. “Near” could have been anywhere that a padre or officer (the authors of the journals) could have said to a soldier or Indian “Go get me a drink of water from over there.” I’d bet that to these fellows, surrounded by what they perceived to be a vast wilderness, “near” was maybe a musket shot away, today that’s 2 or 3 bus stops away. Picture a creek running down 18th Street; couldn’t anywhere in Dolores Park qualify as on the banks of a creek if you were setting up camp for a large number of people and animals? We know that they did not camp at the water’s edge of the open water in the slough because it was flanked by wide salt marshes that would have been squishy underfoot, stinky, and pestiferous.

Re: Silt

Cattle, tilling the soil, construction, and other activities could have mobilized enough sediment to fill a stream course a few feet during the 75 years between the founding of the Mission and the first Coast Survey map – it is reasonable to assume that it did. But the canyon in which the 18th Street creek ran past Mission Street was 40-feet deep, and that canyon would have drained any pond as represented by the Elderidge map or the Camp & Albion monument.

I recently traced out the extent of the 18th St ravine/gulley based on the 1859 Coast Survey Map.

I don’t think people appreciate how deep it was. The best analogy I can give you is to stand at Guerrero & 27th, look north towards the depression that is Cesar Chavez, and imagine twice the depth in half the distance.

If you want to hear more details about this story, ask questions about San Francisco hydrology, or contribute your own thoughts and information about this story, I will be lecturing on this topic at the Randall Museum on the evening of April 21st and at Mission Dolores on the afternoon of June 25th.

Gee, there goes one of my favorite San Francisco stories. Thanks Hadley for a great article. I was not even aware there was a controversy but now it looks it has fizzled out. So the dampness in the walls of the Dolores Park Cafe (restrooms), is that because of the creek running beneath? That’s what I read a few years ago. I was convinced that creek had been covered after the Dolores lake disappeared. I’m going to have to rethink the history of that intersection now.

The 18th Street creek, the 14th/15th Street creek, the tidal estuary, and even the open waters of Mission Bay have now been filled as far east as Mission Rock. All this fill is a semipermeable dam that likely has backed up groundwater, perhaps even to higher levels than they had been primevally, in the Mission District. The bathroom walls are quite plausibly moist because of groundwater flow that would have drained away down the 40-foot deep gully in which the 18th street creek ran before the gully was filled. None of this necessitates that there had also been a freshwater lake.

Thanks Joel! And thanks for planting the seed of interest for this article.

Thanks Hadley, for a fascinating piece. And thanks Joel, for the Thinkwalks link — looks interesting.

Reading this I couldn’t help but pull out last year’s Anchor Steam calendar which, for the month of September, shows a circa 1870 panorama of SF (artist unknown) with familiar landmarks of the day. The lake is a major feature in this painting. Not sure what to make of that. See the painting here: http://www.anchorbrewing.com/beers/2002poster.htm

Neither I, nor no one that I have ever heard, has argued that there was not a tidal, estuarine body of open water extending as far west as South Van Ness and a salt marsh extending west to Capp Street. That is very well established by numerous incontrovertible surveys and maps. The question is: was there a second water body, a freshwater pond, between Mission and Guerrero, as shown on the maps by Eldridge in 1912 or on the historical monument at Camp and Albion? I am asserting that there is no reliable evidence or even plausible explanation justifying that second water body.

Now, working at Oakland Museum of California, where we strive to integrate the interpretation of both the art and natural history of California, we have encountered numbers of occasions where landscape artists have produced pastiches of scenes from various locations in one painting. But even without asserting artistic license, Hadley’s response is perfectly on point, that the artist is showing the tidal estuary, not a second freshwater pond.

The Anchor Brewing Co. poster is 1 I’ve referenced in several places, I feel it is a quite nice rendering of the marsh area as it expands south and west from the Folsom/Harrison 17th/18th area. The perspective is probably not as clear as it might be but the widening back slough/wetlands area shown on the Coast Survey maps have very similiar shape, but just some “artistic license” with perspective.

Hi David. The painting from your link is one often used in telling the history of Lake Dolores. It is pictured in “San Francisco: A Natural History,” by author and historian Greg Gaar.

The artist who painted it is unknown. Joel Pomerantz (who commented above and gives presentations on this topic) believes that the painting is based on a previous one that shows the body of water as the tidal inlet. The detailed coast survey from 1852 didn’t have a lake in that area.

Excellent article, Hadley! I was hoping that the hand of a journalist could make of this a compelling story, concisely and clearly told, and you did that. Thank you.

Of course, the fictional Dolores may still be retold in stories, and copied from fudged maps (even Janet Sowers and Christopher Richard’s), but at least this is a leap in the direction of illumination.

For folks who are interested in examining the map and photo evidence, visiting the places described, and putting it in the context of water politics and landform history, I invite you to one of my Thinkwalks on the subject.

Joel,

We’re hoping to get the go ahead from SFPUC this month to revise our map. For me it will be an act of contrition. If only we could get the first edition to self destruct!

I’d like to hear more about the presence of Grizzly bears in SF…

Anza & Font’s party report killing a grizzly bear near San Bruno Mountain on their way south from San Francisco. While traveling near San Leandro, they also remark about seeing many Indians disfigured by bear attacks. I suspect that the wide berth El Camino Real gave the neighborhood now known as “willows,” just east of downtown San Jose, represents an aversion to the proximity of grizzlies — mosquitoes too.

Wow. I’ve always wondered. Thanks!

Couldn’t “put it down”! I was supposed to be on my way to a meeting but stayed to finish reading the mystery.

Thanks for an excellent informative article.

You might consider the spring and group of 4 bodies of water called Lake Merced. Back then there would have been 3. The 4th today of for reclamation. It has elevated sides that you could plant gardens on and the Ocean flooding the low land right next to it. It is on the way toward the Presidio as well. It had a creek connected to it called Stanley Creek which was piped in the early 30s when the built Stanley Drive which today is called Brotherhood Way. You will find all sorts of granite and cobble stone buried everywhere around the area. Plus foundations of long gone buildings. Enjoy⧊⨻𐓚