What do brain-eating amoebas, a grandmother’s google search, and a treatment for urinary tract infections have in common?

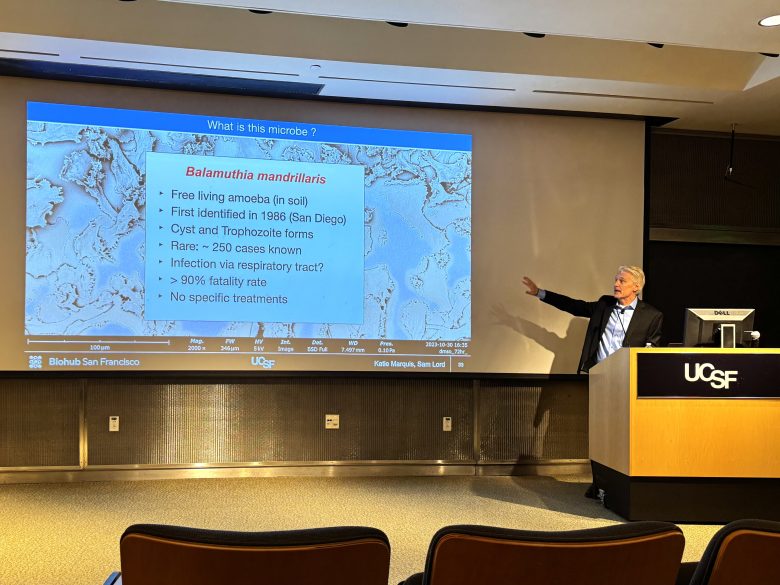

A lot, according to Joseph DeRisi, professor of biochemistry and biophysics at University of California, San Francisco, who unpacked the future of researching rare diseases at the University of California, San Francisco’s inaugural public-lecture series.

Hosted by UCSF’s department of Basic Sciences, the quarterly lectures are designed to make scientific concepts more accessible to the general public. Admission is free for everyone.

During his talk, DeRisi, who is a member of Mission Local’s board, sought to engage the non-scientists in the audience through interacting with them.

“If you live in our neighborhood, you walk by these laboratories, you probably wonder, what goes on in these laboratories? What do they actually do? Where are my tax dollars at the NIH really going?” said DeRisi at the lecture, held at UCSF’s Genentech Hall in Mission Bay. “This is an opportunity to engage with you.”

Most of the 50 or so attending the lecture were researchers, but about one-third of the audience had no scientific background.

Dr. Geeta Narlikar, Chair of DeRisi’s department and who has known him since they were graduate students together, introduced DeRisi as an “inventor and real-life virus hunter” with a childlike curiosity.

DeRisi’s lab uses genetic techniques to study infectious diseases. It also identifies viral or other agents behind diseases with unknown causes. Early work in his lab led to the identification of the SARS virus in 2003, and the lab was instrumental in building a free clinical testing lab during the COVID-19 pandemic.

