Mission Local is publishing campaign dispatches for each of the major contenders in the mayor’s race, alternating among candidates weekly until November. This week: Ahsha Safaí. Read earlier dispatches here.

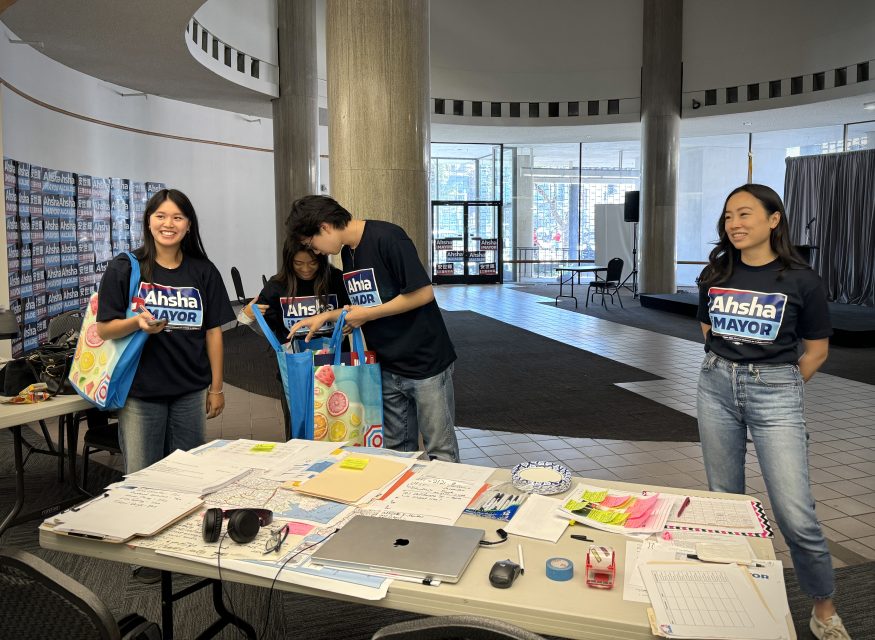

At 4 p.m. on Tuesday, seven campaign staffers for Ahsha Safaí were getting ready for some door-knocking at their 22nd and Mission headquarters.

“Ahsha for Mayor” T-shirts were neatly folded on the table, waiting for volunteers to take home. Later, the campaign staffers would all change into one before they broke into four groups and headed to two precincts in the Mission, carrying light-blue tote bags in fruit-and-beach prints, and window signs and door hangers.

“You each grab an adult,” Tomas Gonzalez, the campaign field manager said to the four college-aged staffers, asking them to pair up with a more experienced campaigner.

The walls of the headquarters were festooned with maps of the city’s 11 supervisorial districts. Precincts were denoted by pink post-its and filled by color markers, indicating where the campaign has covered.

Staffers asked this reporter not to take photos of the markings, so as to not give away to campaign opponents where the team has canvassed and where it has not.

Races can get very competitive, explains Lauren Chung, Safaí’s campaign manager, who is now on her third tour of duty with Safaí on the campaign trail. When others know where the campaign has been, they deliberately go to the same spot and disperse their campaign materials.

The competition was evident on Tuesday afternoon. On one block, Mark Farrell signs hung in at least four windows. “There must be a house party for him here,” said Safaí.

