What does compassion toward people in crisis look like?

After her 15-year career as a San Francisco EMT and paramedic, Joanna Sokol is more confused about the answer than ever before.

Is it compassionate to force someone to conform to your idea of a healthy lifestyle? Or is it compassionate to respect someone’s autonomy and let them die on the street? Is it compassionate to push troubled people out of sight so that everyone else feels better?

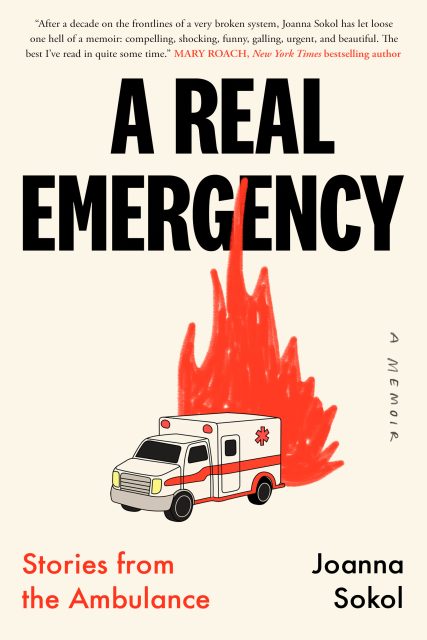

For any option you choose, Sokol has a story that will make you reconsider. She shares these sometimes poignant, sometimes absurd, and always very human experiences in her new memoir, “A Real Emergency,” published by Strange Light, a Penguin Random House trademark.

“This place is like scary Narnia,” a patient once told her. Sokol was having a day where everyone seemed to be high on methamphetamine, agitated, confused, incoherent or angry. “Ma’am,” she said. “You are absolutely right.”

Being the person others turn to when they have no one else to call is often unglamorous, Sokol said in May while sitting in the Panhandle, a few blocks away from where she now teaches EMS classes at City College of San Francisco. It also changes how you think.

As she talked, Sokol played out how she’d hypothetically transport the joggers that ran by to the hospital. When a passerby dropped a blanket, she darted across the park to rescue it.

But she also paused to admire a Saint Bernard lumbering by with his frail, elderly owner: “They must be the best of friends. Can you imagine them just hanging out together? Having tea and biscuits?”

It’s this appreciation of camaraderie that helped Sokol write with compassion in spite of her confusion.

This interview has been edited for brevity.

Mission Local: In her essay “On Keeping a Notebook,” Joan Didion describes jotting down overheard quotes. You mention doing the same thing while taking down patients’ vitals. Is there anything someone said to you as a medic that has stuck with you?

Joanna Sokol: It’s funny, because the first couple that jump into my head didn’t actually make it into the book and are totally not appropriate for Mission Local.

ML: Now I want to know.

JS: I always remember this guy telling my partner, “You baby-Jesus-looking motherfucker.” Whenever somebody does something dumb, in the back of my head I just go, “You baby-Jesus-looking motherfucker,” because it was the funniest insult.

There were so many intense experiences flying around me all day. I started writing stuff down, to feel it was all going somewhere instead of just whooshing by me. It helped me feel a little bit less lost.

ML: The first quote that came to mind was someone getting angry at you. I imagine that happened often. How would you deal with that?

JS: A lot of the time when folks think about being a medic, they think that the most intense part of our job is people dying or bleeding or being in pain. It’s just not. A lot of the heaviness of the job is just dealing with the extremes of human emotion all day, every day.

Most patients are not clean-cut, relatable people who have a sudden emergency. It’s folks who are elderly, who are chronically ill, who are unhoused. It’s mental illness, domestic violence, and addiction issues.

A part of our job that is, unfortunately, very useful for a lot of these people is being a punching bag. You try to understand that it’s not actually about you, it’s about the system. People are suffering, and need somewhere to direct all their pain and frustration.

One of the ways that I processed it was admiring the way that they used the English language instead of trying to take it personal. The other big thing that we use to get through it all is camaraderie.

But there’s only so much screaming that you can take before you physically run out of the hormones and chemicals that protect you, and you start to lose your ability to regulate. That’s why medics should get more vacation time. When we have a little bit more time off to regulate our chemicals, then we’re better providers.

ML: Patients are both physically and emotionally vulnerable with you. That reflects one of the themes of your book: The blurred line between physical and behavioral health. How should people think about this connection?

JS: Your physical health is incredibly tied to your social status, financial health, and trauma levels.

Folks who don’t have reliable housing are going to have a really hard time getting their medicines on time. If you have a kidney problem and you’re supposed to go to an appointment to get your levels checked every other Tuesday, and that appointment is across town and you don’t have reliable transport, you’re not going to be able to make it there. So then your levels are going to get all screwy, and you’re going to end up in an ambulance.