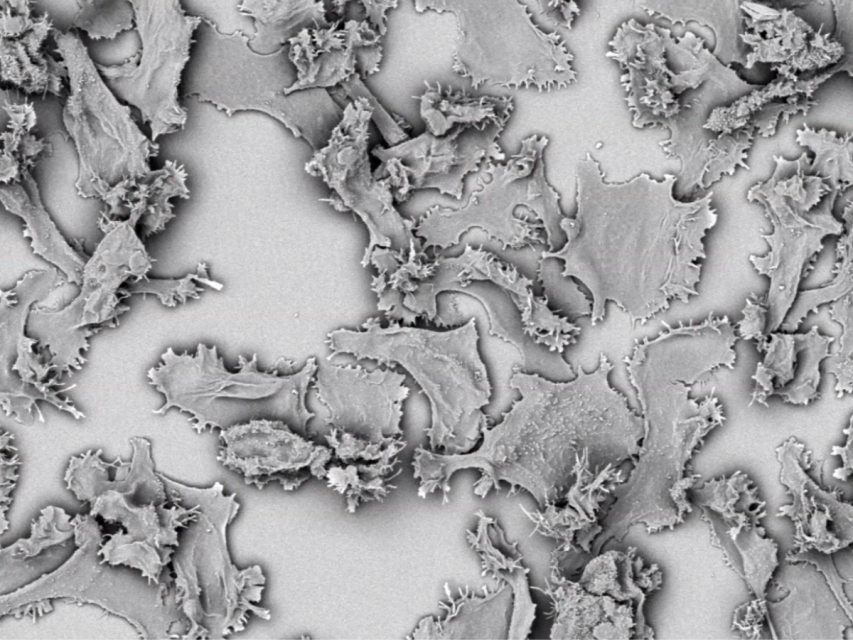

In his hour-long talk, punctuated by audience questions and more than a few laughs, DeRisi outlined his lab’s decade-long journey studying Balamuthia mandrillaris, an organism commonly known as a brain-eating amoeba because it causes severe brain inflammation. It is rare, but fatal and often goes undiagnosed.

Balamuthia, quite commonly found in soil, is harmless in small quantities. DeRisi assured the audience that the amount of Balamuthia required to cause brain inflammation is extremely high — like a child having a block of soil stuck up their nose for many hours.

At that time, there was no treatment other than empiric antibiotic coverage. The latter requires pumping the patient with several different antibiotics and hoping for the best, “because you don’t know what is wrong,” said DeRisi.

DeRisi believes that with genetic sequencing becoming increasingly affordable, the best approach to identifying malicious agents is to take a sample from the patient, like spinal fluid in the case of Balamuthia, and sequence all the genetic material in it, a process known as metagenomics.

Most genetic material, like DNA or RNA, will belong to the patient. But some, maybe 0.1 percent, might belong to the disease-causing organism.

Once the disease-causing agent has been identified, it can be subjected to in-depth research, said DeRisi, breaking down several complex experiments done by various members in his laboratory into accessible chunks.

The paradox with rare diseases, said DeRisi, is that funding is essential to research them and find treatments, but organizations like the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are not incentivized to do that, because the disease affects very few individuals. There is no market for a treatment targeting an extremely rare disease.

In such cases, scientists generally perform a “drug repurposing screen,” where they experiment with drugs or materials that are already approved for treatment in the United States, Europe or other countries, to see if they help control the rare disease being studied. If one works, there is no need to discover a completely new treatment.

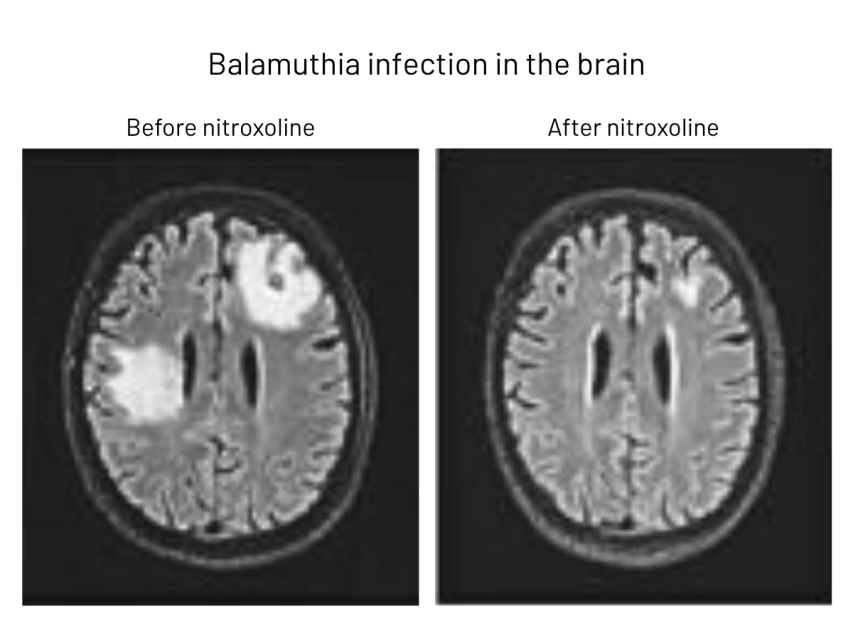

With a repurposing screen, Matthew Laurie, a graduate student at DeRisi’s lab, found that the compound nitroxoline was effective against Balamuthia. Nitroxoline has never been approved in the United States, but is used in Europe to treat common urinary tract infections.

