Not long into his brief, wondrous life as a San Francisco building inspector, Onaje Boone was taken aside by a higher-up. It was, to Boone’s recollection, a strange and terrible discussion.

Boone, 47, a former carpenter, a licensed contractor and a building inspector in both the public and private sector for more than a decade, was told last year that there were issues with his report writing. Specifically: They were too detailed. If the rebar is good, just write, “rebar good.”

This was not the sort of advice Boone expected to receive while being paid six figures to serve as a building inspector in a major city.

“The code calls for so much space, so much cleanliness of the area, a certain type of waterproofing,” he says, going into minute details about lap splicing and other matters of some importance in a town situated between two major earthquake faults.

“I write it specifically to what the code book calls out,” he continues. “Whatever was required was noted. I know how to write a report.”

For Boone, “rebar good” was not good enough. He continued to write reports his way. And do inspections his way: As in, failing people who didn’t meet the code. There were a few.

“What I was doing was the right thing. It was in black and white: It’s not what the plans say. How can my boss get mad at me?” he says, asking a question that’s both rhetorical and not rhetorical.

“I always felt confident. I had the plans there.”

But other people had plans, too. In early April 2025, Boone was summoned to the office of San Francisco’s chief building inspector. Up until the moment he walked in the door, he thought the meeting was to inform him he’d be getting a raise; that’s how off-guard he was. Instead, he was told he was being terminated after some 11 months, just two weeks before his probationary period was set to end, just two weeks before he would have become a fully vested Department of Building Inspection employee.

When he asked for an explanation, Boone recalls being told that he wasn’t owed one. He received a curt severance letter noting that his supervisor, Stephen Kwok, had recommended he be let go and that this recommendation “was based on your inability to perform the duties required at this department and is not a disciplinary release.”

It concluded by wishing him “every success in your future endeavors.”

Boone’s 11-month tenure as a city worker ended strangely. But, truth be told, it started strangely, too. During the interview process he recalls being asked, repeatedly, what he thought about diversity, equity and inclusion.

He smiles. “I mean, what do you want me to say? I like to be included, you know?”

By now, you may know that Boone is a Black man. You can see his picture. There are around 25 or more building inspectors at any time, and Boone, according to the Department of Building Inspection, was the only Black one. There are, incidentally, a similar number of electrical inspectors and plumbing inspectors. The building department confirms that there is presently one Black electrical inspector and one Black plumbing inspector. Boone, again, was the last Black building inspector.

What you can’t see — but what the people asking Boone about DEI could — is his resume. He worked as a building inspector for the Coast Guard. He spent a decade as a special inspector, a private inspector with area-specific construction expertise whose work is required in addition to city inspections. He has more than a dozen certifications, including many from the International Code Council. In short, his qualifications far exceed those of the average-bear building inspector.

Mission Local sent Boone’s resume, without his name, to a half-dozen current and former Building Department employees. To a man, they were impressed; here’s what three had to say:

- “It’s unreal for him to have all this stuff; he blows everyone out of the water.”

- “He demonstrates a lot of the technical knowledge this department sorely needs.”

- “Are those separate people? Is this all just one guy?”

So, was Boone insulted when he was asked, repeatedly, about diversity? Yes. Yes, he was. But he was offered the job. He took it.

Boone, almost immediately after being let go, caught on doing private construction inspections; he’s earning as much, or more, than he did as a city building inspector. He’s doing fine. But he says what he saw on the job here was not fine. It’s the rest of us he’s concerned about.

Onaje Boone knows how to write a report. He also knows what a construction site should look like. He emphasizes that he was not looking to fail people: “If it’s stuff that can be fixed in a few hours, I’ll go away and come back. I try to work with contractors. It’s easy to miss something.”

But it’s also easy to miss everything, especially if there are no ramifications. Boone recalls contractors who’d casually namedrop their ties to his superiors, but clearly “didn’t read the darn plans. They could not find the details on the plans.”

