More than a decade ago, filmmaker Mimi Chakarova began following a cohort of young people trying to turn their lives around by becoming firefighters and medics through Bay EMT, a free training program.

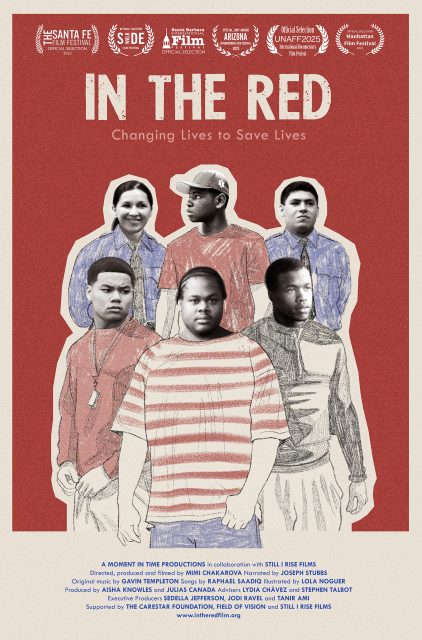

The result of that relationship-building, “In the Red,” shares their stories and the way they intersect with sweeping social issues like crime, public health, poverty, and inequity in a documentary that has the intimacy of a home video.

Bay EMT’s cadets, many of whom were involved with the juvenile justice system, have firsthand experience with the problems they’ll be asked to address as first responders. Their pasts both hinder and motivate them. Some go on to save lives. Others don’t make it.

Chakarova captures cinematic scenes, like Bay EMT director and firefighter Wellington Jackson running into a burning building. But it’s the more mundane personal moments, all filmed by Chakarova herself with no crew and a cash budget of less than $250,000, that make “In the Red” unique.

One trainee, Justin Mayo, describes how, when he became a teenager, people would go out of their way not to sit next to him — a young Black man — on BART.

“People would rather stand up for 45 minutes than sit down next to you,” Mayo says in the film. That changed, he added, when he put on his cadet uniform.

“Me having a uniform on portrayed me as someone who can possibly be a hero, or something.”

Chakarova is a longtime contributor to Mission Local, and a former board member. Mission Local’s founder Lydia Chávez served as an adviser for the film. Recently, Chakarova talked with Mission Local’s criminal justice reporter, Abigail Vân Neely, about what it’s like to meet a group of strangers, build trust, and follow their lives for over a decade.

“In the Red” will be screened at the Grand Lake Theater in Oakland on Monday, Sept. 22, 2025 at 6:30 PM. All proceeds will go toward Bay EMT. You can buy tickets here.

This interview has been lightly edited for brevity.

Mission Local: San Francisco is selecting a new police chief, and there have been a series of community meetings where residents can give input. A common sentiment attendees share is that they don’t feel safe.

You spent years with young people who described strangers feeling unsafe around them. What do you think about this?

Mimi Chakarova: A large reason why we make documentary films is to show a different reality, and to explain to people that this kind of perception does a lot of harm to a young person.

What people were seeing when Justin Mayo was sitting on BART was someone who was not safe to sit next to. They did not see him as a kid. They saw him as someone who could potentially harm them. But if he had a uniform on, that would give him the credibility to deserve respect.

ML: On the note of subverting expectations, one of the Bay EMT graduates Samantha Soto says she was homeless while she was working as a homeless outreach worker. How many people trying to help others on the streets have a similar story?

MC: A lot. Some people lose their jobs after many years of working. Some people are disabled and are no longer able to keep a job. Samantha was sleeping on couches for a long time. And then she slept in her truck. I think one of the reasons that she worked in the Tenderloin is because she could relate to the pain she was experiencing herself.

In the scene where she walks through the Tenderloin, she wasn’t wearing gloves or a mask. I love the fact that she wasn’t following protocol. I love the fact that she was physically feeling this man’s hands. The human interaction that you see in that scene is beautiful and remarkable.

If you have first responders who have experienced poverty, they’re going to approach the people that they’re helping on a completely different level. Samantha doesn’t judge them because she knows exactly where she was a few years back.

ML: How did you decide how much to reveal about someone’s personal life?

MC: I always equate it to being at a bus stop and having someone sit next to you and tell you their whole life story. They start telling you details from their life that could be really heavy, and you’re just not ready for it. When I structure a film, I think about what is too much, too soon.

At the same time, you don’t want to waste too much time before you get to the essence of what someone is dealing with or experiencing.