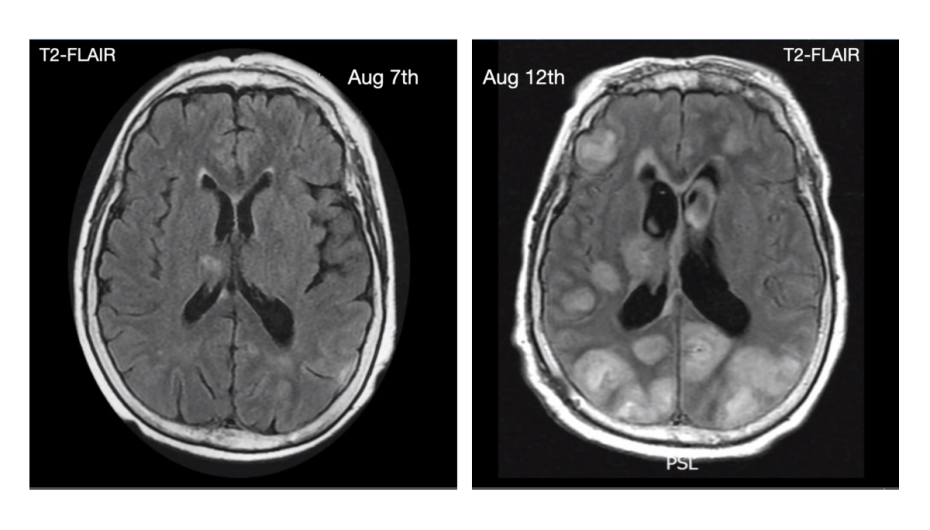

Over a few years, DeRisi’s lab had the opportunity to test nitroxoline, with emergency Food and Drug Administration approval, for dire cases of brain inflammation caused by Balamuthia. The results were positive. DeRisi credits Heather Stone from the FDA for her advocacy in getting patient approvals.

These were not clinical trials; they were singular clinical cases, DeRisi noted.

They included a man in his 50s, seizing with a Balamuthia infection, and a six-year-old child, originally thought to have brain cancer, who turned out to have Balamuthia.

The child’s grandmother found the preprint of DeRisi lab’s use of nitroxoline. (A preprint is a non-peer-reviewed scientific paper released online before journal publication, allowing early access to new findings.)

Now, as a result of this research, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention always has quantities of nitroxoline on hand for patients with a severe Balamuthia infection. This, said DeRisi, is a significant improvement spurred by metagenomics to identify the cause of such infection.

Kaitlin “Balamuthia whisperer” Marquis, a staff scientist in the DeRisi lab, continues to research the organism. DeRisi presented her research, which clarified Balamuthia mandrillaris’ genetic sequence and how nitroxoline acts on the organism.

After the talk, attendees had the opportunity to tour what DeRisi called the “toy room,” a place with genetic sequencing equipment, high-powered microscopes and other biotechnology machines. Eric Chow, director of the Center for Advanced Technology at UCSF, led the tour.

Everyone is born a scientist, said Narlikar.

“What’s different about us here at UCSF is [that] we’ve just been given the opportunity to use our curiosity to make an impact for bettering human health,” she said.

I hope the lectures find their way to a YouTube, other channel or Zoom meeting.

This is a great opportunity for the curious mind. Please publish a link to sign up for future lectures. My husband and I would love yo attend

If you would like to receive email updates and invitations related to The Science Scoop, please contact stephanie.sia@ucsf.edu to join the mailing list.

Yes, a link to the lecture series would be very helpful.

“This quarterly series aims to help people understand the human impact of scientific research.”

Republicans hate science so they won’t attend this.

On the other hand, attendance numbers won’t be affected much by their absence because Republicans are only 7% of San Franciscans.

So where is an actual link to sign up for the mailing list for future lectures?!

DDG returns https://ucsftalks.com/

All Basic Science talks start at noon – expect to see a lot of gray and white hair I suppose.

For real how do we go to the next one????

Surely a designated “science nerd” can wield a google search…