When Boone talked shop with his colleagues, he was disturbed by what he described as a lack of knowledge of “basic elements” of construction. A number of his fellow inspectors did not see what he described as serious flaws, and they then turned around and asked him why he was failing so many inspections.

Despite his qualifications, Boone was never assigned his own district. Rather, he was a “floater,” who served as a substitute inspector. This, he says, should have been a cakewalk assignment. He was, after all, subbing for experienced inspectors who’d presumably kept an eye on the projects he’d be inheriting.

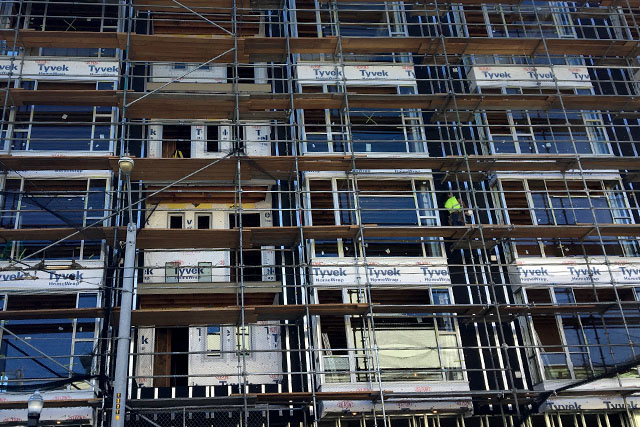

“It was a disaster,” he says. Boone was horrified by the shoddy work he saw, which had been approved, sometimes on multiple occasions. “I was a substitute inspector; that means they got this far!” he says. The problematic construction situations he saw “are not something that just happened. This takes weeks of work to get to. You have to pour concrete, build walls. These things take time.”

Not infrequently, Boone says he saw inspection notes indicating that an inspector shirked an in-person inspection and just had a contractor send him in-progress photos. Mission Local obtained one such report. On the permit tracking system available to the public, it simply says “sheetrock nailing.” But on the internal system, it says “photos for insulation, mechanical and rough frame.”

This indicates that the inspector did not check on any of these elements; instead he ostensibly allowed photos to be taken before those elements were sealed behind the sheetrock. The problem here is evident: The inspector has no idea what’s really behind that sheetrock.

And this, Boone says, happened a lot. “You’d get there, and there’s no history. How can I do a final inspection with no history: No framing, no insulation, no sheetrock?” he asks. “You look at the notes and it says, ‘pre-job walk. OK to take photos of everything.’”

The building department says that “inspectors have the discretion to accept photographs for some minor items identified during an inspection while work is ongoing.” Inspectors we spoke with balked at this: There is nothing in the code, they say, about accepting photos. Building inspectors cannot tell if photos have been doctored. They cannot even tell if the photos provided are necessarily of the work site in question.

After you’ve skipped the insulation, mechanical and rough frame inspections, all that’s left is a final inspection. The only inspection such a job would receive is checking that the screws were properly spaced in the sheetrock. “You’ve missed everything,” says a veteran inspector. “It’s the entire project.”

Whenever Boone asked his coworkers about this, he recalls being told, “Don’t worry.” When he brought it up with his superiors he says he was told “Use your discretion.”

He was already doing that: Boone failed “a lot of Irish guys and Chinese guys. Those are the biggest groups who are most represented at DBI. The ones who seemingly pass the most failable things.”

Boone says he failed contractors despite numerous instances in which he was offered envelopes full of money, sometimes up to $1,000. His colleagues, he says, told him to “wait ’til Chinese New Year.”

None of them, he says “were stupid enough to tell me they took the money.”

Numerous current and former inspectors tell Mission Local it’s not uncommon for builders to offer money, alcohol or gifts to inspectors, especially new inspectors.

“They want to feel you out,” says one veteran former inspector. “And once you’ve taken the money, you’ve sold your soul to rock ‘n’ roll.”

The builders can be very insistent. One longtime inspector said he didn’t even realize that someone had shoved an envelope into his jacket pocket during a site inspection; he had to return and toss it over a gate.