In the scenes of Julio Leon in the Mission, it’s the first time you meet him, and it’s important for you to know where he grew up and what he’s facing on a daily basis. The reason he’s chewing gum and looking behind his back a lot is because it’s late and he’s watching his back. I’m alone. I have a camera. He knows all the issues that can come up, because we’re filming. He’s street smart because he has to be.

It’s a very short introduction of him. Still, you pick up on all of his body language, his nervousness, his resolve.

Leon says, “You see a lot of shootings out here, but that’s just the way it is.” That statement says a lot from a young person. He’s not saying, “That’s how things are, but it really needs to change.” He knows the reality of how and where he grew up.

ML: At different points in the documentary, people you interview say that they don’t like talking about their feelings. How did you get them to agree to years of filming?

MC: One of the advantages that I had is I didn’t have a crew. It was just me and the camera. That’s it. I think it was very disarming because there was no element of intimidation; it was just much more raw.

I remember meeting with Wellington Jackson, who is the founder of Bay EMT, in August 2013. I told him I would need to go to participants’ homes. He told me, “This will never happen.”

I said, “Well, I can’t make a film if I cannot show footage of them brushing their teeth and going through their routine and have that type of trust. Because then it will just be about a program. And who wants to watch that? It’s boring. There’s a million films about nonprofit programs that do work in the inner city. I’m not interested in that.”

We thought that it would take two or three years, and that it would just focus on three people’s lives: Joseph Stubbs, Dexter Harris and Justin Mayo. I would film the EMT class, which is a five-month program, and then after the EMT class there is the fire program, which is another five months.

I thought I could follow these three individuals for ten months and then follow them the next year and see how they do. I started filming in 2013, and by 2015 we had a Hollywood ending. Everyone was doing great.

A couple of years later, there is a series of events that show the trajectory of success is not linear. People have setbacks that can completely derail them. The reporting needed to continue. The big question was, would they still let me in?

The shocking thing for me was that they never closed the door. And believe me, that door took a very long time to open.

ML: How did you blend into the background while filming?

MC: Physically, you put your body in the tiniest little spaces and corners. People use the expression “fly on the wall.” I would rather just be a piece of furniture. The more time you spend with people the more you become invisible.

I love the juxtaposition between the serious and the really silly. That’s what makes you close to the people you see on screen.

In the scene of Stubbs driving with balloons in his car he’s singing along to this intense song, but he’s also got all these damn balloons and he’s just trying to fling them out of his face so he can drive.

ML: How did it feel to watch people not make it through the program?

MC: There’s the conventional success story: You finish a program, you get a job, you buy a house and have kids. Not everyone is going down that path.

I was looking at a picture the other day and wondering, “What happened to this kid?” Jackson, the director of Bay EMT, said he got shot. He’s gone. He’s dead.

The documentary is only 94 minutes long. Imagine all the stories that you’re not hearing. Imagine all the kids who drop out after three weeks of class because their mom is addicted to drugs, or because they’re raising two kids and they have to get a job and don’t have time to study.

Sometimes success is just staying alive and getting up in the morning and leaving your house and trying again. The great thing about Bay EMT is that the door never shuts. Hopefully you see in the film that even people who don’t make it the first, second or third time can still return if that’s what they choose to do.

ML: Jackson says one of his goals with the program is to show the participants a different life. I imagine being part of a documentary also showed them something different. How did they feel about putting their lives on camera?

MC: Stubbs had never done narration. I remember bringing a paragraph to Sacramento and getting into a closet because we didn’t have a professional sound studio. I brought my recording gear.

The moment I heard his voice read the intro at the very beginning of the film, “A lot can happen in ten years,” there was no doubt that he had everything it takes to do this. I wrote the script from hundreds of pages of transcripts I went through to see exactly how he would say certain things.

The people who are most intriguing, genuine and altruistic are the people who never get to tell their stories. They have never had the desire to be in the spotlight, because they’re too busy doing the work. Jackson hates being on camera. It took me two years to get him to sit for an interview.

ML: How did Stubbs and the others respond when they first saw the documentary?

MC: They loved it. When we had our official premiere in Santa Barbara in February, they all came.

We’ll have smaller screenings in the future, like at the New Parkway Theater in Oakland and The Roxie in the Mission. But I thought for our first community screening, having it at the Grand Lake with the firefighters and local leaders would be best.

There is so much negative coverage surrounding Oakland. I wanted to create something that shows you that change is slow, but having people mentor you can really go a long way.