We are the last resource that is available to people with no one else to call.

ML: We’ve written about a lot of these issues around 16th and Mission streets. There are people suffering on the street, and also neighbors who are tired of seeing the suffering. I imagine they’re feeling a compassion fatigue similar to what you describe in your book. Sometimes that frustration turns into anger. What do you think about all this?

JS: On the one hand, on the ambulance, I spent tons of time every day dealing with folks that are living outside and talking to them. Unhoused folks in San Francisco are not a homogenous bloc. Different people have different reasons for being outside. Some of them are real jerks, just like people who live in houses. Some of them are really cool.

On the other hand, I totally understand what it’s like to be frustrated and feel unsafe when you’re trying to walk down the street with your kids, and there’s poop and needles everywhere.

There’s a woman who was really, really sick outside for way too long. We kept trying to talk to her, and she kept running away from us. If we had forced her to go to a hospital and get evaluated about six months earlier, she would have probably been fine.

Instead, we left her outside rotting on the street, half-naked, slowly dying of an incredibly preventable infection that could have been treated if we had done what a lot of people think is inhumane.

Living or working in San Francisco forces you to ask these really intense questions about homelessness and behavioral health, and what safety means and what compassion looks like. I thought that after spending a year or two on the street crisis team, I would have a better answer.

Instead, I am more lost than ever. I have no clue what is right and wrong.

Is it compassionate to take people’s autonomy and try to force them into what you think a healthy lifestyle looks like?

Is it compassionate to let people live in horrific, painful circumstances where they slowly die when maybe they could have been helped?

Is it compassionate to make them all go away so that maybe they live somewhere else and our city feels a little bit externally safer and happier?

I didn’t get any closer to finding an answer to those questions. If anything, they got more complicated, because now I just have more examples of ways that all of the answers are wrong.

ML: How would you make decisions about when to force someone into care?

JS: As long as you’re alert, oriented, lucid, and coherent, you have the legal right in America to make stupid decisions that are going to kill you. We will often call extra people on scene for a second opinion, but a lot of the time it just ends up being a gut check.

ML: Housed residents are sometimes afraid of people living or using drugs on the street. Has your time as a medic changed your feelings about this population?

JS: It’s been almost a bell curve. When I first started in EMS, I became much more comfortable talking to all different kinds of people, and it was fun and interesting. I was like, “You shouldn’t be scared, these are just folks that use drugs. They’re not going to murder you.”

The longer I went on, it became trauma after death after trauma after violence after assault after death. After about a decade, I started to become more paranoid again.

ML: Has your time as a medic impacted how you see people in general?

JS: You’re always preparing in your head for the worst thing to happen.

If I see somebody with a limp or swollen ankles, I’m going to register that. If I see somebody that’s a little bit elderly, I’m always kind of ready for them to trip and fall over. If I see a dog that looks hyper, I’m always playing out scenes in my head like, what if it runs into the street? And then its owner tries to get it and a car hits them?

ML: Do you think anyone could be an EMT or a medic?

JS: Maybe. There are certain physical requirements. Like, if you’re blind, I don’t think you could drive around. Emotionally, I don’t know. People say all the time, “Oh, I could never do your job.” I say, “You could, if you had to. You probably never put yourself in that situation.”

ML: What did you learn about your work only while writing this book?

JS: The other day, someone asked me what the most surprising thing about writing the book is. I said, “You can have beer while you write.” Being able to sleep, eat and go to the bathroom was a revelation.

As I kept rewriting, my editor and mom (Sokol’s mother, Cynthia Gorney, was a reporter and South America bureau chief at The Washington Post) helped me find the love again.

I was an EMT for three or four years, and then a medic for almost 10. The first five or 10 years I did the work, I really loved it. Towards the end, I started to get so crispy. So I had to dig down deep and find compassion and humor again.

“A Real Emergency” by Joanna Sokol (464 pages, Strange Light, $18).

Excellent interview! Thank you for this. I appreciate the way you let her talk and didn’t editorialize.

Great article! Appreciate Joanna’s insights. And another well written piece by Abigail.

“I’ve seen it all”? That’s not experience talking, that’s arrogance. In EMS, there’s always something you haven’t seen. Every shift can throw something new, strange, or straight-up unbelievable your way. Even after decades in this job, you’ll still get humbled. So yeah, this article lost me at the title.

The old DPH medics are the real OGs and could tell you stories. I said to the husband and wife team, “I never have done CPR.” The husband goes, “Well, this will be a first.”

i love the interview! from a former emt and now crisis counselor in SF. i just requested that sfpl acquire the book 🙂

Anyone know a local bookstore in the Mission that’s carrying the book? Would love to grab one soon!