The building department acknowledges it is aware “that illegal overtures are sometimes made to staff.” Inspectors are instructed to inform their supervisors, who can ferry the issue up the chain to senior leadership, which may result in referrals to the city attorney or district attorney.

So, that’s how it’s set up on paper. In the field, inspectors tell me, they are not incentivized to complain to superiors about contractors’ untoward activities, especially when contractors casually namedrop their ties to those superiors.

Boone, for his part, says he never took the money. He countered offers by asking builders to, instead, phone his supervisor and say he was doing a good job.

“I should’ve asked them to send an email,” he says with a wan smile. “Then there’d be a written record.”

There are a lot of Irish people at DBI, a lot of Chinese people, and an increasing number of Latinx people. Boone, clearly, was not on any “team,” but this was the case both physically and metaphysically.

During meetings, he says, inspectors were told to keep things moving, don’t slow down construction and don’t stop it. Boone understood what was being asked of him. He couldn’t help but notice that he wasn’t being told “make sure things are being done right” or “make sure they’re doing construction correctly” or even “make sure they are following the plans.”

So he used his discretion. And now he’s not on the team.

There’s not much he can do about it. Probationary employees are vulnerable, and Boone’s union says it is essentially powerless here. “I feel this was unjust,” Boone says. “But people don’t really care about justice. So I’m letting it go.”

Boone says he earned two more certifications while serving as a San Francisco building inspector. He’s taking his talents elsewhere. He’ll be fine.

He wishes San Francisco every success in its future endeavors.

Stephen Kwok – built an illegal ADU on his own property and hid from reporters.

missionlocal.org/2021/08/dbi-adu-san-francisco/

This is why Boone was fired – because Kwok is just another face of corruption at DBI.

The mindless mouths inventing trash talk about Boone in comments here need to get a clue and at least read a little bit before they invent their narratives from whole cloth.

So glad you called this out.

The last “black” building inspector in San Francisco, or the last honest one?

If one lives in a compromised building in San Francisco is it worthwhile to complain?

I think the title is a reference to the movie “The Last Black Man In San Francisco”

No matter how benign the comment, someone will dislike it

Well, this *is* San Francisco

SFDBI is set up to get their revenue from permit fees. The more projects they can approve with the least labor, the more the department makes. No surprise there’s corruption. And I’ve not seen a mayor yet who’s willing to take it on.

I was bummed to see this aricle. Boone actually inspected my propert recently (builder owner). Failed me first time but gave very detailed instruction what to follow up with. Nothing but respect for guy, he was polite, took time and provided guidance what, why. Not sure whats story but defintely wish more inspectors are like him. Kind off off putting they are bringing DEI into convo given he is clearly qualified, and probably had harder time making it into DBI.

Thanks for covering this story. It’s very concerning to learn of corners being cut. This situation warrants more investigation. I want more buildings and housing, but not shoddy construction. Construction workers can make mistakes; they aren’t engineers and their flexibility isn’t always functional.

Thanks for reporting on these kinds of stories, Joe.

I am glad Boone was able to talk on the record and I wish he would sue the city.

Disappointed the DBI is still corrupt to this level. Scares me about the health, safety and welfare of our current citizens when we are allowing unsafe construction to pass through.

Maybe you know Inspector Boone? The man has more certifications than most inspectors at the entire department. Competency and success comes with mentoring and support, neither of which was he afforded by the management team at DBI. And that he was the only black man in the Building inspection group more than likely played a significant role in him being laid off. Please take note that the groups with lots of support within BID are likely to pass probation. And as the article notes there are no other black building inspectors. Is this happen stance? Likely not…too many inspectors from one small island in the Atlantic working as inspectors to convince anyone of that….

For anyone who has dealt with DBI, it’s obvious Boone is way too qualified and upstanding of an individual to last. DBI is run my a bunch of uneducated, corrupt clowns who know little about proper building. Big mistakes happen all the time.

https://missionlocal.org/2021/06/gas-line-retrofit-hearing-seismic/#:~:text=On%20April%2021%2C%20we%20published,city's%20own%20chief%20plumbing%20inspector.

