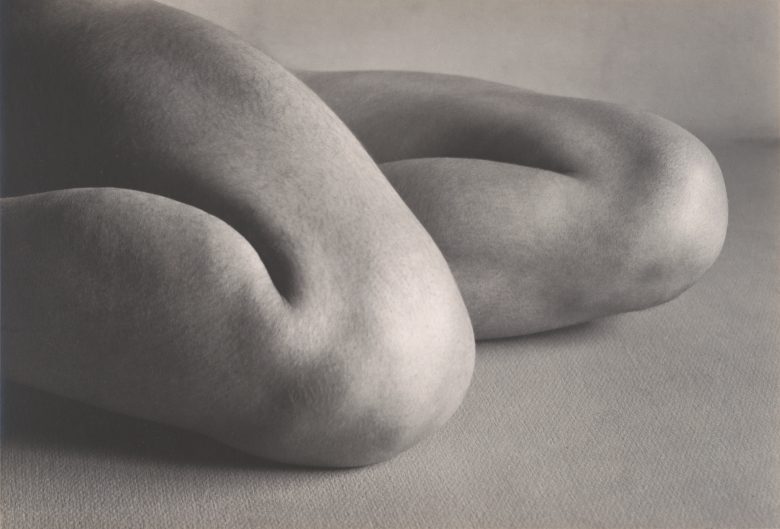

In 1932, eleven Bay Area photographers — among them Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams — changed the history of photography.

Under the moniker ‘Group f.64’ (named for the smallest camera aperture setting, which yields the greatest focus across long distances), they broke away from the soft, painterly aesthetic that dominated art photography, and embraced sharp images.

A group exhibition at the de Young Museum, organized by Adams in December of 1932, popularized their aesthetic. The group didn’t last long, but their legacy did. SFMOMA’s current show, “Around Group f.64: Legacies and Counterhistories in Bay Area Photography,” which closes July 13, revives that history and traces its connection to younger artists.

Janet Delaney, Zig Jackson, Ray Potes and Adrian Martinez, four contemporary photographers whose work follows in the footsteps of Group f.64, and who have work in SFMOMA’s current exhibition, spoke to a packed audience at the museum’s Phyllis Wattis theatre earlier this June.

“Group f.64 was one of the few honest-to-goodness artistic movements to come out of the Bay Area, and perhaps its most famous,” said Erin O’Toole, who led curation of the show.

The exhibition begins with the photographers of Group f.64 and then snakes through the subsequent photographic generations, tracing the development of Bay Area photography.

“The exhibition treats Group f.64 as a sort of nexus,” said O’Toole. “It’s not meant to be a definitive history of Group f.64 by any means, but a selection of interconnected stories.”

Guggenheim fellowship recipients Janet Delaney and Zig Jackson form part of this nexus, as graduates of the San Francisco Art Institute where Ansel Adams helped found the first-ever fine arts photography program in 1945.

Delaney’s first major series, “South of Market 1978-1986,” which is included in SFMOMA’s exhibition, used a large-format camera to document residents of the South of Market neighborhood at a time when large sections of it were being demolished in the name of redevelopment.

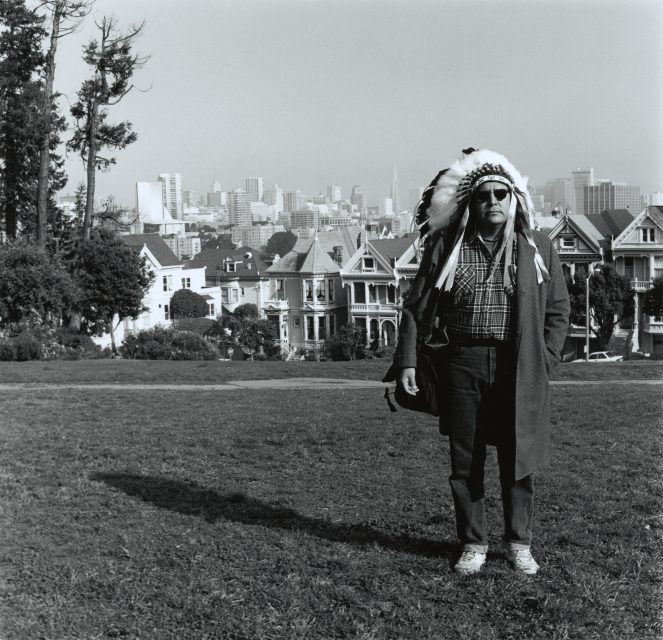

Jackson’s selected series “Indian Man in San Francisco” is made up of pictures of himself wearing a Native American headdress, photographed throughout the 1990s at iconic San Francisco locations.

In their work, both Delaney and Jackson play with the long depth of field that characterized the style of Group f.64. “Many of their concepts were top of mind when I was studying in the 1970s,” Delaney wrote to Mission Local after the talk. “Aesthetics are only one aspect of a successful photograph.”

Delaney wanted her work to be visually engaging, but also politically questioning.

That political questioning runs throughout the exhibition, including in Edward Weston’s portraits of poet and activist Langston Hughes, taken in Carmel, California, and photos documenting depression-era poverty in San Francisco.

“I have left behind, or left out, all the beautiful parts of the city that have already been memorialized in calendars and tabletop books,” wrote Delaney. Forty years after being taken, her photos are a time capsule of a former era and a referent to change that is still happening.

Delaney is working on a follow-up series, titled “SoMa Now,” where she returns to the same neighborhood to track the changes that have occurred since her original series. “Photographs carry the past into the present time,” Delaney said. “By knowing where we were, we can hopefully better understand where we are.”

