Then, as now, they came to the Mission to party. In all of San Francisco, the Mission had the most water. And that meant one thing: beer.

“If you want to look for where the water was, look for the breweries,” says Chris Carlsson, a local writer and historian.

This ride is part of an enthusiastic, highly opinionated series of bike tours organized twice a year by Carlsson. As he pedals toward the Mission on his well-used mountain bike with a public address system strapped to one side and a bucket of maps strapped to the other, he points to the Costco at 10th and Harrison. It looms over our group like a gray and well-secured fortress of bulk savings. “That was the Falstaff Brewery. It was built right next to Mission Creek.” The crowd of urban planning wonks, curious Google employees and local history buffs peer up. It could (technically) still be considered a source of beer. There is no sign that it was ever surrounded by anything other than a concrete tangle of highway off-ramps.

“You’ve got to understand, these creeks smelled bad,” says Carlsson. “Wetlands don’t smell great even when they’re healthy, but so much sewage ran into them that by the time they were covered, pretty much every creek in San Francisco was nicknamed ‘shit creek’”

As Berkeley continues with plans to daylight Strawberry Creek in its city center, and Los Angeles reopens sections of the Los Angeles river that once flowed through sewage pipes, curiosity about the Mission’s buried waterways is high.

San Francisco’s abundant water supply becomes dramatically evident during the rainy season, when buildings flood and the city’s sewage system overflows. To the Public Utilities Commission daylighting a few creeks would potentially be less expensive than expanding the sewage system (though the PUC’s daylighting plans run more to concrete culverts than full restoration). And local writers like Joel Pomerantz put forward dramatic but thought-provoking theories about the potential long-term environmental and financial benefits of using more of San Francisco’s own water supply.