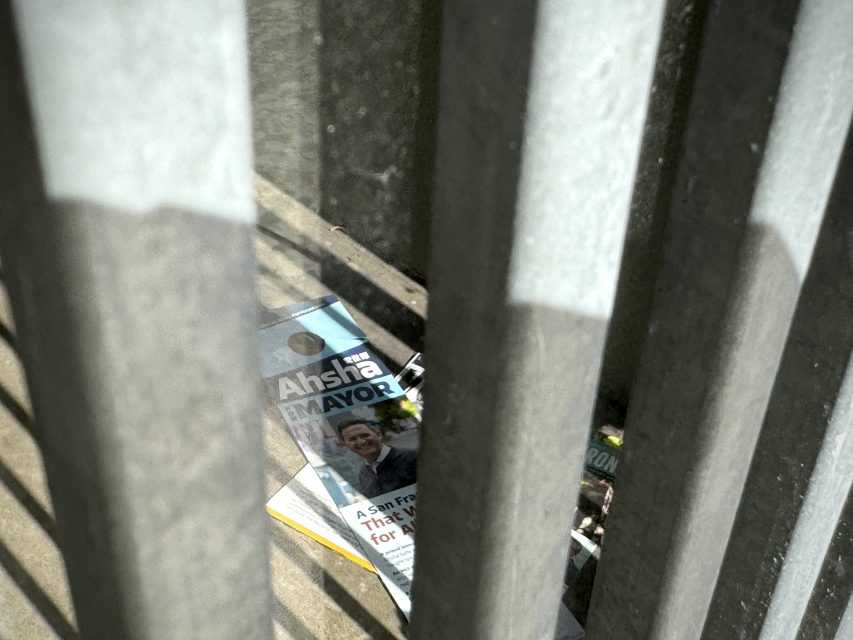

Seeing a flier from Safaí’s competitor Aaron Peskin through the gate at an apartment on 24th Street, Chung said, “well, I have to put one in there.” She skillfully slid a door hanger through the gate. It dropped just at the right spot, covering Peskin’s flier.

They were not just knocking on any doors. Jackie, a 19-year-old who was on her first door-knocking assignment since joining on Saturday, held her phone the whole time with a commonly used political canvassing app called PDI (Political Data Intelligence).

With the software, the campaign could pick which group of voters to target; Chung referred to each category as a “universe.” The addresses were marked in green dots — these are “high-propensity voters” who have consistently voted in past elections.

Intuitively, campaigns target voters more likely to vote early, and then come around to less likely voters later, Chung said, because “you only have so much resources and time.”

“They are people who pay attention early,” Chung said. “They open the doors and they want to have conversations.”

The door-knocking on Tuesday, not surprisingly, was more than knocking the door itself. There was the long silence after ringing a doorbell, the occasional dog barking, and figuring out where to put a door hanger when a doorknob is nonexistent.

When residents opened the door — for one of the teams, about 15 did on Tuesday — most said they haven’t made up their minds yet. They thanked Chung and Jackie for the campaign literature and said they would need to “sit down and dig in” more to make a decision.

But some of them have decided. They are highly engaged voters, after all.

“I’m going with London Breed, reluctantly,” one resident said.

Chung, catching the caveat, asked, “Why reluctantly?”

“I can’t get with the drug testing and the aggressive homeless sweeps,” she said. “But I just don’t know if Ahsha is radical enough for me either.”

No matter, Chung reminded her that Safaí was against Prop. F in March, which required recipients of some monetary city benefits to go through drug screening. He also opposed Prop. E, which reduced police oversight and allowed police vehicle chases for “violent misdemeanors.”

If a resident was adamant that they knew who they’d vote for, Chung made sure to ask them to consider voting for Safaí as the No. 2 choice on the ballot.

There wasn’t too much talk about the policies, at least when the campaign team was doing it. They touched on big issues like public safety, street cleaning and homelessness, but did not not drill down into the specifics. It may be hard to do so when standing in someone’s doorway or garage.

“I think when it’s about the mayor, it’s more about the large scope of things,” said Chung, who worked on Safaí’s supervisor campaigns and served as a legislative aide previously. “But when it’s the supervisor, people are like, ‘Can you fix that thing right there?’ They really rely on you.”

Nonetheless, when Safaí joined around 5:30 p.m. after the Board of Supervisors meeting, he did spend more time talking with each person who opened the door for him, telling them about his track record and asking how long they’ve lived in the city. He responded accordingly when they brought up their concerns.

When cyclists complained about the Valencia bike lane, he told them he was the first to send a letter to the SFMTA requesting it be reverted to the original side-of-the-road design. When people criticized his opponent Farrell’s plan to bring cars back to Market Street, he reassured them he would 100 percent keep it car-free, and added that he also supports shutting down the Great Highway.

And when a neighbor, an electrician, said he was a member of IBEW 1245, all Safaí had to do was to tell him he worked for the janitors union for almost a decade.

“Can I count on your vote?” Safaí always asked at the end of a good conversation. A few of them said yes, and to Safaí, that was a win.