This collision of past and present is also at play in Jackson’s work. “Indian Man in San Francisco,” he wrote, came out of his desire to show “that the Native American is still here and is still strong, and not forgotten.”

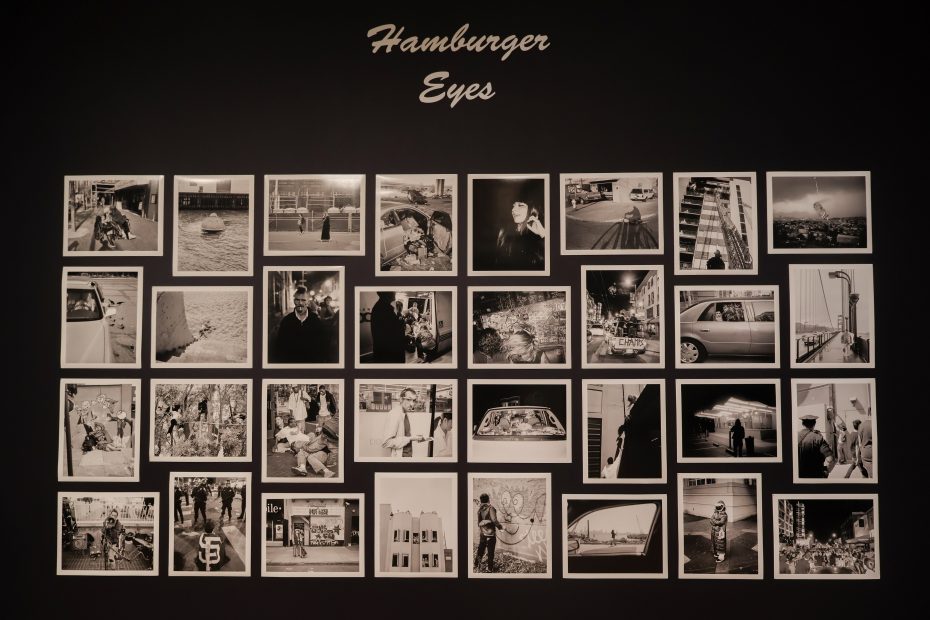

Ray Potes, creator of the local photography magazine Hamburger Eyes, and Adrian Martinez, a photographer and curator at SFMOMA, show work in the final section of ‘Around f.64,’ as representatives of the more recent San Francisco photographic scene.

Hamburger Eyes, based in the Mission, has published more than 7 million photographs from California artists, Martinez’s included.

“It brought so many different people together,” Martinez said of Hamburger Eyes. The zine is an example of the evolution that San Francisco photography continues to undergo.

O’Toole recounted that Potes said, “I’m SO f.64” when asked to be part of the exhibition, despite what might seem like aesthetic differences. For Potes, the legacy of Group f.64 is more about a San Francisco lineage than any specific photo technique.

Potes and Martinez sometimes adopt the techniques of Adams, Weston, and Cunningham, but they also learn from newer developments.

Tracking San Francisco’s photographic evolution through Group f.64, a collective that ended almost 90 years ago, feels at first like a minimization of how much this city has changed. But the photographers highlighted in ‘Around f.64’ show the opposite.

The fact that Group f.64 set out to revolutionize photography is more important than the specific elements of that revolution. There are many links between the eleven trailblazers who started a movement in 1932 and the contemporary photographers who spoke on June 5. That nexus of change, their insistence on developing, is the enduring quality keeping them linked.

The 2022 closure of the San Francisco Art Institute in 2022 can feel like an end to the chapter that linked the contemporary artists with Group f.64. Delaney believes otherwise.

“I’m sure we will continue to share ideas and support one another even without SFAI,” she wrote. “Keep shooting and loving what you do,” wrote Jackson, as advice to young photographers. “Enjoy taking pictures and carry it in a sacred way. Everything will be all right.”

Another discussion of San Francisco photography, including work by Delaney, will be held at the Legion of Honor on Aug. 9 as part of their ‘Closer Look’ series.

There is nothing wrong about recalling times when photographers were often more painstaking and sacrificed dearly to share their own visions. We owe them a lot and are still learning from them.

A comprehensive assessment has yet to be made about how digital cameras revolutionized and democratized photography.

Living in San Francisco and its proximity to the digital revolution has been integral to feeding my own interest in photography.

In the early aughts (before Flickr or Instagram were much), I found a local website that featured scenes of places like Red’s Java House on the Embarcadero. It was intoxicating! Such snaps would previously have ended up in someone’s closet.

I loved what Jef Poskanzer was doing with his digital camera over in Berkeley. He still records his encounters with lunch and other daily adventures. (Now it seems, just about every photographer is doing something similar, but no one, naturally, can do it quite like him.)

There was also the charming Balloon Hats project of Addi Somekh and Charlie Eckert. Before digital, who would bravely travel the world to do anything like what they did– bringing joy to so many in the process?

A little later, I learned what San Francisco native Nancy McGirr was accomplishing with her Fotokids project in the slums of Guatemala. Imagine giving poor children an opportunity to photograph what was important to them in their own lives– and what it would lead to!

Cellphones have accelerated the ability of more people to immortalize their interests and lives, creating a superfluity of images that is a bit overwhelming to say the least. Still, we remain transfixed and fascinated by how even the humblest image has the power to provoke nostalgia, memories and ephemeral feelings.

Great images, marked by their unforgettability and “soul power” typically provoke more.