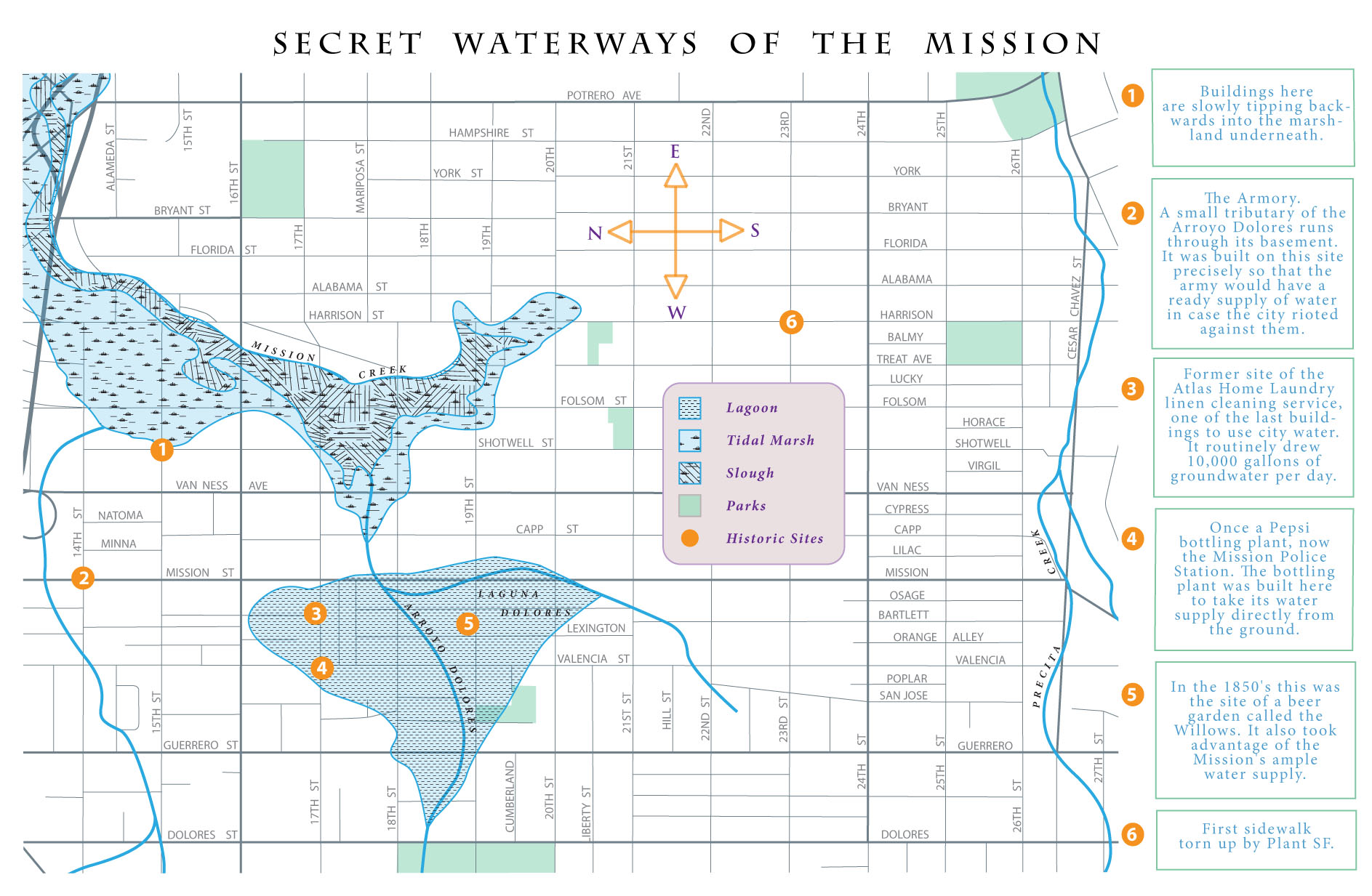

The Arroyo Dolores ran down 18th street. Precita Creek ran down Caesar Chavez to the vast marshland on the other side of Bernal Hill. The Armory, at 15th and Van Ness, was built over a tributary of Mission Creek, so that it would have its own water supply in case the National Guard was ever put under siege by a rabble-rousing populace. And a lake, whose exact location is still a matter of debate, most likely stretched between Mission and Valencia, and 20th and 16th streets before being filled in with sand. It wasn’t necessarily done well – at 15th and Shotwell several buildings tilt slowly backward like party goers after a long night.

A massive beer garden called The Willows stretched from 19th and Valencia and 18th and Mission in the 1850s. A Pepsi-owned bottling plant at 17th at Valencia used city water to make soda. It was sold in the 1970s, and is now the site of the Mission Police Station. And the long-lived Atlas Home Laundry linen cleaning service at 17th and Hoff drew 10,000 gallons of groundwater a day until it was replaced by a recent development.

The history of water in San Francisco is a history of scandal and monopoly. Anyone who looks up the terms Spring Valley Water Company and Raker Act will have enough reading material to leave them cross-eyed. In short: only a few older buildings still use water from the supply directly under the city, instead of water piped down from the Hetch Hetchy reservoir in Yosemite.

Mostly San Francisco’s water is a secret to all but a few. The Civic Center BART stop has pumps going day and night to keep the underground tributaries of the Hayes River from flooding the tracks – 2.5 million gallons of tested, high-quality groundwater sent straight into the sewer system, because the city has yet to figure out a way to adapt its old sewer system to separate out clean water from waste. The only place where residents actually encounter the Hayes is via the public fountains at United Nations Plaza and Fillmore Center – their water is Hayes water.

The Mission Dolores itself, in all of its squat, stuccoed glory, was erected near the banks of the most mysterious body of water in the Mission – the elusive Laguna Dolores. Certainly, someone filled it with sand, but its exact location before then is a matter of some dispute. The only thing that Carlsson and Pomerantz are sure of: the historical marker at Camp and Albion depicting the site of the lake seems to be inaccurate. Or at least neither, in the course of their research, has been able to find a primary source that convincingly supports that location.

The Mission was damp and hard to traverse. A plank road was built to move goods in from the waterfront (and to charge people for the privilege of doing so – it was a toll road). It was difficult to sink pilings deep enough to support the road, and it continued to sink further down long after it was built.

As Carlsson’s tour prepares to exit the Mission for the not-so-secret waterways of the Bayview, he stops by 23rd and Harrison, next to a few innocuous rectangles of dirt with flowers and spikey plants growing out of them. Here, he says, is one of the gardens put in by Jane Martin, a local landscape architect who in 2004 persuaded the city of San Francisco to simplify the permit process so that residents could petition the city to tear up pavement and plant gardens. Just a few decades ago, says Carlsson, San Francisco was a cement city. Organizations like Friends of the Urban Forest and Martin’s group, Plant SF, are a relatively recent development.

It’s an aesthetic move, and a bribe to the rain – giving it a chance to rejoin the aquifer beneath the Mission, and hoping that it goes there instead of into your basement, or out in to the bay. After all this talk about waterways being shifted around and constrained, it feels a bit open-spirited. “This,” Carlsson says, “is spot where people began to think about returning water to the city.”

Click here to download a PDF of Mission Local’s Secret Waterways map

First off, The Armory is on the northeast corner of Mission and 14th Street. I’ve seen the water flow in the second basement.

I always thought that Laguna Dolores was centered around 17th/Folsom-Shotwell, because that’s where the water pools during flood events. The 18th Street and 16th Street creeks fed that as did some of Mission Creek.

I like the idea of letting rivers run through our cities again. Now if we could figure out a way to pave parking lots with something that would let the rain through to the soil beneath.

Permeable pavement has been around for awhile now. And yes to daylighting creeks!

fascinating! I love learning about how the City was before we started ‘citying’ it!