The plan seems to be to let the problems fester for years and then jump up and “discover” hundreds or buildings were not properly built decades ago, Force the owners to pay for costly inspections and repairs now. Who was running planning and DBI back in the 1970s and 80s?

Mr. Boone sounds like an honest, intelligent inspector. He and his high morals, and work ethics need to be admired, not punished.

What is wrong with San Francisco to allow this to happen?

When I worked at SFDPW the pattern was the same. I was harassed, passed over for promotion, and eventually fired when I exposed department corruption as soon as I found out about it. I was the most qualified employee among the ranks, more qualified than some of management, and did management level work but was the lowest paid employee in the department. My union did nothing to support me, in spite of the whole hiring process being a violation of the contract and city laws.

Great story! This guy sounds like a very upstanding & ethical man who maybe would not “go with the program”. Unlike maybe Bernie Curran???? I don’t trust any building inspectors who work for San Francisco.

Not all that surprised he was let go honestly.

If you’re under a lot more pressure to push through more projects then it’s pretty clear you are going to let go of anyone in a probationary period who seems to be blocking that kind of progress.

Diversity at DBI translates as “ Are you from Cork or Donegal?”

He is the best in knowledge and experience amongst ALL. Its like someone told you he never lies. THATS A LIE?

Need to hear more about the other side of the story…

DBI says you aren’t owed that basically, if you read the article. You’re not going to catch them talking to reporters about corruption in the department on the record. What exactly are you thinking they’re going to say that we don’t already know?

With the very limited info and lack of context in this article, this is a “he said/she said”. There’s a strong temptation to interpret it through the lens of your already-existing beliefs. I’d implore everyone to keep an open mind and hold their certainty in check.

Hey K. Maybe he is the victim of a vast DBI conspiracy. Maybe he has a case. I’m sure if I had a wrongful termination case the first thing I would do would be to talk to an employment attorney. I’m sure when that attorney told me I had no case I would go to the DBI’s number one adversary and tell them a fabulous story about corruption and racism that led to my termination. There’s just one difference between you and I, I think his story is suspect. He’s a tremendous victim. You keep on keeping on K.

Gigi —

Mr. Boone did not come to me. I sought out Mr. Boone. Don’t forget, ma’am: “When you assume, you make an ass out of u and me.”

You should be more careful making false accusations in writing.

JE

Gigi – your replies sound suspicious. Sounds like you’re the supervisor that terminated him…trolling here. LOL

I’m an architect and I follow the SF Building Department (DBI) closely as it affects me greatly.

The DBI is and should be under pressure to not be a roadblock to construction. Of course they should be thorough to assure buildings are safe. But construction is not a science and every project has special circumstances that cannot be identified in advance. Contractors need flexibility to provide alternative solutions if the one on the plans doesn’t work.

This inspector would stop the entire construction process and force the design team to start all over in the approval process to make a benign plan modification. It’s absurd. While I have not heard of him inspecting any of my projects, his “by the book” methodology just doesn’t work in construction. He would have caused millions of dollars in increased costs in a city that can’t afford to have higher housing costs. Inspectors must be FLEXIBLE and safe. The article clearly states he was not. He was better at creating more unnecessary bureaucracy.

Add to that his race, which he doesn’t even say was a factor, but the author here decided to whip out the race card for him.

Finally, while I’ve heard rumors of Chinese inspectors taking bribes, mostly years ago, in my 31 years designing in SF, I’ve never ever experienced or even heard of any of my contractors engaging in bribery.

It was best he was terminated.

Typical contractor logic, inspections aren’t necessary even when the work is shoddy enough to fail. If you deviate from the plans without documentation there’s no actual way you’re doing the job correctly even if the end result is “ok” – and the inspectors JOB is to find out when you’ve deviated and give you a chance to fix it, or fail you. That’s literally what they are supposed to do and here you are saying the opposite. If they’re far enough out of code that he’s failing sites, that’s a good thing. That’s why we pay him 6 figures and don’t allow them to take envelopes full of cash on your “good word” as a contractor that it’s all safe. I’ve overseen planning for big projects in SF and as the Bay Bridge rod fiasco and sinking towers and fall-down-hill sh!t shows demonstrate, doing things wrong has consequences. No, they’re red tagging you because you failed, not because the inspector failed. Best case scenario you fix it, worst case scenario you start over. That’s life, that’s on you. Do it right or go somewhere they don’t check.

There is a dearth of Black representation both at DBI and in the SF trade scene generally speaking. It would be remiss to leave race out of the equation in this instance.

So the percentage of people in any and every job in the city should exactly mirror the demographic breakdown of that city?

Says who?

I don’t care to have a DEI argument. I’m pointing out what is, and the more interesting question to me than the one you’ve presented is why it is.

DBI is somewhat representational of a bygone era. Whites, Chinese, and Irish built San Francisco. The roads, the mechanical infrastructure, the buildings… built that shit.

Blacks and Latinos came later, filled industrial jobs and carved out niches in other lines of work.

Look at today’s ‘Day 71 16th Street Crackdown’ article and take note of the four DPW workers cleaning the alley. Notice anything? Niche.

Shocking! The inspector who didn’t pass his probation is disgruntled. If he’s so honest how come all these contractors who tried to bribe him, a felony, haven’t been prosecuted? How come all the other building inspectors who told him to ignore code violations still have their jobs? Surely this pillar of honesty reported these crimes and misdemeanors to the authorities. How come the black electrical and plumbing inspectors passed their probation? Is it because they’re black or because they’re competent?

If you read the article he wasn’t given a reason for termination, but the implication is that he did his job properly and the (corrupt) dept. heads didn’t want him getting in the way of them passing shoddy developer work for their buddies. Nothing about his tone in the article says “disgruntled” at all, he says it was an unjust firing and from what we know he’s probably 100% right about that. ” How come all the other building inspectors who told him to ignore code violations still have their jobs?” – Because the pressure to pass the shoddy work comes from the top, obviously, duh. Read harder. ” Surely this pillar of honesty reported these crimes and misdemeanors to the authorities. ” – Now we know you didn’t read it. Now you’re going off into race-talk and pretending he was incompetent in the same breath, based on nothing. Gee, glad you’re not HR at my dept…

You must be new to SF because corruption runs deep in all these departments. Or maybe you don’t read the news?

This is laughably naive and you clearly do not understand anything about the BS that goes on in the local govt.

Let’s see if I understand this:

This guy was hired on a probationary basis. He was told to write his reports differently (perhaps because they would be easier for others to read?) He refused. So he was let go.

And you think this is a problem because he’s black?

Why should being black allow him to refuse to follow directions from his supervisors?

He sounds like a problem employee who we are better off without. Who needs a soliloquy on rebar?

At the salary he was being paid, we can get someone to write more concisely.

You don’t understand employment basics. Probation is your first year (or x months), everyone goes through it. It’s called the probationary period, it’s not for bad conduct. He was told to skimp on his job and refused, was invited to take bribes and refused. They fired him without giving him a reason and abused the probation period timing to get him out before it would require CAUSE, which is a legal requirement for termination after the initial probation period. It’s clear why – Kwok wants to maintain the culture of corruption at DBI with friendly contractors he’s known for years and apparently thinks he owes favors to. You sound like a problem reader, not an employee of anything that requires the skill.

Keep typing, Kurt! Don’t ignore a single comment. Last word? Best word! Your word, of course.

I replied to 3 comments, once each. If you have a problem with what I said go ahead and point it out. What do you have to say for yourself?

With the salary he was being paid, he was actually doing the work of the people. Not incentivized developers or design professionals. The plans are there for reason and if you don’t follow them, then maybe you need a soliloquy to help you better understand what is required.

Are you serious? His primary job is to follow the code of conduct / laws of his job. He’s a city worker. It’s not just what his (corrupt) supervisors tell him to do. Are you missing the point of the article? He’s not a sheep going along with the game … he’s thinking and doing for himself and committed to ethics.